|

|

Redlands Catchment StoryThe catchment stories use real maps that can be interrogated, zoomed in and moved to explore the area in more detail. They take users through multiple maps, images and videos to provide engaging, in-depth information. Quick facts

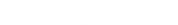

Quick linksTranscriptUnderstanding how water flows in the catchmentTo effectively manage a catchment it is important to have a collective understanding of how the catchment works. This map journal gathers information from experts and other data sources to provide that understanding. The information was gathered using the ‘walking the landscape’ process, where experts systematically worked through a catchment in a facilitated workshop, to incorporate diverse knowledge on the landscape features and processes, both natural and human. It focussed on water flow and the key factors that affect water movement. The map journal was prepared by the Queensland Wetlands Program in the Queensland Department of Environment and Science in collaboration with local partners. How to view this map journalThis map journal is best viewed in Chrome or Firefox, not Explorer.

Please note that the use of the terms 'Catchment' and 'Basin' are sometimes used interchangeably. In this map journal the term 'Catchments' has been used. Furthermore, the Redland Catchments are typically portrayed as a Catchment but made up of approximately ten smaller catchments. Map journal for the Redlands Catchment—water movementThis map journal describes the location, extent and values of the mainland Redlands Catchment. It demonstrates the key features which influence water flow, including geology, topography, rainfall and run-off, natural features, human modifications and land uses. Knowing how water moves in the landscape is fundamental to sustainably managing the catchment and the services it provides. Redlands Catchments storyThe Redlands Catchment is located to the south-east of Brisbane with their headwaters in Mount Cotton and Mount Petrie. They fall mostly within the Redland City Council boundary, but also includes parts of the Brisbane City and Logan City council areas. The catchments approximately 281 km2 with approximately 525 km of stream network (click for animation). The Redlands Catchment includes Tingalpa, Hilliards, Eprapah and Moogurrapum creeks, together with numerous smaller waterways and drainage lines. All waterways flow to southern Moreton Bay. The broader Brisbane catchments are located to the north-west, and the Bremer, Logan, Albert and Gold Coast catchments are located to the west and south. Values of the catchmentThe Redlands Catchments contain many environmental, economic and social values. The catchment includes the heavily developed areas of Wynnum, Manly, Birkdale, Capalaba, Cleveland, Thornlands, Victoria Point, Redland Bay and Rochedale. There has been substantial development over time, particularly across coastal areas (click to see interactive swipe map showing changes in development over time - zoom to an area of interest).* The catchment is mostly residential, typically with rural residential** in the upper parts and urban residential further downstream. It offers a relaxed bayside lifestyle with ready access to both the city and southern Moreton Bay, together with great coastal views. The catchment supports a range of different farming activities. Historically, the productive red soil on the lower-lying parts was used for grazing, horticulture and cropping, however these areas are now heavily modified by urban development. There are protected areas and public nature refuges*** (both managed by state government) across the catchment, including large areas of mangrove and saltmarsh. There is also reserve land that is in public ownership (managed by local government). Please note there is a drop-down legend for most maps and it can be accessed by clicking on 'LEGEND' at the top right of the map. On this map you can use the drop down legend for the residential, farming and protected areas. *This application may take time to load. **Please note the residential areas shown include rural residential as well as other residential area types. ***Protected areas of Queensland represent those areas protected for the conservation of natural and cultural values and those areas managed for production of forest resources, including timber and quarry material. The mapped nature refuges are part/s or whole of Lot/s on plan and are gazetted through a voluntary conservation agreement between the state government and private land owner/s. Main photos. Capalaba centre (top left), farming in the upper Eprapah Creek sub-catchment (top right), Lighthouse Hotel with mangroves and rocky foreshore, Cleveland Point (bottom left), Venman Bushland National park (bottom right) - all provided by Department of Environment and Science. Values of the catchment—economicUrban development and residential living are strong drivers of the local economy. Tourism is also a major industry. Destination parks such as Wellington and Cleveland points offer recreation opportunities with bay views, and access to launching sites for boats and paddle crafts. Fertile soils support grazing on native pastures and horticulture (including grapes, flowers and bulbs, fruit trees, vegetables and herbs, and turf), together with horse studs and irrigated cropping. There are also poultry farms in the southern catchments. There is mining and quarrying in the headwaters of Tingalpa, Wallaby, Hilliards and Moogurrapum creeks, including a hard rock Key Resource Area.* These different land use types combine to make up the land use of the Redlands Catchment. Main photo. Cleveland Point park - provided by Department of Environment and Science. *Please note hard rock extraction shown are within KRA (Key Resource Areas) only. KRAs are identified locations containing important extractive resources of state or regional significance worthy of protection for future use. Some KRAs include existing extractive operations (see link at end of map journal for more information). Values of the catchment—environmentalThe catchments contain a number of protected areas, including Venman Bushland National Park and Daisy Hill Regional Park (Priestdale Park). The catchments also include public nature refuges, conservation and natural areas, and parts of the Moreton Bay Ramsar site. The wetlands and creeks of the catchment provide habitat for many important species, including wader birds, several frogs, the lesser swamp orchid and native jute. One of the key natural features of the catchments is the diversity of ornate rainbowfish, where different colour morphs exist in different systems such as Buhot and Coolnwynpin creeks. The diversity is maintained by the lack of connection between the small waterways. Estuarine areas support important mangrove, saltmarsh and seagrass. There are large areas of mangrove and saltmarsh associated with Lota, Tingalpa, Hilliards and Eprapah creeks. Information about the different types of wetlands shown in this mapping is provided here. Main photo. Mangroves along the Cleveland Point foreshore - provided by Department of Environment and Science. Values of the catchment—socialProtected areas provide recreational activities, such as bush walking, trail bike riding, bird watching and kayaking, and also substantial social and health benefits. Large areas of the catchment, often along waterways, are used for recreation (e.g. parks, sporting fields and golf courses). The waterways are extensively used for boating and fishing. Many of the riparian areas and reserves also contain sites of aboriginal cultural heritage significance including bora rings, scar trees and shell middens. Historically, Moreton Bay and major waterways such as Tingalpa Creek would have provided indigenous people with a rich food source. Europeans settled the area in 1824. Early land uses including cattle grazing, timber and cropping. Main photo. Kayaks on the southern bay - provided by Redland City Council. Natural features—geology and topographyThe headwaters are underlain by mostly impervious or low permeability fractured metamorphic rock. These areas have fast surface water run-off, especially the steep landforms of upper Priest Gully (Mount Petrie) and Tingalpa and Eprapah creeks (Mount Cotton). There are large areas of sedimentary rock in undulating land forms across the lower-lying areas. run-off from these lower porosity rock areas flows into alluvium and is underlain by impervious rocks. These areas support wetlands and stream flow. There are also several perched wetlands across the catchments. There are large areas of alluvium along channels across the catchments, together with low-lying coastal swamps and Petrie Formation (basalt) lining most of the shore. These basalts enable high amounts of water infiltration and groundwater recharge, which provides an important contribution to springs, creeks, wetlands and terrestrial vegetation year round. These different rock types combine to make up the geology of the Redlands Catchment. Natural features—rainfallAll of the catchments experience high average rainfall (1,001-1,500mm/year). Natural features—vegetationVegetation affects how water flows through the catchment, and this process is affected by land use and management practices. Native vegetation slows water, retaining it longer in the landscape and recharging groundwater aquifers, and reducing the erosion potential and the loss of soil from the catchments. Historically, most of the catchments contained eucalypt forests. There were areas of melaleuca forests across the catchments, together with wet eucalypt forest and rainforests and scrubs in the southern headwaters. In the lower-lying areas there were mangrove forests, together with other coastal communities including heath. These different vegetation types combine to make up the preclearing vegetation of the Redlands Catchment**. Main photo. Spoonbill foraging in heavily vegetated wetland - provided by Redland City Council. *Broad Vegetation Groups derived from Regional Ecosystems. Regional Ecosystems are vegetation communities in a bioregion that are consistently associated with a particular combination of geology, landform and soil. **Pre-clearing vegetation was determined from remnant vegetation, aerial photographs, and ecological and in some instances historical knowledge (see links at end of this map journal for more information about the mapping of regional ecosystems). Modified features—vegetation clearingThere are large areas of remnant vegetation across most of the upper parts of the catchments. There is little to no remnant vegetation in the lower parts of the catchment. Mangroves line some waterways and parts of the shoreline. In the upper parts, large areas of vegetation have regrown since initial clearing, however there has been little to no regrowth across the lower-lying areas. Explore the Swipe Map using either of the options below.*

These developments and activities change the shape of the landscape and can modify water flow patterns. *Depending on your internet browser, you may experience issues with one or the other. Please note this application takes time to load. Modified features—channels and infrastructureBuildings and important infrastructure such as railways, roads and creek crossings create impermeable surfaces and barriers that redirect water through single points or culverts, leading to channelling of water. This increases the rate of flow and the potential for erosion. Modifications to channels, such as straightening and diversions, can also increase flow rates. Several canal, lake and marina developments also modify flow, including Raby Bay on lower Ross Creek, and Aquatic Paradise and Sovereign Waters on lower Tarradarrapin Creek. Infilling of wetlands (billabongs) has also substantially modified flow (and reduced habitat), particularly across lower Tingalpa, Coolnwynpin and Eprapah creeks. Many of the catchments contain areas that have been heavily developed and there are many impermeable surfaces. Main photos. Road and walkway crossings at Fellmonger Park, Ormistion (top left), Raby Bay Marina (top right), Aquatic Paradise canals (bottom left), Sovereign Waters foot bridge (bottom right) - all provided by Department of Environment and Science. Modified features—dams and weirsDams and weirs also modify the natural water flow patterns, by holding water. This affects how much water flows through the system. The catchment has several large dams and weirs. The Tingalpa Reservoir (Leslie Harrison Dam) is located on Tingalpa Creek. It is managed by Seqwater and forms part of the South East Queensland Water Grid that provides water for Redland City Council suburbs. It is currently an un-gated* dam - this means when rainfall in the catchment results in inflows that increases the water level beyond the Full Supply Level, water flows over the dam spillway. There are no environmental releases / flows. There is no fishway and the dam presents a barrier to fish migration during baseflow conditions, with migration during extreme flood conditions only. Water for the Redland City Council area is supplied by the South East Queensland Water Grid, including supplies from Leslie Harrison Dam and North Stradbroke Island groundwater via a pipe to Heinemann Road Reservoir. The catchment has a large number of rural water storages and weirs (including farm dams), which also modify water flows. Relic and operational weirs often limit tidal extent. Looking downstream from the Leslie Harrison Dam wall - provided by Seqwater. Main photo. Looking across the Leslie Harrison Dam wall - provided by Seqwater. *In 2014, the Full Supply Level of Leslie Harrison Dam was lowered to 53% and the spillway gates removed as part of Seqwater's Dam Improvement Program. During 2015-16, Seqwater undertook a detailed review of Leslie Harrison Dam, including an options study and concept design. During 2017-18, Seqwater will select a design option and finalise the detailed design for the Dam Improvement Project at Leslie Harrison Dam and undertake further studies throughout 2017 to confirm the priority of the upgrade to the dam within the Dam Improvement Program. In the interim, the level of the dam will remain lowered and the spill gates removed. The lowering and removal of the dam gates allows Seqwater to continue to operate the dam safely while investigations into the detailed design continue. Modified features—sedimentIncreases in the volume and speed of run-off can increase erosion in the landscape and the stream channels, resulting in sediment being carried downstream and reduced water quality. Urban run-off impacts most areas, particularly erosion and sedimentation. There is erosion downstream of developments on Coolnwynpin, Thornlands and Eprapah creeks, and stabilisation works have been undertaken in several areas. Main photo. Creek bank re-vegetation and stabilisation using Lomandra sp. - provided by SEQ Catchments. Water qualityWater quality is influenced by point source inputs and diffuse run-off. Water quality is more influenced by point source inputs during dry, low-flow conditions. Point source inputs are sewage treatment plants, septic tank seepage and licensed industrial discharges. There are sewage treatment plants at Thorneside, Capalaba, Cleveland and Victoria Point. Water quality is more influenced by run-off during wet weather and under storm-flow conditions. The Redland Catchment was rated C+ for overall Environmental Condition in 2015. Estuarine water quality was fair, with Tingalpa Estuary in slightly better condition that Eprapah Estuary due to lower nutrient loads (particularly phosphorus) and higher dissolved oxygen levels. The freshwater creeks are high in sediment and nutrient loads.* Redland City Council reported an overall decline in freshwater water quality between 2013 and 2015. Thornlands, Moogurrapum, Ross and southern Redland Bay creeks received a poor rating. Tarradarrapin, Hilliards, Coolnwynpin and Eprapah creeks received a fair rating. Upper Tingalpa Creek was in good condition and Eprapah Creek improved from poor to fair condition. These results were mostly related to poor ratings for chlorophyll-a, but also total suspended solids, nutrients and dissolved oxygen.** *Healthy Waterways Redlands Catchment Report Card (for current report see links at end of map journal). **Redlands Waterway Recovery Report 2015 (see links at end of this map journal). Water flowWater flows across the landscape into streams and eventually into the major waterways of the catchments (click to see animation). The remaining water either sinks into the ground where it supports a variety of terrestrial and groundwater dependent ecosystems or is used for other purposes. The restricted channels and gullies eventually flatten out to form waterways that meander across the floodplain. They pass through alluvial areas which store and release water, prolonging the time streams flow. Main photo. Flooding of Wallaby Creek at Avalon Road - provided by Redland City Council. The sub-catchmentsA catchment is an area with a natural boundary (for example ridges, hills or mountains) where all surface water drains to a common channel to form rivers or creeks.* Larger catchments are made up of smaller areas, sometimes called sub-catchments. The Redlands Catchment consists of large and small sub-catchments. The characteristics of each sub-catchment are different, and therefore water will flow differently in each one. Wynnum Creek and Manly coastal drainageThe Wynnum Creek and Manly coastal drainage sub-catchments are small and highly developed. The underlying geology is mostly sedimentary rocks with alluvium along with channel. There are also areas of Petrie Formation (basalt) and coastal swamp on the lower-lying parts, however these areas have now been developed. Nearly all vegetation has been cleared and there is virtually no regrowth. Land use is mostly urban residential and associated service and infrastructure, including the Wynnum Golf Club, parks and the Manly Boat Harbour. Manly Boat Harbour is a high tide roost site for wader birds. Run-off is high over the impervious surfaces, and there is the potential for flooding. The upper reaches are often dry (ephemeral), and the reaches downstream of Tingal Road (railway line) are tidal. Water flows up the creeks and drains and over the esplanade on the highest tides of the year. This information is presented for broad indicative purposes based on land forms and it does not indicate where flooding may occur. For detailed flooding maps see local council (links provided at the end of this map journal). Main photo. Urban development at Manly - provided by Department of Environment and Science. Lota CreekThe Lota Creek sub-catchment is underlain by fractured metamorphic rocks, impervious rocks, sedimentary rocks and Petrie formation (basalt), together with alluvium along with channel and low-lying coastal swamp. Land use is mostly urban and rural residential, together with nature conservation and recreation. There are also small areas of grazing on native pastures and horticulture. Nearly all the remnant vegetation has been cleared however there are very large areas of regrowth across the catchment. The sub-catchment includes part of the Moreton Bay Ramsar site. run-off is high over the impervious surfaces, and there is the potential for flooding. Water flows up the creeks and drains and over the esplanade on the highest tides of the year. There is some water infiltration and groundwater recharge in the areas underlain by fractured metamorphics and basalt. There are relatively large areas of mangrove forest and saltmarsh along lower Lota Creek, and wader birds use the old Edgell dam in this area. Upper Tingalpa CreekThe upper Tingalpa Creek sub-catchment is underlain by mostly fractured metamorphic and impervious rocks, together with areas of sedimentary rock. run-off from the less permeable geologies is high and flows mostly into the Tingalpa Reservoir. There are other impoundments across the sub-catchment, including many rural water storages, large impoundments associated with Priest Gully and quarry pits adjacent to upper Tingalpa Creek. Land use is mostly rural residential and nature conservation, together with urban residential, quarrying and farming (poultry, grazing on native pastures, horses, turf and pineapples). Historically there was gold and gem fossicking and shallow mines on the western slopes of Mount Cotton. There are large areas of remnant vegetation along the upper reaches (including Venman Bushland National Park), and most areas that were cleared have since regrown. Tingalpa Creek supports a range of frogs, including the eastern stony creek (Litoria wilcoxii), great barred (Mixophyes fasciolatus) and tusked (Adelotus brevis) frog. Buhot Creek has high natural value, including a locally endemic rainbowfish (Rhadinocentrus ornatus) subspecies that requires specific water quality (tannin-stained with low pH) and aquatic habitat. Magpie geese (Anseranas semipalmata) have been seen near the Mount Cotton Road bridge. There are ephemeral (perched) wetlands along Wallaby Creek. This area is underlain by fractured metamorphic rocks and during high rainfall events there is fast run-off and the potential for flooding. Click the following links to see video of flooding near Avalon Road during a high rainfall event, looking upstream and downstream. Main photos. Venman Bushland National Park (top left) - provided by Department of Environment and Science. Barred frog (top right) - provided by Simon Baltais. Magpie geese (bottom left) and eastern stony frog pair in amplexus - provided by Queensland Government. Videos of Wallaby Creek flooding at Avalon Road - provided by Redland City Council. Lower Tingalpa CreekThe Lower Tingalpa Creek sub-catchment is underlain by large areas of sedimentary rocks, together with impervious rocks in the upper reaches and Petrie Formation (basalt) and coastal swamps on the lower-lying land. There are also large areas of alluvium along the channel. Land use is mostly urban and rural residential, together with associated services and infrastructure (golf course, parks, Greenacres Caravan Park), nature conservation, farming (poultry, grazing and horticulture) and light industry. Nearly all the remnant vegetation has been cleared and there is some regrowth in the upper reaches. The sub-catchment includes part of the Moreton Bay Ramsar site. This sub-catchment is highly developed, and water infiltration and groundwater recharge has been substantially reduced over time. It is characterised by infilling of wetlands and other low-lying land for development, and there are issues with leaching, water quality, voids, subsidence and methane in these areas. Despite the development, Coolnwynpin Creek has high natural value. It supports a locally endemic rainbowfish subspecies that requires specific water quality and aquatic habitat, and there are also protected wallum froglets (Crinia tinnula) along upper reaches and perched wetlands associated with lower reaches. There is good riparian vegetation in reserves, including a Swampbox reserve near Indigiscapes and the Greater Glider Conservation Area. There are estuarine wetlands (including mangroves) up to dam wall on Tingalpa Creek. There are sewage treatment plants (STPs) at Capalaba and Thorneside. Coolnwynpin Creek - provided by Queensland Government. Tarradarrapin CreekThe Tarradarrapin Creek sub-catchment is small, flat and highly developed. It is underlain by mostly sedimentary rocks, with alluvium along the channel and Petrie Formation (basalt) and low-lying coastal swamps near the shoreline. Water infiltration and groundwater recharge has been substantially reduced by urbanisation over time. Run-off over these impervious surfaces is high and the area is prone to flooding. Land use is mostly urban residential (including Aquatic Paradise canal and Sovereign Waters lake developments), together with associated services and infrastructure (parks, sporting fields and schools), rural residential, nature conservation, horticulture and waste treatment. Nearly all the remnant vegetation has been cleared and there is very little regrowth. The Tarradarrapin Wetland is part of the Moreton Bay Ramsar site. Tarradarrapin Creek continues to support the native water rat (Hydromys chrysogaster) and native fish such as carp gudgeons (Hypseleotris spp.). Main photo. Aquatic Paradise canals - provided by Department of Environment and Science. Hilliards CreekThe Hilliards Creek sub-catchment is underlain by mostly sedimentary rocks, with fractured metamorphic and impervious rocks in the upper reaches, and Petrie Formation (basalt) and low-lying coastal swamps further downstream. There is fast run-off over these less pervious geologies, and the potential for flooding. There is some alluvium along the channel in the upper parts of the sub-catchment. Land use is mostly urban and rural residential, together with associated services, infrastructure (hospital) and recreation (parks), nature conservation, farming (poultry, grazing, horticulture, forestry, horses), waste (refuse) treatment and disposal and industry. There has been substantial sub-division and the sub-catchment is currently transitioning from a primarily rural to urban footprint. Most of the remnant vegetation has been cleared however there are large areas of regrowth across the upper reaches. The sub-catchment includes part of the Moreton Bay Ramsar site. There are many rural water storages in this sub-catchment, and they form a string of ponds along the smaller tributaries of upper Hillards Creek. The remains of an early causeway across Hilliards Creek are likely to be associated with fellmongeries or wool washes that operated in the 19th century. Geoff Skinner Reserve is part of the Moreton Bay Ramsar site. Jungle perch are known to inhabit the sub-catchment and platypus may also be found. There is a sewage treatment plant (STP) at Cleveland, which discharges to land and lower Hilliards Creek (near Finucane Road). There are bora rings and scar trees along the creek, together with structures such as bridges and wharves. The creek has been a major source of freshwater for brickworks, sugar mills, sawmills and fellmongeries as well as nearby farms, and a shipping route for small steamers. Recreational use of the Geoff Skinner Reserve foreshore - provided by Redland City Council. Ross and Thornlands creeksThe Ross and Thornlands creeks sub-catchments are underlain by mostly sedimentary rocks and Petrie Formation (basalt), with fractured metamorphic and impervious rocks in the upper reaches and low-lying coastal swamps along the shoreline. There is some alluvium in the Thornlands area. Land use is mostly urban (including the Raby Bay marina and canals and Crystal Waters lake developments) and rural residential, together with associated services (hospital), infrastructure and recreationl (parks) and nature conservation. There is also a range of farming (grazing on native pastures, poultry, flowers, fruits and other horticulture) in the Thornlands area and manufacturing and industry in the Ross Creek area. Most of the remnant vegetation has been cleared however there are areas of regrowth across the southern parts. The sub-catchment includes part of the Moreton Bay Ramsar site. Black Swamp is a groundwater-dependent wetland adjacent to Shore Street in Cleveland. There is a weir at Shore Street, and a concrete channel at Island Street (William Ross Park), which influence tidal flow. The Thornlands area has lots of impoundments including farm dams and the relatively large Crystal Waters. In some parts there are farm dams on every property (i.e. every 30 to 50 metres along the channel). Historically, farm dams were retained by development in the 1980-90s but more recently they are being in-filled. Magpie geese use dams in the Thornlands area. Aquatic weeds in the Ross Creek area include the declared class 2 pest plant salvinia (Salvinia molesta). Black Swamp, Shore Street, Cleveland - provided by Department of Environment and Science. Main photos. Urban development along Old Cleveland Road, Cleveland (main page), Raby Bay marina and canals - provided by Department of Environment and Science. Eprapah CreekThe Eprapah Creek sub-catchment is underlain by mostly fractured metamorphic rocks in the upper reaches, and sedimentary rocks in the lower-lying areas. There is also Petrie Formation (basalt) and low-lying coastal swamps along the shore, and relatively large areas of alluvium along parts of the channel. run-off is high over these low porosity rock and heavily developed areas, and there is the potential for flooding. Land use is mostly urban and rural residential together with services and infrastructure (parks, recreation and research facility), however there are large areas of nature conservation, grazing on native pastures, other farming (poultry, horses and grape horticulture) and industry (slipway). Much of the remnant vegetation has been cleared however there are large areas of regrowth. The sub-catchment includes part of the Moreton Bay Ramsar site. There are many rural water storages, including at Karingal Scouts, poultry farms, the vineyard and research facility. In some parts there are farm dams on every property. Many wetlands have been in-filled for development. Septic seepage from rural areas and erosion and sedimentation downstream of urban areas affects water quality. The Moreton Bay Ramsar site includes part of lower Eprapah Creek and Egret Wetlands. Lower Eprapah Creek is an important wader bird roost site. Ornate sunfish (Rhadinocentrus ornatus) and the protected native jute (Corchorus cunninghamii) are known from the sub-catchment, together with the declared class 1 pest plant Senegal tea (Gymnocoronis spilanthoides). Upper and mid Eprapah Creek support small populations of the ornate rainbowfish. There is a sewage treatment plant (STP) at Victoria Point. Point Halloran Conservation Area, which is included within the Moreton Bay Ramsar site - provided by Department of Environment and Science. Main photos. Victoria Point ferry terminal servicing Coochiemudlo Island (top left) - provided by Department of Environment and Science. Recreational use of Eprapah Creek, showing sedimentary rock and variety of aquatic habitat (top right) and large Eucalyptus racemosa (bottom left) - both provided by Eprapah Creek Catchment Landcare Association. Farming in the upper catchment (bottom right) - provided by Department of Environment and Science. Moogurrapum CreekThe upper parts of the Moogurrapum Creek sub-catchment are underlain by fractured metamorphic rocks, together with impervious rocks, sedimentary rocks, Petrie Formation (basalt) and low-lying coastal swamps. There are relatively large areas of alluvium along most of the channel. run-off is high over these low porosity rock and heavily developed areas, and there is the potential for flooding. Land use is mostly urban, rural residential and associated services and infrastructure (parks and golf course), together with nature conservation, grazing on native pastures, poultry farming, horticulture, mining and industry. Most of the remnant vegetation has been cleared however there are large areas of regrowth across the upper reaches. The sub-catchment includes part of the Moreton Bay Ramsar site. There are lots of rural water storages, including a relatively large on-stream dam in the headwaters and dams of various sizes at poultry farms. Moogurrapum Creek (Bayview Conservation Park, Days Road) supports native fish (gudgeons) and populations of the world's smallest crayfish (Tenuibranchiurus glypticus). The protected Illidge's ant-blue butterfly (Acrodipsas illidgei) has been collected from mangroves at the creek mouth. Typical wetland habitat of the world's smallest crayfish (Days Road, Redland Bay) - provided by Simon Baltais Southern Redland BayThe Southern Redland Bay sub-catchment includes Weinam and Torquay creeks in the north, together with many unnamed creeks. The sub-catchment is underlain by fractured metamorphic rocks, with Petrie Formation (basalt) and coastal swamps and saltmarsh in the lower-lying areas. There is alluvium along most of the channels. Run-off is high over these low porosity rock and heavily developed areas, and there is the potential for flooding. Land use is mostly urban, rural residential and grazing on native pastures, together with other farming (horticulture, cropping and poultry) and nature conservation. Rural properties are serviced by septic systems. Most of the remnant vegetation has been cleared however there are areas of regrowth. The sub-catchment includes part of the Moreton Bay Ramsar site. There are perched wetlands across the sub-catchment, on the alluvium underlain by less porous rocks. Large farm dams provide habitat for waterbirds, and the protected lesser swamp orchid (Phaius australis) is found in reserves. Other natural features of this sub-catchment include the Orchard Beach Wetlands and Foreshore. ConclusionThe Redlands Catchment shows how natural and modified features within the landscape impact on how water flows. These issues need to be managed to ensure that the significant natural (and social) values of the catchment are protected, and to minimise impacts on the multitude of values within the catchment and Moreton Bay, while providing for residential, farming and other important land uses of the catchment. Knowing how the catchment functions is also important for future planning, including climate resilience. With this knowledge, we can make better decisions about how we manage this vital area. Main photos. Residential jetties near Cleveland Point (top left), Farming in upper Eprapah Creek sub-catchment (top middle), Point Halloran Conservation Area, Victoria Point (top right), Cleveland Point Park (middle left), Urban development at Manly (middle), Tingalpa Reservoir (middle right), Boats moored at Victoria Point (bottom left), Raby Bay Marina (bottom middle), Venman National Park (bottom right) - all provided by Department of Environment and Science. AcknowledgementsDeveloped by the Queensland Wetlands Program in the Department of Environment and Science in partnership with: Council of Mayors South East Queensland Healthy Waterways (Healthy Waterways and Catchments) Australia and New Guinea Fishes Association – Queensland Inc Eprapah Creek Catchment Landcare Association Quandamooka Yoolooburrabee Aboriginal Corporation This resource should be cited as: Walking the Landscape – Redlands Catchment Map Journal v1.0 (2016), presentation, Department of Environment and Science, Queensland. Photos provided by: Redland City Council, Healthy Waterways, SEQ Catchments, Eprapah Creek Catchment Landcare Association and Simon Baltais. The Queensland Wetlands Program supports projects and activities that result in long-term benefits to the sustainable management, wise use and protection of wetlands in Queensland. The tools developed by the Program help wetlands landholders, managers and decision makers in government and industry. Contact wetlands♲des.qld.gov.au or visit wetlandinfo.des.qld.gov.au Disclaimer:This map journal has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within the document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this education module is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. Data sources, links and informationSoftware Used ArcGIS for Desktop | ArcGIS Online | Story map journal Some of the information used to put together this map journal can be viewed on the QLD Globe. The Queensland Globe is an interactive online tool that can be opened inside the Google Earth™ application. Queensland Globe allows you to view and explore Queensland spatial data and imagery. You can also download a cadastral Smartmap or purchase and download a current titles search. More information about the layers used can be found here: Flooding Information: Redland City Council; Logan City Council Other References City of Gold Coast (2021) About water catchments. [webpage] Accessed 25 August 2021 Healthy Waterways (2016), Redlands Catchment 2015 Report CardRedlands Catchment 2016 Report Card. [webpage] Accessed 14 June 2016.Queensland Government (2016) Regional Ecosystems [webpage] Accessed 12 October 2016. Redland City Council (2015) Annual Waterway Recovery Report 2015, Redland City Council. BOM (2016) Climate Data Online [webpage] Accessed 24 August 2016. Last updated: 25 August 2021 This page should be cited as: Department of Environment, Science and Innovation, Queensland (2021) Redlands Catchment Story, WetlandInfo website, accessed 8 May 2025. Available at: https://wetlandinfo.des.qld.gov.au/wetlands/ecology/processes-systems/water/catchment-stories/transcript-redlands.html |

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation