|

|

Coastal and subcoastal non-floodplain rock lakeCoastal and subcoastal non-floodplain rock lake – Hydrology Click on elements of the model or select from the tabs below

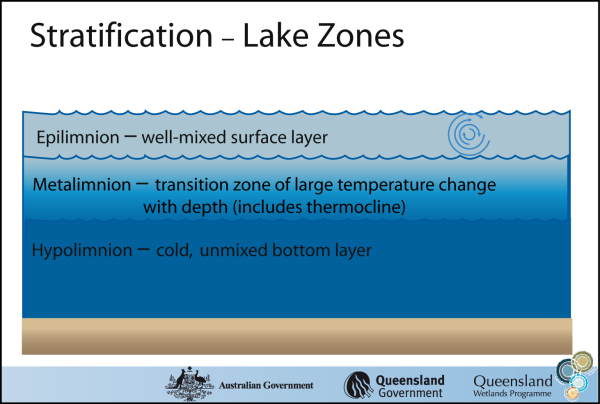

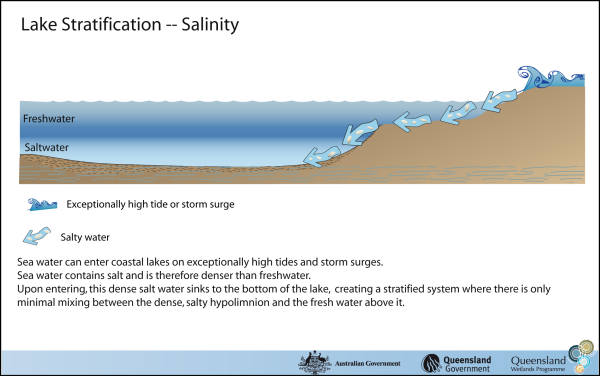

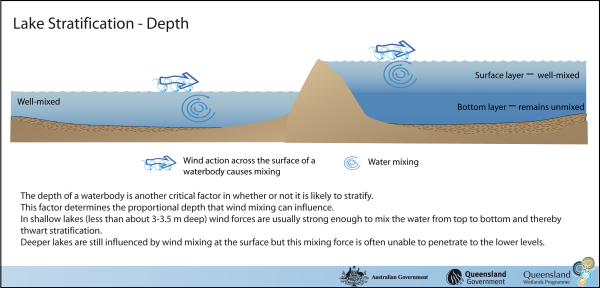

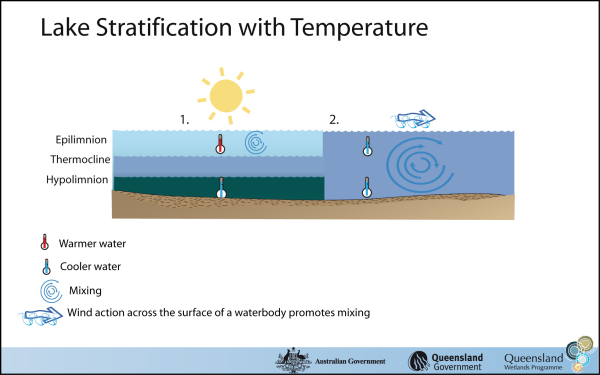

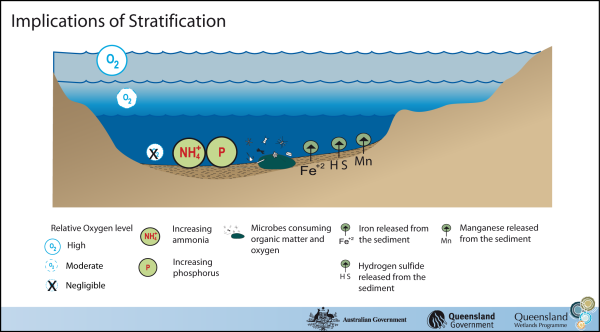

Non-floodplain lake hydrology is related to a site’s topography, substrate type and position within the catchment. Climatic factors (especially those related to rainfall) also play a significant role in the regularity, seasonality, duration and amount of water entering and leaving the wetland. Rock lake hydrologyGenerally water in crater lakes is fed from rainfall, and run-off from the local watershed or catchment within the crater rim (if it is a crater lake) or from underground springs. Deeper rock lakes, or those with constant groundwater supply, can remain wet. Only a few are seasonal or intermittent lakes with a palustrine (swamp) component. They range in size from small ponds of less than 1 ha to larger lakes of over 100 ha. Water inputsNon-floodplain wetlands can be flushed with rain, run-off from the local watershed and from groundwater discharge, or a combination of these sources. If groundwater table levels and substrate permeability permit, this can lead to more constant systems. This wetland habitat type can play a role in groundwater recharge/discharge. An important point to note is that groundwater flow tends to be clear (not turbid), compared to surface water flow. Water outputsEvaporation, transpiration and groundwater recharge can lead these systems to dry out, often completely. Water may also flow out to the ocean via distributary channels, depending on topography. Stratification     Stratification is driven by density differences within the one waterbody. Temperature has a significant effect on water density—warmer water is less dense and therefore will float on top of colder water (of the same salinity). 1. Sunlight warms the upper surface of the lake (the epilimnion), making it less dense than the water below, allowing it to float and discouraging mixing (hence inducing stratification). Only a small temperature difference is required to prevent mixing between layers, depending on the lake’s surface area, shape and wind fetch. 2. The stratification can break down through a decrease in surface temperature from cooler air temperatures that occur either at night time or seasonally, depending on the lake’s climate and other characteristics. The decreasing density of the cooling surface water, along with wind action, causes this surface water to sink and mix with the deeper water. During this time period, most of the lake water is at the same temperature, and surface and bottom waters can mix freely. MixingStratified lakes allow very little mixing between the lake surface and the lake depths, virtually cutting off the oxygen supply to the unmixed bottom layer (the hypolimnion). When there is little oxygen input from submerged plants (due to low light levels, for example) or when a large amount of organic matter has stimulated the growth of oxygen-consuming bacteria, the water in the unmixed bottom layer (hypolimnion) can become extremely low in oxygen (anoxic) over time. Anoxia has a range of impacts. Not only does it make conditions harder for organisms that require oxygen for respiration to survive, it impacts on a range of chemical processes. Anoxia and nutrientsIn anoxic conditions, the nutrients phosphorus and nitrogen (in the form of ammonia) become more soluble (dissolvable) and are released from the bottom sediments into the water column. Ammonia cannot be converted to nitrate without oxygen and will therefore accumulate in anoxic water, especially under high pH (basic/alkaline) conditions. During the summer, stratified lakes can sometimes partially mix (such as with the passing of a cold front accompanied by strong winds and cold rains), allowing some of these nutrients to ‘escape’ up into the well-mixed surface waters and stimulate an algal bloom if light and temperature conditions permit. Ammonia can also directly affect animals, such as fish, that are sensitive to ammonia and are repelled by high levels in the water. Anoxia and other trace elementsSome metals and other elements—notably iron, manganese and sulfur (as hydrogen sulfide)—also become increasingly soluble under anoxic conditions and are released from the bottom sediments, especially under acidic conditions. These compounds cause taste and odour problems—a potentially serious concern in drinking water supply reservoirs. Additionally, high hydrogen sulfide concentrations can be lethal to many game fish as well as some zooplankton (microscopic animals that are an important fish food). Hyporheic flowWater flowing through a river can move through the sediments beneath and adjacent to the channel. This is termed the hyporheic zone, where surface water and groundwater mix. The water that flows through this zone is termed hyporheic flow, subsurface flow or base flow, and can be an important source of water for floodplain lakes and swamps. Due to filtering by alluvial sediments (e.g. sand) hyporheic flow tends to be less turbid (clearer) than surface water flow. Stratification zonesUnder certain conditions related to temperature, wind mixing, salinity, waterbody depth and vegetation cover, Queensland lakes can stratify into different layers. The upper layer of a waterbody is a warmer (and therefore lighter), well-mixed zone called the epilimnion. Below this is a transitional zone called the metalimnion, where temperatures rapidly change with depth. The thermocline is a horizontal plane within the metalimnion at the zone of greatest water temperature change. The metalimnion is very resistant to wind mixing. Beneath the metalimnion, and extending to the lake bottom, is the colder, heavier, darker and relatively undisturbed hypolimnion. More hydrology information is available in the chronology of a flooding lake. Last updated: 22 March 2013 This page should be cited as: Department of Environment, Science and Innovation, Queensland (2013) Coastal and subcoastal non-floodplain rock lake – Hydrology, WetlandInfo website, accessed 8 May 2025. Available at: https://wetlandinfo.des.qld.gov.au/wetlands/ecology/aquatic-ecosystems-natural/lacustrine/non-floodplain-rock-lake/hydrology.html |

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation