|

|

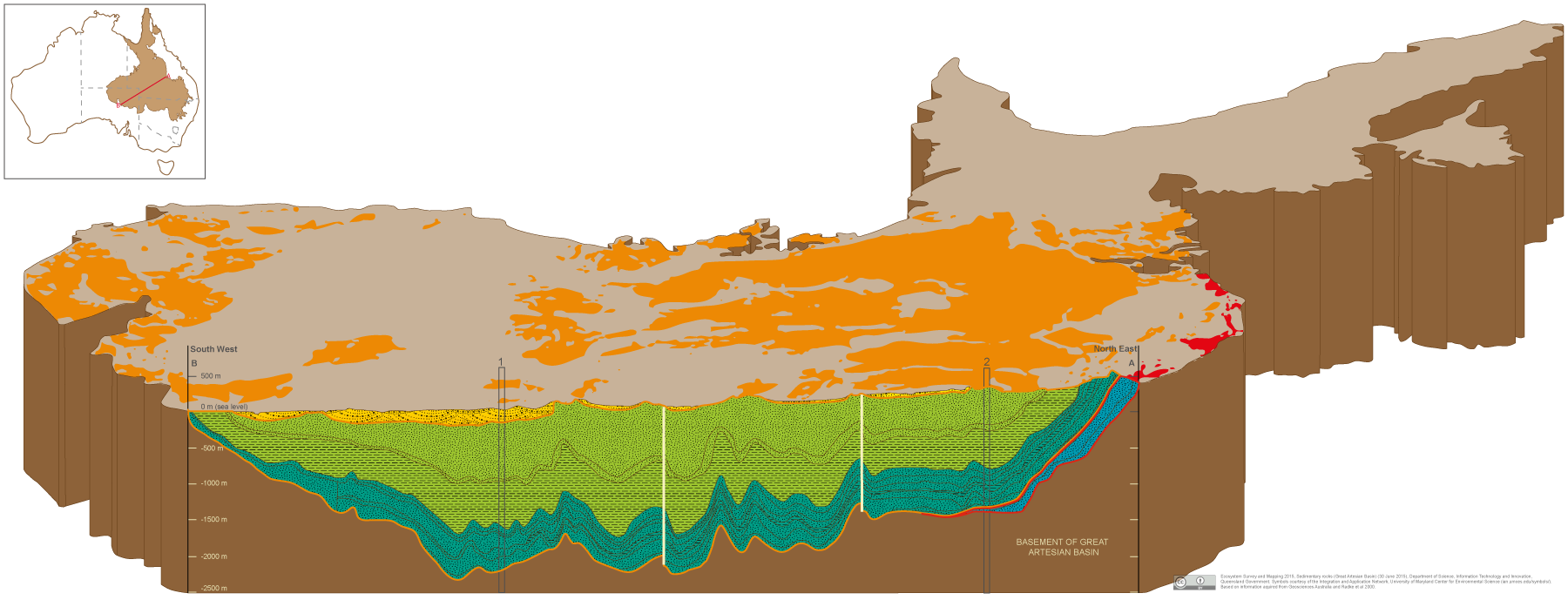

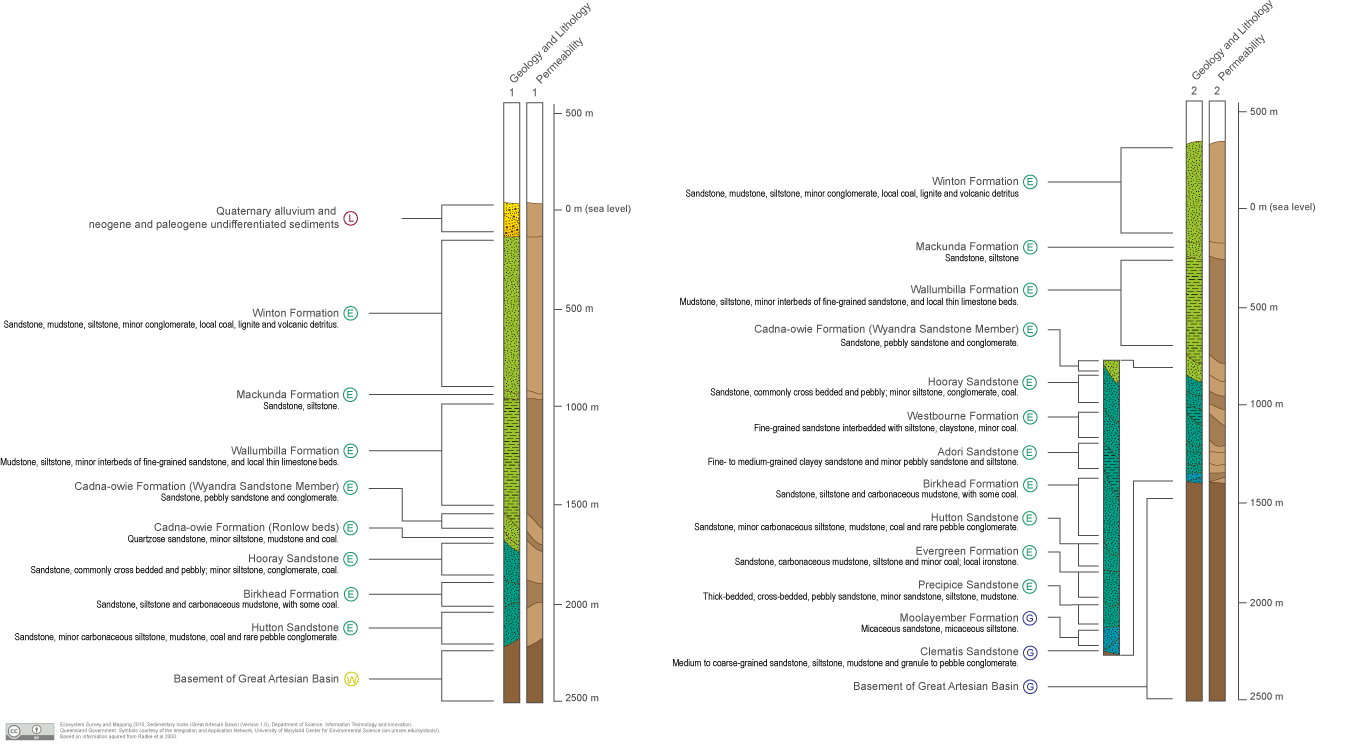

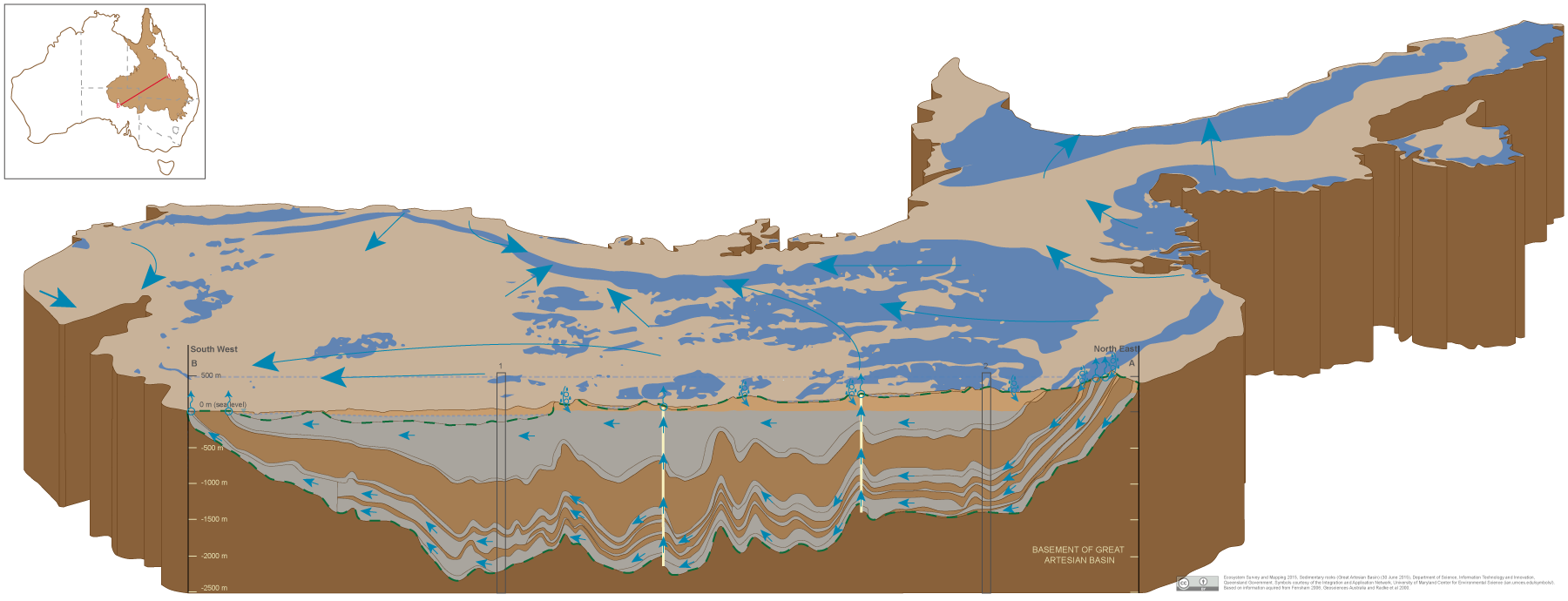

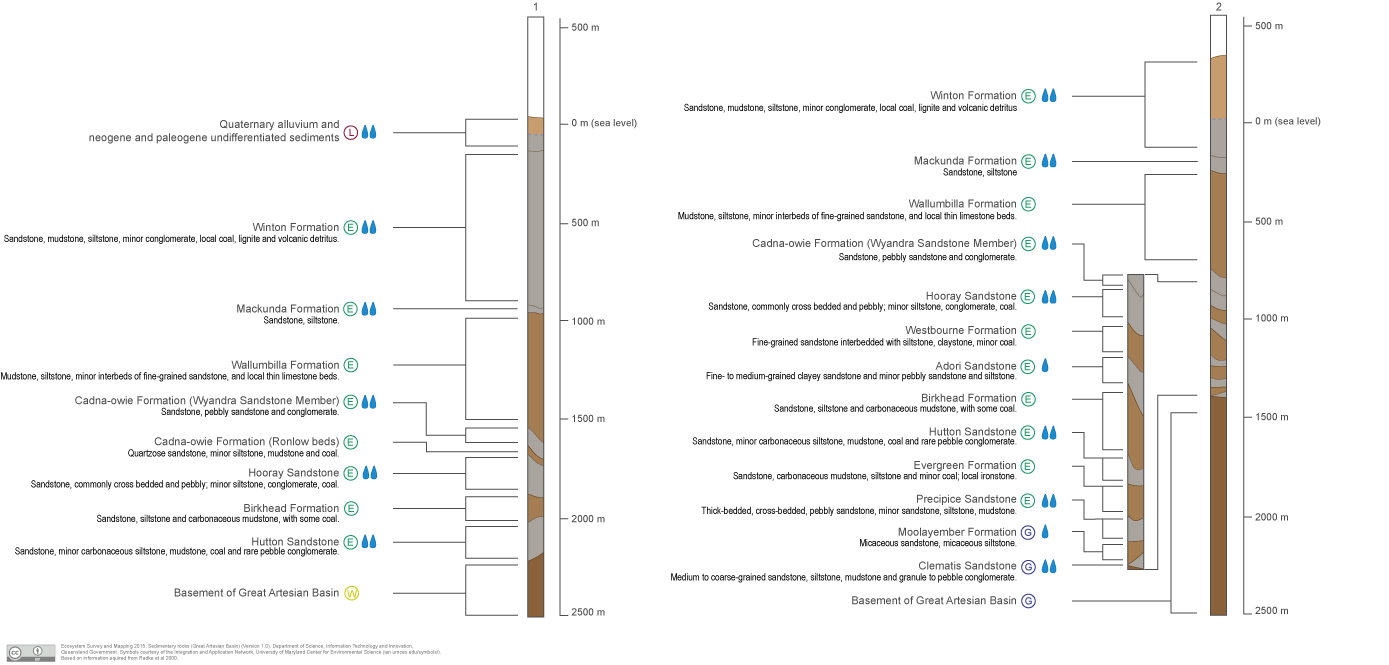

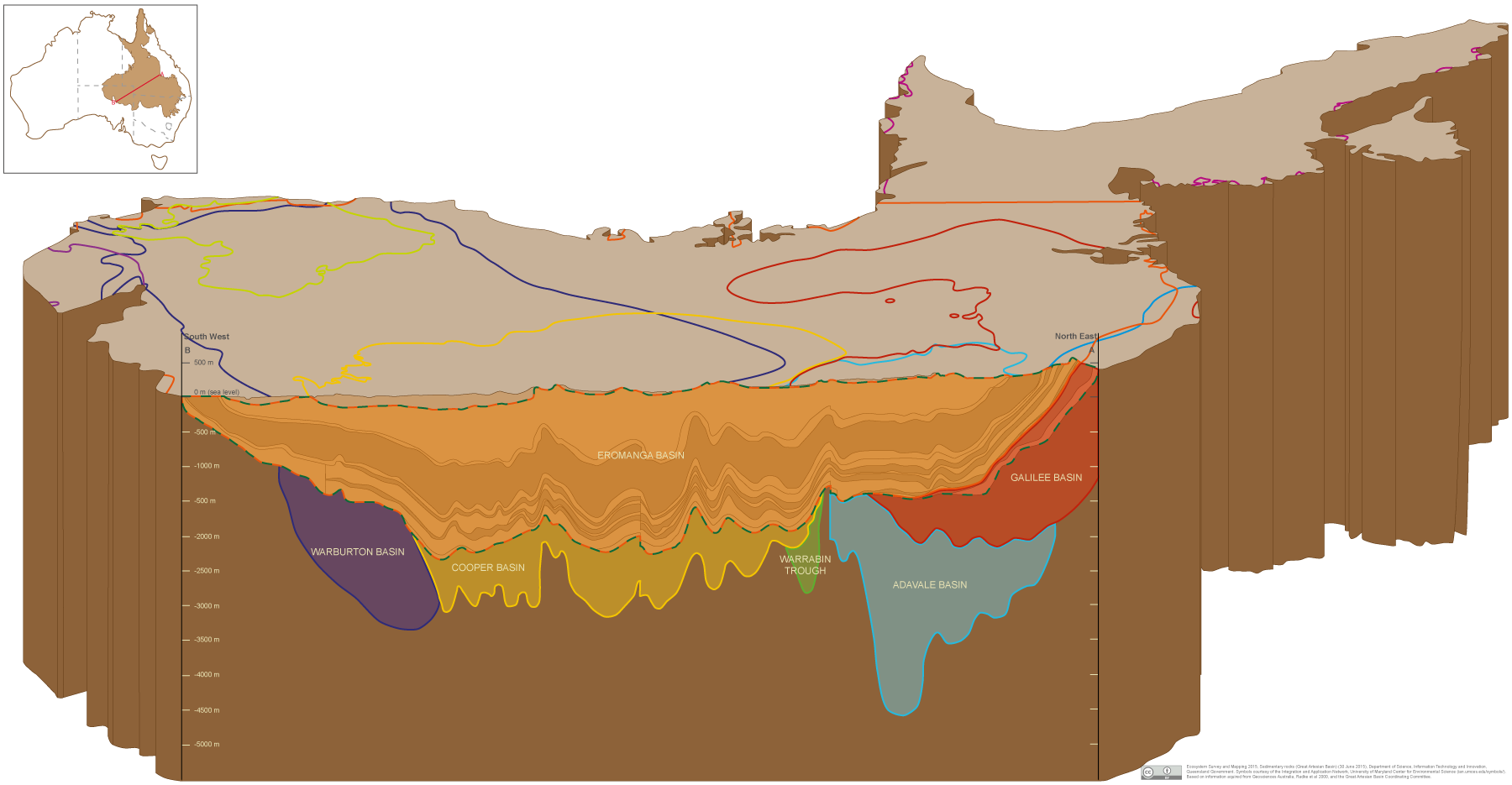

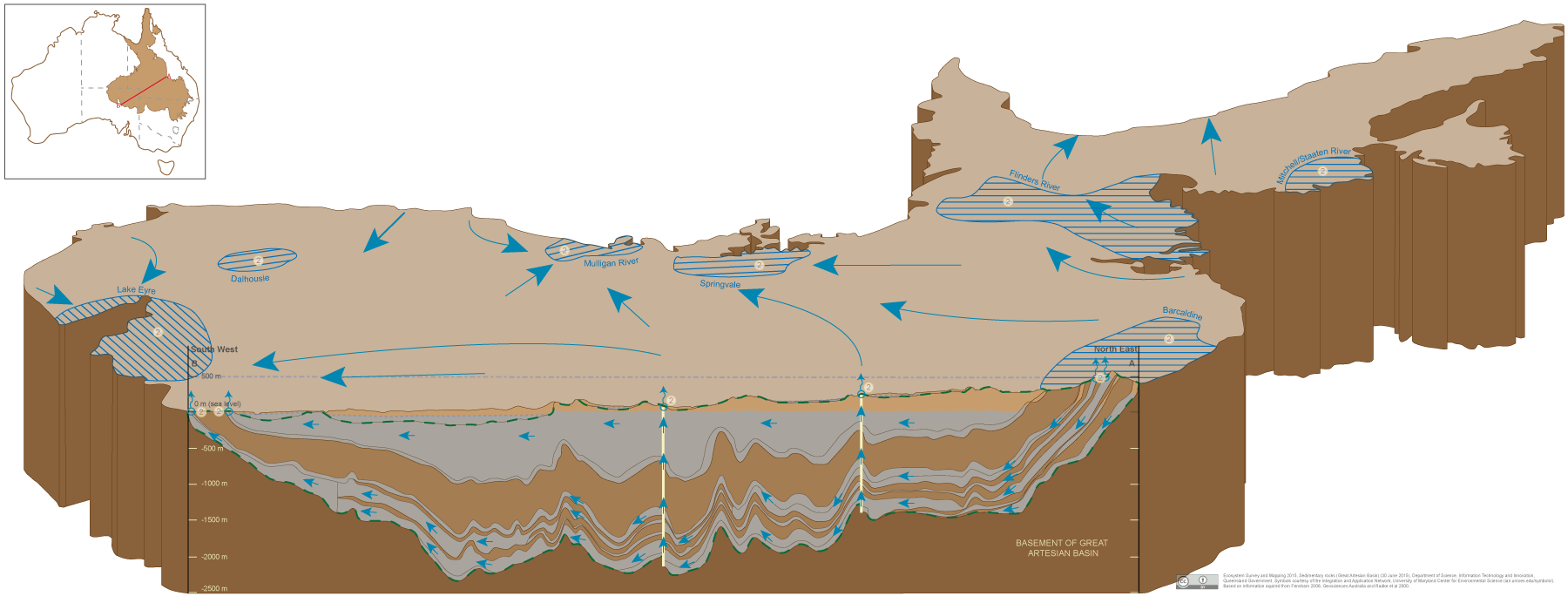

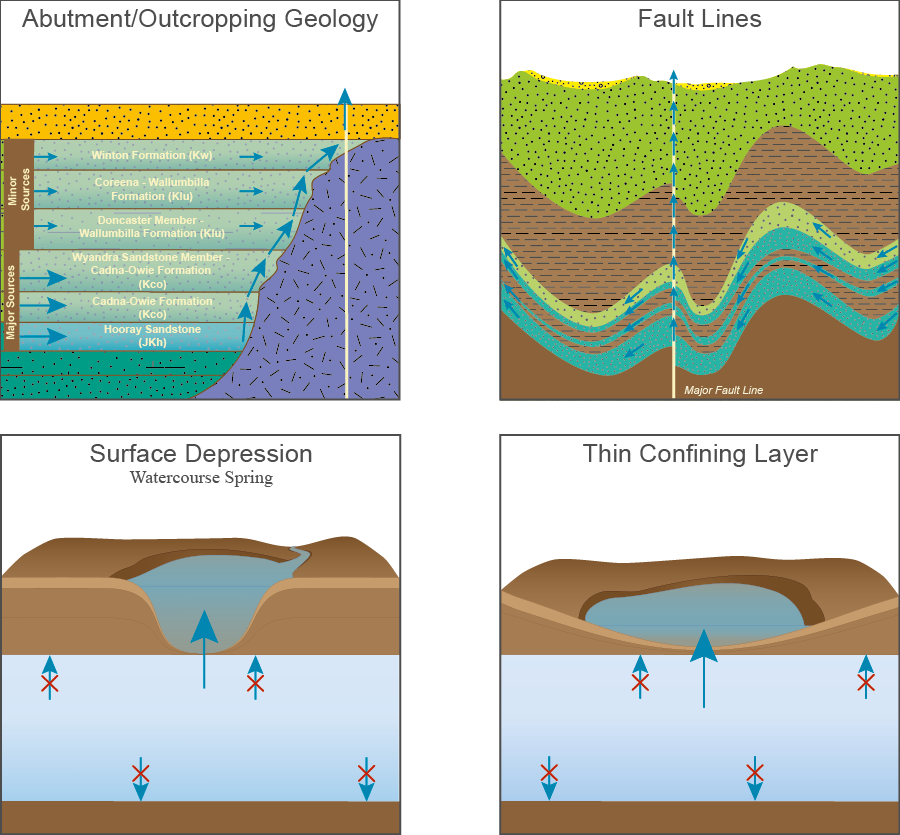

Sedimentary rocks (Great Artesian Basin)Sedimentary rocks (Great Artesian Basin) – Springs and Spring EcosystemsClick on elements of the model or select from the tabs below The following information is correct as of 2006. Newer information on springs and spring ecosystems including GAB springs is available. What are springs?See FAQ page for general definition and information. What are mound springs?While the term mound springs is often used to describe GAB springs[4], mound springs is a loose definition encompassing a subset of all springs (GAB and non-GAB springs) which have the distinctive mound form. Several processes may contribute to the development of mound springs:

Why do springs need protection? Springs have significant environmental, economic and social values. In the Queensland GAB, the number of active springs has declined by almost 40 percent since 1900. This has had a significant impact on land quality, production values and the unique plants and animals that inhabit these wetlands. Some of these plants and animals may not be found anywhere else in Australia or the world and may be protected under legislation. Springs are the subject of some legislative protection in Queensland including under the:

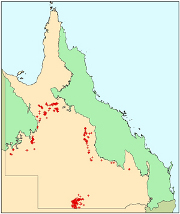

Some species that occur in springs and the spring community itself are also listed under the Commonwealth legislation Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC). Information on this legislation and the species and communities it seeks to protect can be accessed at www.ea.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/index.html Queensland Springs—distribution and assessmentThe Queensland Springs database presents data from a survey of springs conducted between 1995 and 2002 for some areas of the Great Artesian Basin in Queensland (excluding Cape York Peninsula). It also includes data from other areas that is substantially incomplete. The database includes the locations of springs and their flow status (active or inactive). The presence of plant species listed as rare, vulnerable or endangered under the Nature Conservation and Other Legislation Amendment Regulation (No. 1) 2000 is also included. Spring wetlands in seasonally arid QueenslandSeven springs in seasonally arid Queensland, including those outside the Great Artesian Basin, were listed as distinct regional ecosystems by Sattler and Williams[7] (1.10.6; 2.10.8; 4.3.22; 5.3.23; 6.3.23; 10.10.6; 11.3.22). Fensham, Fairfax and Sharpe[3] investigated the floristic variation within the spring wetlands of seasonally arid Queensland, using survey information from both Great Artesian Basin springs and permanent springs associated with other aquifers. It indicated that the regional ecosystem framework provides a satisfactory means of classifying springs. The study indicated that the flora of springs of the Great Artesian Basin aquifers are distinct from other springs in seasonally arid Queensland, but that all have substantial conservation values. The value of the springs as cultural sites, particularly for aboriginal communities, is also very high. In September 2003, an additional seven regional ecosystems (1.11.5; 2.3.39; 6.7.18; 9.8.8; 9.10.2; 10.3.31; 11.10.14) were recognised and included in the Vegetation Management Act 1999 regulation, and are described in the Regional Ecosystem Description Database. Ecological value and conservation issues for the Great Artesian Basin springsThe springs of the Great Artesian Basin provide habitat for a number of endemic plants, as well as fish, snails and other invertebrates[5]. Fensham and Fairfax[1] described results from a comprehensive ground survey of the spring wetlands associated with the Great Artesian Basin in Queensland. That study confirmed and extended previous findings from South Australia[6] regarding the significance of the biological values of the springs emanating from the Great Artesian Basin. The conservation values of Great Artesian Basin springs have been ranked on the basis of their endemic plant populations and the habitat they provide for isolated populations of plant species[2]. The water pressure in the Great Artesian Basin has declined substantially because of the extraction of water from bores, putting the long-term sustainability of the resource at risk. This has serious implications for both the agricultural and mining sectors that use the Great Artesian Basin. A large amount of public money is being spent on rehabilitating bores with the aim of restoring aquifer pressure. Spring flows have also declined, particularly in discharge areas, and preservation of their natural values is highlighted as an important justification for the rehabilitation program (Great Artesian Basin Consultative Council 2000). What are current threats to Great Artesian Basin spring wetlands?The current threats are:

Key recommendationsKey recommendations are as follows:

What can be done to protect the spring wetlands?For more information, download the spring wetlands management profile or the Great Artesian Basin resource operations plan. Queensland Springs Database Please contact us by email: Queensland.Herbarium♲science.dsitia.qld.gov.au References

Last updated: 19 May 2015 This page should be cited as: Queensland Government, Queensland (2015) Sedimentary rocks (Great Artesian Basin) – Springs and Spring Ecosystems, WetlandInfo website, accessed 8 May 2025. Available at: https://wetlandinfo.des.qld.gov.au/wetlands/ecology/aquatic-ecosystems-natural/groundwater-dependent/sedimentary-rocks-great-artesian-basin/springs.html |

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation