|

|

Upper Brisbane Catchment StoryThe catchment stories use real maps that can be interrogated, zoomed in and moved to explore the area in more detail. They take users through multiple maps, images and videos to provide engaging, in-depth information. Quick facts

Quick linksTranscriptThis Map Journal is part of a series prepared for the catchments of South East Queensland. We would like to respectfully acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which this project takes place, and Elders both past and present. We also recognise those whose ongoing effort to protect and promote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures will leave a lasting legacy for future Elders and leaders. Table of Contents

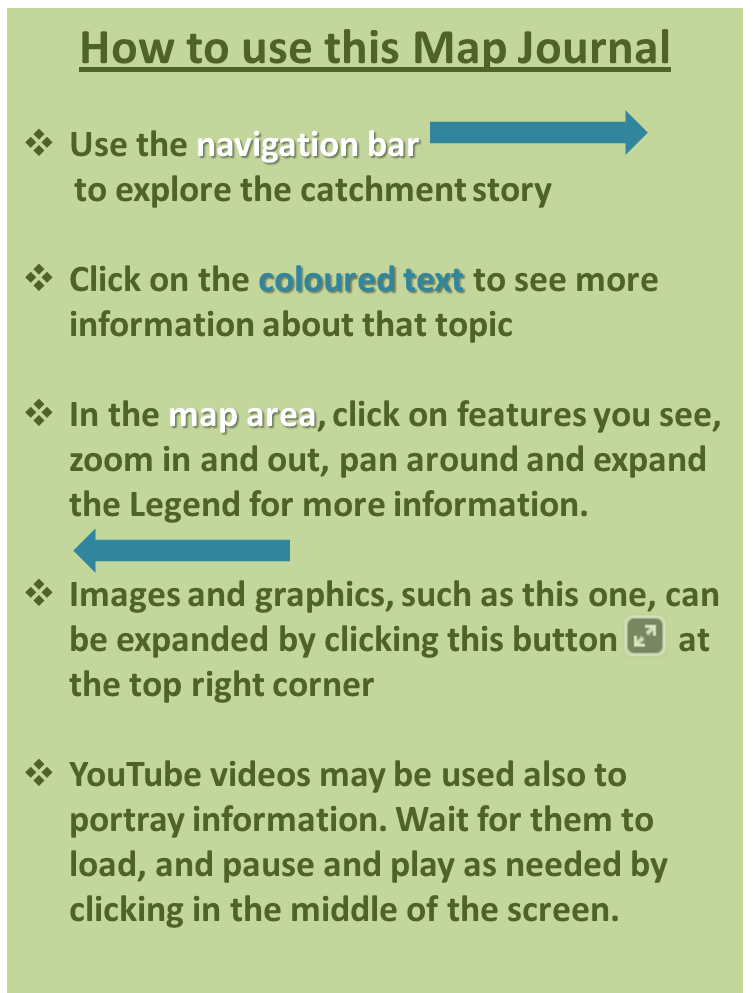

Understanding how water flows in the catchmentTo effectively manage a catchment it is important to have a collective understanding by all stakeholders of how the catchment works. This Map Journal gathers together information from expert input and data sources to provide that understanding. The information was gathered using the ‘walking the landscape’* process, where experts systematically worked through a catchment landscape in a facilitated workshop, to incorporate diverse knowledge on the landscape components and processes, both natural and human. It is focussed on water flows and the key factors that affect water movement. The Map Journal was prepared by the Queensland Wetlands Program in the Queensland Department of Environment and Science in collaboration with local partners. Main photo: Tree planting along upper Brisbane River, Photo by Seqwater *Walking the Landscape—A Whole-of-system Framework for Understanding and Mapping Environmental Processes and Values (Department of Environment and Heritage Protection 2012) - see links at the end of this map journal for further information. How to view this map journal

Please note that the use of the terms 'Catchment' and 'Basin' are sometimes used interchangeably. In this map journal the term 'Catchment' has been used. Map Journal for the Upper Brisbane catchment - water movementThis Map Journal describes the location, extent and values of the Upper Brisbane catchment. It demonstrates the key features which influence water flow, including geology, topography, rainfall and run-off, natural features and human modifications and land uses. Knowing how water moves in the landscape is fundamental to sustainably manage the catchment and the values it provides. Main photo: Emu creek and surrounding topography, Photo by Seqwater Upper Brisbane Catchment StoryThe Upper Brisbane catchment is located north west of Brisbane. The Upper Brisbane Catchment has an area of approximately 5,493 square kilometres (~40% of the Brisbane River catchment). (Click to play animation) This catchment is one of the northern catchments in South East Queensland, extending from the headwaters along the Great Dividing Range in the west, Brisbane and Jimna Ranges in the north and the D’Aguilar Range to the east. The Upper Brisbane River drains into Lake Wivenhoe. The Upper Brisbane River catchment is located to the west of the Stanley catchment which also flows into Lake Wivenhoe. Water from the lake then flows through the Mid-Brisbane River, where it is joined by Lockyer Creek and the Bremer River. The river then flows through the Lower Brisbane catchment before draining into Moreton Bay. The catchment includes a significant part of the Somerset Regional Council area, as well as including part of the Toowoomba Regional Council area and South Burnett Regional Council. Values of the catchmentThe Upper Brisbane River catchment contains many environmental, economic and social values and includes the townships of Esk, Toogoolawah, Harlin, Moore, Linville, Blackbutt, Benarkin, Yarraman, Cooyar and Crows Nest. There are also many areas for recreational activities such as camping, canoeing, fishing and bush walking. It is also of note that there has been significant clearing throughout the catchment for grazing and agriculture. Please note there is a drop down legend for most maps and it can be accessed by clicking on 'LEGEND' at the top right of the map. On this map you can use the drop down legend for the protected areas. Main image: Vegetation along Cressbrook Creek, Photo by Seqwater Values of the catchment - economicThe dominant industry in the area is grazing, with some intensive agriculture such as cropping, pastures and horticulture. Forestry is a significant industry with large areas of plantations (predominantly Hoop pine and some exotic pine) as well as managed native forests. There are also considerable areas of natural bushland in Protected Areas. These different land use types combine to make up the land use of the Upper Brisbane Catchment.*** Forestry in Perseverance catchment, Photo by by Toowoomba Regional Council Fodder harvesting, Cressbrook Creek floodplain, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Harvesting crop for silage, Pinelands, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Farming at Pinelands, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water *Please note the rural residential areas shown include rural residential as well as other residential area types. **Please note sand and hard rock extraction shown are within KRA (Key Resource Areas) only. KRAs are identified locations containing important extractive resources of state or regional significance worthy of protection for future use. Some KRAs include existing extractive operations (see link at end of map journal for more information). ***See links at end of this map journal for further details regarding land use classification. Main photo: Cattle grazing near Hays Landing Recreation Area, Lake Wivenhoe, Photo by Seqwater Values of the catchment - Wivenhoe DamWivenhoe Dam was completed in 1984 for the dual purposes of water supply for the region and for flood mitigation. Wivenhoe Dam is the principal water supply for the SEQ region. At full supply capacity, the dam holds approximately 1.2 million megalitres (ML), with a total storage capacity of approximately 3.1 million ML*. Wivenhoe Dam is a very popular recreation destination, with a wide variety of activities and facilities available. There are six main recreation areas: Cormorant Bay, Hamon Cove, Logan Inlet, O'Shea's Crossing, Spillway Lookout and Billies Bay/Hays Landing. *Sourced from Seqwater Main photo: Wivenhoe Dam wall, Photo by Seqwater Natural landscape features - geology and topographyGeology in the catchment is varied, with the majority of rock types in the catchment being hard rocks with limited groundwater recharge ability and high surface water run-off. There is minimal alluvium in the catchment relative to its size. There are some sedimentary rocks that have water infiltration which percolates into the watertable. The catchment contains some major fault lines from north-west to south-east where the Brisbane River runs. Main photo: Cat's claw creeper along Emu Creek, Photo by Seqwater Natural features - rainfallThe Upper Brisbane catchment receives moderate-low rainfall compared to the rest of the South East Queensland region and forms a major runoff area for Brisbane water supply into Lake Wivenhoe. The highest rainfall occurs along the ranges to the North East of the catchment and some areas to the South. The lowest falls are in the west of the catchment. Climate Data Online, Bureau of Meteorology Natural features - vegetationVegetation affects how water flows through the catchment, and this process is affected by land use and management practices. Eucalypt woodlands and open forests, and dry rainforests and scrubs are the main preclear vegetation communities of the catchment. Throughout the rest of the catchment there were patches of wet eucalypt open forests on ranges, as well as eucalypt open forests to woodlands on floodplains and eucalypt dry woodlands on inland depositional plains. These different vegetation types combine to make up the preclearing vegetation of the Upper Brisbane catchment. This vegetation slowed water, retaining it longer in the landscape and recharging groundwater aquifers, and reduced the erosion potential and the loss of soil from the catchment. Cressbrook catchment after 2019 bushfire, Photo by Toowoomba Regional Council Vegetation near Hay's Landing Recreation Area, Photo by Seqwater Yellow Box Grassy Woodland along drainage, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Cat's claw creeper along Brisbane River, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Main photo: Blue Gum Alluvial Plains, Yimbun, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water *Broad Vegetation Groups derived from Regional Ecosystems. Regional Ecosystems are vegetation communities in a bioregion that are consistently associated with a particular combination of geology, landform and soil. Modified features – vegetation and land useSome of the catchment was historically cleared (see below) for settlement and agriculture such as grazing, crops and forestry, with increasing rural residential and rural living development in recent years. Some areas of vegetation have regrown since initial clearing. These developments and activities change the shape of the landscape and can modify water flow patterns. Explore the Swipe Map using either of the options below.*

*Depending on your internet browser, you may experience issues. Please note this application takes time to load. Agriculture alongside Brisbane River near Cooeeimbardi (2018), Photo by Seqwater Agriculture alongside Brisbane River near Cooeeimbardi (2020), Photo by Seqwater *Please note the residential areas shown include rural residential as well as other residential area types. Main photo: Cooeeimbardi Creek South Branch, Photo by Seqwater Modified features - channels and infrastructureThough limited in comparison to many catchments in South East Queensland, the development of buildings and infrastructure such as roads, railways and creek crossings creates impermeable surfaces and barriers that redirect water through single points or culverts, leading to channelling of water. This increases the rate of flow and the potential for erosion. Modifications to channels such as straightening and diversions, can also increase flow rates. Modified features - dams and weirsDams and weirs can also modify the natural water flow patterns, by holding water and controlling the timing and quantity of releases. Large water storages, such as Lake Cressbrook, Lake Perseverance, Lake Wivenhoe, as well as small farm dams and weirs all modify water flow by holding water into a confined area. Cressbrook and Perseverance Dams comprise a major water supply for Toowoomba. There is interdivisional water transfer between the two of them. See Toowoomba Regional Council diagrams below. Water from all the major creeks within the catchment flow toward Wivenhoe Dam. Water from Somerset Dam is released into Wivenhoe Dam, which in turn supplements the natural flow of the Brisbane River. The Tarong Power Stations have access to water from Boondooma Dam and Lake Wivenhoe. The Stations draw 68% of their supply from Boondooma Dam and 32% from Lake Wivenhoe (as at 1 October 2019)*. SEQ Water Grid diagram shows Tarong Water Station's linkage with Wivenhoe Dam - provided by Seqwater (link available at the end of the catchment story). Increased erosion from historic clearing, fragmented riparian vegetation, inappropriate development and land management, and weed invasion in the catchment can drive poor water quality in the reservoir, particularly during flow events, and contributes to algal blooms which can create a treatment challenge. Diagrams/images above provided by Toowoomba Regional Council. *Source: Stanwell - 1 Oct 2019 Water qualityWater quality is influenced by run-off and point source inputs such as sewage treatment plants, septic tank seepage and stormwater discharge. Sewage treatment plants (STPs) for the region include Toogoolawah STP, Esk STP and Blackbutt STP. From 2016 to 2019, the Upper Brisbane catchment has received a Environmental Condition Grade of D in the annual Report Card. However while this represents an average across the sites tested, waterway condition across the whole catchment varies significantly with some reaches in good condition to others which are degraded and in poor condition.* *Healthy Land and Water Upper Brisbane Catchment Report Card (for current report see links at end of map journal). Excerpt from Healthy Land and Water report card (colours closer to green on the spectrum indicated a better score - see links at end of map journal for more information). Water flowWater flows across the landscape into streams and eventually into the Brisbane River. (click to see animation) Water may seep into, or infiltrate, the ground where it supports a variety of terrestrial and groundwater dependent ecosystems, can be used for other purposes (e.g. water supply), or, in the case of relatively steep slopes (e.g. upper catchment), may increase run-off potentially leading to flooding in areas where the floodplain has restricted channels and gullies. To effectively manage this catchment, it is important to understand how water moves within the catchment, and how the catchment’s natural and modified features affect water movement. The sub-catchmentsA catchment is an area with a natural boundary (for example ridges, hills or mountains) where all surface water drains to a common channel to form rivers or creeks. Larger catchments are made up of smaller areas, sometimes called sub-catchments. The Upper Brisbane catchment consists of large and small sub-catchments. The catchment can be divided into 12 smaller sub-catchments – Upper Brisbane River (headwaters), Monsildale Creek, Cooyar Creek, Emu Creek, Maronghi Creek, Upper Perseverance Creek, Upper Cressbrook Creek, Lower Cressbrook Creek, Western Wivenhoe, Middle Reaches of Upper Brisbane River (in Moore), Wivenhoe catchment and the Eastern Wivenhoe Catchment. The characteristics of each sub-catchment are different, and therefore water will flow differently in each one. Upper Brisbane River (headwaters)The Upper Brisbane (headwaters) sub-catchment includes the Brisbane River headwaters and Avoca Creek. It receives good rainfall in the upper, north east of the catchment, and due to the lack of porosity of the metamorphic geologies, it does not have very good groundwater recharge potential. This means the steep slopes, combined with good rainfall, may result in fast creek flows. The geology in the upper catchment runs in vertical bands west to east including Esk Formation, Neara Volcanics, Marumba Beds and Kimbala Granodiorite. Although there is a lower annual rainfall in the mid to lower areas of the sub-catchment, the higher rainfall and lack of porosity in the upper sub-catchment, means the mid and lower sub-catchment is still impacted by flash flooding in intense rainfall events. The mid Upper Brisbane sub-catchment is also steep to undulating. The Brisbane River in lower parts of this sub-catchment is characterised by a series of terraces and benches present (quaternary alluvium) which do not erode easily. However, the area does contain less fertile and more erodible soil types on the hills and slopes. Land use includes significant areas of State Forest and Hoop pine plantations at the top of the catchment with small areas of dryland and irrigated pasture, agriculture and plantations on narrow alluvial flats. However, due to a lack of water availability the majority of the sub-catchment is used for grazing. There is relatively intact riparian vegetation throughout with some increasing cat's claw creeper present. There are many creek crossings (bed controls) in the upper sub-catchment. There are more than 45 low river crossings in the Brisbane River headwaters, as well as some on Avoca Creek, that act as mini weirs in low flow but generally, water flows over them in high rainfall events. From top of Western Branch, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Brisbane River, Mt Stanley, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Brisbane River, crossing on Western Branch, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Brisbane River, crossing on Western Branch, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Brisbane River, Western Branch, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Brisbane River, Western Branch, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Brisbane River, Eastern Branch, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Monsildale CreekThe Monsildale Creek sub-catchment includes Monsildale, Middle and Marumbah Creeks. It has good rainfall in the upper sub-catchment area. Good rainfall combined with metamorphic, sandstone geologies and steep to undulating slopes result in fast flow creeks and a low recharge potential. The geology runs in vertical bands west to east including Esk Formation, Neara Volcanics, Marumba Beds and Kimbala Granodiorite. In the lower western branch of the sub-catchment there is Esk Formation with more erodible, less fertile soil types. The remainder of the sub-catchment receives lower rainfall and varies between rocky areas and sandy creek beds. Some channels in the upper and mid areas are incised and gorge-like (confined). While in the lower section the sandy channel is wider, has some benches, bars and poor bank stability, but greater recharge potential. There is some irrigation for pasture however the water supply in this area is not enough to support farming industries, so much of the sub-catchment has been cleared and used for forestry and grazing. The catchment still contains some native riparian vegetation however it is fragmented and in thin strips. Similarly to the Upper Brisbane sub-catchment, there are many creek crossings (bed controls) in the upper region of this sub-catchment. There are many low river crossings that act as mini weirs in low flow but the water generally flows over them in high rainfall events. Vegetation coverage is good. There is some erosion related to steepness.* *Source: Watkinson, A., Bartkow, M., Raiber, M., Cox, M., Hawke, A. and James, A. (2013). Of droughts and flooding rains: impacts of extremes on groundwater-surface water connectivity. Water. (40: 2-7). (link at the end of the catchment story) Lower Monsildale Creek, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Monsildale Creek, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Middle Creek, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Cooyar CreekThe Cooyar creek catchment includes Oaky, Logyard, Krugers Gully, Sandy, Yarraman, Rocky and Taromeo Creeks. The headwaters start on the Great Diving Range and includes a plateau as well as steep to undulating hills and creek flats. This sub-catchment has a highly variable geology, compared to other sub-catchments in the region, and includes Main Range Volcanics, Esk Formation, Maronghi Creek Beds and Tarong Beds. There are good infiltration rates and groundwater recharge potential in the upper catchment. With low rainfall, the upper catchment has ephemeral creeks that run slowly and gently unless in times of high flow. The lower down the catchment, the lower the porosity and the more permanent the water flow and waterholes. In the mid catchment, above the Pukallus and McCauley Weirs, flows are near permanent and the creek has incised into the landscape. The land use in the catchment is mainly forestry, cattle grazing on native vegetation with some limited irrigated cropping on the flats and dryland cropping on fertile basalt upland soils. In the lower catchment, around Blackbutt, there is an historic quarry, dryland farming and irrigated perennial tree crops as well as significant peri-urban areas. Around Spring Creek there is an area of Palm Rainforest that is spring fed. Although some natural saline seepage may have impacted the vegetation in Logyard Creek, the riparian vegetation throughout the rest of the sub-catchment is relatively good, with the exception of the lower sub-catchment area which has less riparian vegetation. Note that cat's claw creeper and broad-leaf privet are present along the riparian corridor throughout the sub-catchment. There are a number of water storage areas including a private weirs in Oaky and Cooyar (below Cooyar-Kooralgin Road) creeks, Pukallus Weir (near D’Aguilar Hwy), McCauley Weir (former Nanango water supply, no longer used) and an old weir at Yarraman. Some water supply for Yarraman is drawn from the Pukallus weir, while the majority of it is provided by Boondooma/Nukku (Boondooma to Blackbutt) pipeline (not Wivenhoe to Tarong). Irrigation is mainly concentrated along Cooyar Creek alluvium in Kooralgin. Water quality concerns in the area include salinity, turbidity and pathogens. Cooyar Creek and Logyard Creek can be saline (around Marburg geology) however, at the confluence with Brisbane River, salinity levels drop due to dilution. There is some salt seepage out of Oaky Creek and some water quality issues after high flows through weir. Properties are on septic systems and the Blackbutt Sewage Treatment Plant discharges to Taromeo Creek. Cooyar Creek (2004), Photo by Water Planning Ecology, Department of Environment and Science Upper Cooyar Creek at Rangemore, Photo by Bruce Lord, Health Land and Water Cooyar Creek, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Cooyar Creek, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Yarraman Creek, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Yarraman Creek Weir, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Pukallus Weir Cooyar Creek, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Upper Yarraman farming and forestry, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Emu CreekThe Emu Creek sub-catchment includes Emu, Gowrie, Mitchell, Bum Bum, Pierce, Salty Waterhole and Nukinenda Creeks. The headwaters of Emu Creek start in the Great Diving Range and are fairly steep in the upper and mid sub-catchment before flattening out in the lower catchment. The upper catchment geology means it is partially confined and has incised bank erosion (highly weathered basalt), the mid sub-catchment has waterholes and boulder bed streams leading to the finer gravels and sands semi-confined areas before spreading out into wider areas on the flood plain. There is erosion in the lower catchment, which is prevented in areas by vegetation such as bottle brush. The recharge capability of the catchment varies from the top to the bottom of the catchment from good porosity basalt to low porosity sandstone. So although the catchment has relatively low average annual rainfall, intense rainfall events can result in high flows, with water moving quickly down the streams, particularly through gorge sections where there is significant fall in elevation. The gorge vegetation, in the middle of the sub-catchment, is still in good condition however, much of the catchment has been cleared and there are major cat's claw creeper infestations along the creek. There are contiguous strips of riparian vegetation which differs in width due to land use. Emu Creek differs from many other catchments as there is alluvium at the top of the catchment before entering the gorge area. There are some isolated areas of salinity in the Rocky Gorge Creek and Salty Waterhole Creek which dilutes when it comes in contact with the water from Emu Creek. Land use includes grazing on native vegetation, State Forest on Blackbutt Range, forestry (Benarkin State Forest), conservation, cropping, animal husbandry, rural residential (e.g. Glenhowden) and peri-urban areas. Irrigation does occur from creek spear wells or small impoundments. Gowrie Creek at Djuan, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Emu Creek at Djuan, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Cat's claw creeper along Emu Creek, Photo by Seqwater Emu Creek, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Pierces Creek, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Emu Creek waterhole at Glenhowden, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Main photo: Emu creek, Photo by © Queensland Museum, Bruce Cowell Maronghi and Ivory CreeksThe Maronghi Creek sub-catchment includes Maronghi, Middle, Maria and Ivory Creeks. Maronghi and Ivory Creeks headwaters drain east off the basalt of Anduramba Range at The Bluff. There are also gorges just before Maria and Maronghi Creeks join. Maria, Ivory and Maronghi Creeks have waterholes as well as incised channels and erosion in the gullies in the mid sub-catchment. In the lower sub-catchment there is some braiding of the sandy channel with sand bars. The reach behind the town of Harlin has some significant erosion (bank scour). The sub-catchment contains predominantly hard geologies (granites and metamorphics) so recharge capability is typically low. The catchment has relatively low rainfall and there are a number of dams and bores in alluvium being used in the area. Confluence of Brisbane River and Maronghi Creek, near Harlin, Photo by DNRME The main land uses include grazing of native vegetation with limited areas of cropping on narrow alluvial flats. Vegetation in the catchment has predominantly been cleared, with only some strips remaining on hills and elevated areas. Ivory Creek, Eskdale, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Ivory Creek, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Maronghi Creek, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Lower Maronghi Creek, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Upper Perseverance CreekThe Upper Perseverance Creek sub-catchment includes Perseverance, Ballard, Pipe Clay and Buckamara Creeks. Upper Perseverance Creek has good rainfall (>1000 mm/yr) throughout the majority of the catchment. Some creeks in the region are semi-permanent and farm dams do dry out during periods of low rainfall. The west portion of the sub-catchment receives slightly lower rainfall than the east. The headwaters of the creek are steep. The geology is Tertiary Main Range Volcanics with Main Range Volcanics, Woogaroo sub group and Crows Nest Granite. The basalt has good recharge and release potential, as opposed to the granite areas which do not. This means that the creeks are narrow and incised in parts. They tend to have a rocky base and some slips and seepage occurs in low flows. Land use includes grazing on native vegetation, State Forest at the rim of the catchment, forestry around the lake and tree crops at Hampton, conservation and rural residential development, perennial horticulture and intensive animal husbandry. Water extraction has increased with more intensive horticultural development in this sub-catchment since the 1980’s and 1990’s. Perseverance Dam (approx. 30,000 ML*) has inter-basin transfer via a pump to Pechey Reservoir (high point) which can gravity feed, via pipe, to the Toowoomba Regional Council Water Treatment Plant. There is limited recreation on Perseverance Dam. Water quality is good, although reports of blue green algae/cyano bacteria outbreaks in the Dam do occur. Riparian vegetation is good with wide strips that become fragmented near main roads. There are pockets of rainforest (related to basalt seeps) in higher reaches of the sub-catchment and protected areas within Ravensbourne National Park. There are some areas of privet and lantana infestations to the east of the sub-catchment and along Perseverance Creek. Upper Perseverance catchment, Photo by Toowoomba Regional Council Perseverance Creek, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Perseverance Dam, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Palm forest, Palmtree, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water *Sourced from the Toowoomba Regional Council website Upper Cressbrook CreekThe Upper Cressbrook Creek includes Crows Nest, Old Woman’s Hut, Bald Hills and Rocky Creeks. The sub-catchment is steep with low rainfall. The creek flow can be fast in times of high flow and travels through gorges (e.g. Cressbrook Gorge) and boulder beds. It can be incised and confined and has some erosion*. The geology is varied and includes a basalt cap along the range, Cooby Trachyte Member, Marburg Subgroup, Crows Nest Granite, Woogaroo strip, Sugarloaf Metamorphics, and on the very southern section Crows Nest Granite, Hampton Road Rhyolite and Pinecliffe Formation. The Cressbrook Creek Dam (at end of sub catchment) has a pump that pumps water to Jockey reservoir, then to Pechey. There are also releases related to water levels in lower Cressbrook weirs and an annual allocation to pump from Wivenhoe to flush out pipes. The Cressbrook Creek Dam is part of the Wivenhoe pipeline network see “Modified features – dams and weirs” section earlier in the catchment story for more information. Good groundwater quality although there is historic sediment loss, deposition in streams and salt scalds and seeps in upper catchment. Crows Nest Common Effluent Drainage (CED) scheme is used to irrigate pastures. Land use includes grazing on native vegetation, Crows Nest National Park area, animal husbandry, irrigated perennial horticulture, some ex grazing and vegetation around dam. Riparian vegetation similar to Upper Perseverance Creek but with lengths of clearing on hills. Includes good contiguous, wider vegetated strip below Crows Nest and Old Woman's Hut Creeks. Bald Hills Creek, Crows Nest, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Junction Crows Nest and Bald Hills Creeks, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Main photo: Cressbrook dam, Photo by Seqwater *Source: King, A. C., Raiber, M., Cox, M. E. (2014). Multivariate statistical analysis of hydrochemical data to assess alluvial aquifer–stream connectivity during drought and flood: Cressbrook Creek, southeast Queensland, Australia. Hydrogeology Journal (22: 481-500). (link at the end of the catchment story) Lower Cressbrook CreekThe Lower Cressbrook sub-catchment includes Cressbrook Creek and main tributaries Kipper and Oaky Creeks. The sub-catchment has good rainfall in the upper sub-catchment and lower rainfall in the mid (above weir and Kipper Creek) to lower catchment (below weir). In the upper sub-catchment it is steep and gorge-like. Incised and confined channels with isolated erosion and gravel and rocky boulders. In the mid sub-catchment the channels are deep with large bends and gorge country before flattening where the water spreads out and slows down resulting in minimal erosion. This sub-catchment has paleo channels, large bends and is influenced by the dam (e.g. used to be waterholes)*. The geology includes Sugarloaf Metamorphics, Pinecliffe Formation, Woogaroo, Hampton Road Rhyolite and Esk Formation (groundwater extraction). The impact of the upstream Dams and lower Cressbrook weirs have significantly modified flows and reduced the number of waterholes. The weirs are fish barriers (fish passage every 1 in 10 years). Land use includes grazing on native vegetation, forestry, irrigated perennial horticulture, animal husbandry, gravel extraction, rural residential areas and Toogoolawah Sewage Treatment Plant. Cressbrook Creek and Lower Cressbrook Creek Weirs are both recharge weirs. Lower Cressbrook Weir (at end of sub catchment) is in a declared groundwater area under Moreton Resource Operations Plan (ROP). There have been large changes to the creek with sand slugs, reduced flow, and flushing. Due to the geology and modified water flows (reduced flushing), there are isolated saline areas, usually at the edge of the alluvium, when the aquifer is drawn down. The water quality is also impacted by some erosion, small scalds and saline seeps. In flood events - turbidity, nutrients and pathogens affect water quality before the water enters Boundary Creek. There is good vegetation coverage from historical production forestry and native bushland on ranges and hills. In the mid sub-catchment (above the weir) the vegetation is patchy and much of the riparian zone in this area and the lower Cressbrook catchment contains significant weed infestations with cat's claw creeper and Chinese elm dominating. Cressbrook Creek, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Cressbrook Creek, Esk Crows Nest Rd, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Cressbrook Creek, cats claw creeper, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Cressbrook Creek, cats claw creeper, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water *Source: King, A. C., Raiber, M., Cox, M. E. (2014). Multivariate statistical analysis of hydrochemical data to assess alluvial aquifer–stream connectivity during drought and flood: Cressbrook Creek, southeast Queensland, Australia. Hydrogeology Journal (22: 481-500). (link at the end of the catchment story) Western WivenhoeWestern Wivenhoe sub-catchment also includes Sandy, Redbank, Gallanani, Esk and Coal creeks. The geology is steep to undulating on Woogaroo Subgroup and Esk Formation (Gallanani Creek and lower catchment below Esk). There is a gorge that has hard geology and the creeks are ephemeral with water holes, sand, sandstone and boulder beds. Redbank Creek has a gravel bed with a sand section. It rarely flows, but when it does, it tends to be a fast flow due to rapid changes in elevation off the Deongwar Range. Landslips and channel erosion occur, particularly in the lower parts of the sub-catchment. There is a natural flood constriction at Esk and a main road constriction in the upper catchment (floods over road). There is good rainfall in the upper sub-catchment with lower rainfall in the lower sub-catchment. Water quality is very good, but can be sandy when eroded. Gallinani Creek has alluvium, sodic soils and salinity outbreaks (locally). Land use includes grazing, forestry, managed resource production, farming on valley floors and lower slopes (alluvium), irrigated seasonal horticulture, peri-urban above Esk and Esk Sewage Treatment Plant (providing irrigation via off-stream dams). There are also a number of bores and soaks. Redbank Creek farming, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Redbank Creek, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Coal Creek riparian corridor, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Middle Reaches of the Upper Brisbane River (in Moore)The Middle Reaches of Upper Brisbane River (in Moore) sub-catchment includes the main channel as well as Wallaby (upper west side of river), Kangaroo, Spring, Neara, Gregors (upper east side of river), and Lagoon Creeks (North of Esk). Incised channels, some steep banks and erosion in Wallaby Creek. There is also erosion north of Linville and south of each of the confluences. On the east side, Spring and Neara creeks have chains of ponds and may be spring fed. The lower main macro-channel is confined between hard rock geologies and includes Neara Volcanics and Esk Formation. There is some deposition of sediments in bars. Lagoon Creek has a chain of ponds on a broad modified floodplain. Land use is predominantly irrigated and dryland cropping (alluvium), but also includes grazing on native vegetation, forestry, animal husbandry, irrigated perennial horticulture, mining (extraction in-stream and within macro-channel). Extraction site near Gregor's Creek Bridge, Photo by Seqwater Private river crossing to extraction plant, Photo by Seqwater There is some influence from Wivenhoe Dam within the lower end of this sub-catchment. In high flow events water will back up. There is significant erosion in this sub-catchment due to its position in the landscape, the confluence of a number of large tributaries, erodible alluvial soils and impacts from significant sand and gravel extraction at a number of sites along the Brisbane River. SEQ Catchments coordinated a restoration project involving the establishment of a series of pile fields to address severe erosion along Harlin reach, following major floods in 2011 and 2013. The sub-catchment riparian vegetation is fragmented and very limited in places. Kangaroo and Spring creeks have patchy/fragmented riparian vegetation with limited erosion. Neara Creek also has limited and fragmented riparian vegetation but more erosion occurs. Brisbane River near Linville, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Severe Bank Erosion 2011 Harlin, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Severe Bank Erosion 2011 Harlin, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Harlin restoration site 3 March 2017, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Harlin restoration site 3 March 2017, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Spring Creek, Harlin, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Gregor's Creek at Brisbane River, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Brisbane River at Cressbrook, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Wivenhoe CatchmentThe Wivenhoe Catchment includes Paddy's Gully and Logan Creek. The sub-catchment has low rainfall with ephemeral creeks. The undulating to flat landscape geology is mainly the Woogaroo Subgroup with some Esk Formation and Neara Volcanics. There is some channel erosion in Paddy's Gully which is incised and deeply erodes at the lower end. Paddy's Gully is the biggest creek in the sub-catchment and has spring flow. Land use includes forestry at top end of lake, grazing on native vegetation, turf and rural residential. The riparian vegetation is sparse and has been cleared for Wivenhoe Dam. Historically the sub-catchment was eucalyptus woodland. The existing woodland has thickened significantly since the dam was completed. Lake Wivenhoe up old river channel, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Turbid inflow to Wivenhoe Dam, Photo by Seqwater Water offtake towers, near Esk, Photo by Seqwater Main photo: Wivenhoe Dam wall, Photo by Seqwater Eastern Wivenhoe CatchmentThe Eastern Wivenhoe sub-catchment includes Sandy, Middle, Northbrook and Kipper creeks which join in the lower catchment. The geology starts in the steep slopes of the Neranleigh Fernvale Beds with a narrow strip of Northbrook Volcanics. Further down the sub-catchment there are Northbrook Beds, Bryden Formation and Neara Volcanics. Northbrook has high rainfall throughout most of the year in comparison to the low rainfall experienced throughout the rest of the sub-catchment. The upper sub-catchment creeks have gorges, boulders, cobbles, and waterholes in the shallow v-shaped channels. As the creek moves into the lower catchment the channels are still narrow but become deep and stable. Land use includes grazing on native vegetation, National Park, conservation, state lands, forestry and rural residential areas. Wivenhoe Dam may have an influence on water quality in the lower regions of the creeks, but in general, the water quality is good. The sub-catchment is well vegetated in the hills and gorge areas have pockets of rainforest. Lower in the catchment the vegetation becomes fragmented and contains cat's claw creeper. Although there is less vegetation in the lower sub-catchment there are timbered outcrops. Kipper Creek, Photo by Bruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water SummaryThis catchment shows how natural and modified features within the landscape impact on how water flows. Some areas within the Upper Brisbane catchment are in relatively good condition, particularly in some headwaters, while other parts aren’t as healthy (degraded/poorer condition) due to historic clearing, channel and flow modification, and weed invasion. Water quality issues need to be managed to ensure that the residents of South East Queensland receive a safe and secure drinking water supply. This will also assist in minimising the impacts on values (e.g. agricultural, landscape, waterway, biodiversity) within the catchment and downstream in the Brisbane River and Moreton Bay. Knowing how the catchment functions is important for future planning, including climate resilience. With this knowledge, we can make better decisions about how we manage this vital area. Main photo: Agriculture alongside Emu Creek (top left); Grass tree, near Hays Landing Recreation Area (top right); Agriculture alongside lower Cressbrook Creek (bottom left); Upper Brisbane River, Cressbrook (bottom right), Photos by Seqwater AcknowledgementsDeveloped by the Queensland Wetlands Program in the Department of Environment and Science in partnership with: Council of Mayors South East Queensland Healthy Waterways (Healthy Waterways and Catchments) South Burnett Regional Council This resource should be cited as: Walking the Landscape – Upper Brisbane Map Journal v1.0 (2020), presentation, Department of Environment and Science, Queensland. Photos provided byBruce Lord, Healthy Land and Water Bruce Cowell (Queensland Museum) Water Planning Ecology, Department of Environment and Science Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy The Queensland Wetlands Program supports projects and activities that result in long-term benefits to the sustainable management, wise use and protection of wetlands in Queensland. The tools developed by the Program help wetlands landholders, managers and decision makers in government and industry. Contact wetlands♲des.qld.gov.au or visit wetlandinfo.des.qld.gov.au This Map Journal has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this Map Journal are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this Map Journal is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. This resource should be cited as: Walking the Landscape – Upper Brisbane Journal v1.0 (2020), presentation, Department of Environment and Science, Queensland. Data sources, links and informationSoftware UsedArcGIS for Desktop | ArcGIS Online | Story map journal Some of the information used to put together this map journal can be viewed on the QLD Globe. The Queensland Globe is an interactive online tool that can be opened inside the Google Earth™ application. Queensland Globe allows you to view and explore Queensland spatial data and imagery. You can also download a cadastral Smartmap or purchase and download a current titles search. More information about the layers used can be found here:Flooding Information:South Burnett Regional Council Additional sourcesLinks:Upper Brisbane Healthy Land and Water Report Card Main photo: Farmland in the Perseverance catchment, Photo by Toowoomba Regional Council Last updated: 23 July 2020 This page should be cited as: Department of Environment, Science and Innovation, Queensland (2020) Upper Brisbane Catchment Story, WetlandInfo website, accessed 8 May 2025. Available at: https://wetlandinfo.des.qld.gov.au/wetlands/ecology/processes-systems/water/catchment-stories/transcript-upper-brisbane.html |

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation