|

|

Pine Catchment StoryThe catchment stories use real maps that can be interrogated, zoomed in and moved to explore the area in more detail. They take users through multiple maps, images and videos to provide engaging, in-depth information. Quick facts

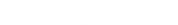

Quick linksTranscriptUnderstanding how water flows in the catchmentTo effectively manage a catchment it is important to have a collective understanding of how the catchment works. This map journal gathers information from experts and other data sources to provide that understanding. The information was gathered using the ‘walking the landscape’ process, where experts systematically worked through a catchment in a facilitated workshop, to incorporate diverse knowledge on the landscape features and processes, both natural and human. It focused on water flow and the key factors that affect water movement. The map journal was prepared by the Queensland Wetlands Program in the Queensland Department of Environment and Science in collaboration with local partners. Main image. Lake Samsonvale - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. How to view this map journalThis map journal is best viewed in Chrome or Firefox, not Explorer.

Please note that the use of the terms 'Catchment' and 'Basin' are sometimes used interchangeably. In this map journal the term 'Catchment' has been used. Map journal for the Pine Catchment—water movementThis map journal describes the location, extent and values of the Pine Catchment. It demonstrates the key features which influence water flow, including geology, topography, rainfall and runoff, natural features, human modifications and land uses. Knowing how water moves in the landscape is fundamental to sustainably managing the catchment and the services it provides. The South Pine River at Eatons Hill - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. Pine Catchment StoryThe Pine Catchment is located to the north of Brisbane with headwaters in the D’Aguilar Range (Mount Glorious and Mount Nebo). It falls mostly within the Moreton Bay Regional Council boundary but also includes part of Brisbane City Council area. The catchment covers approximately 825 square kilometres. There are approximately 1,770 kilometres of stream network, with 17 kilometres defined as estuarine (click for animation). The main waterways are the North and South Pine rivers, together with numerous smaller waterways including Hays Inlet. The South Pine River joins the larger North Pine River near Murrumba Downs to form the Pine River, which joins Hays Inlet and flows into northern Moreton Bay. The Caboolture Catchment is located to the north, with the Stanley Catchment to the north-west, and the broader Brisbane catchments to the west and south. Main image. Rural development near Dayboro showing sewage treatment plant (centre) and D'Aguilar Range (background) - provided by Unitywater. Values of the catchmentThe Pine Catchment contains many environmental, economic and social values. The catchment includes the townships of Dayboro, Mount Glorious, Samford Valley and Clear Mountain and the urbanised areas of the lower catchment. The lower half the catchment is mostly residential (rural* and urban). There has been substantial development over time across coastal areas (click to see interactive swipe map showing changes in development over time - zoom to an area of interest).** Most of the upper catchment is used for grazing on native pastures (cattle)*** and nature conservation, together with small areas of other farming and mining/quarrying. There are several protected areas across the catchment, including the D’Aguilar National Park. The catchment also includes public nature refuges, Hay’s Inlet Fish Habitat Area, and parts of the Moreton Bay Ramsar site and Moreton Bay Marine Park. Main images. North Pine Dam wall (top left); Hay's Inlet mangroves (middle left); Dayboro rural development and sewage treatment plant, with D'Aguilar Range in the background (top right); pineapple farm at Samsonvale (bottom middle); Strathpine urban development (bottom right) - provided by Unitywater. Horse property along the South Pine River, Leitchs Road South (bottom left) - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. *Please note the residential areas shown include rural residential as well as other residential area types. **This application may take time to load. ***Grazing is mapped as ‘grazing on native pastures’ when there is a substantial native species component, despite extensive active modification or replacement of native vegetation. If there is greater than 50 per cent native pastures then the area is classified as ‘grazing on native pastures’. If there are no native species, the area is classified as ‘grazing on modified pastures (see links at the end of this map journal for further information regarding land use management classification). Values of the catchment—economicUrban development and residential living are strong drivers of the local economy. Fertile soils support grazing (mostly on native pastures) together with horticulture (including pineapple, mangoes, strawberries and turf), irrigated cropping, forestry and intensive animal husbandry (including dairies and horse studs). There is mining and quarrying scattered across the catchment, including hard rock and gravel and sand key resource areas.* Main image: Pineapple farm at Samsonvale with D'Aguilar Range in the background - provided by Unitywater. *Please note sand and hard rock extraction shown are within KRA (Key Resource Areas) only. KRAs are identified locations containing important extractive resources of state or regional significance worthy of protection for future use. Some KRAs include existing extractive operations (see link at end of map journal for more information). Values of the catchment—environmental and socialThe catchment contains a number of protected areas, with the largest being D’Aguilar National Park. The wetlands and creeks of the catchment provide habitat for many important aquatic species, including plants, frogs, migratory birds and platypus. There are several areas in the upper catchment with high aquatic biodiversity as identified by Moreton Bay Regional Council* and the state government (as indicated by dark blue creek lines, see legends).** Estuarine areas support important marine plant (mangrove, saltmarsh and seagrass) and fisheries species. Protected areas also provide recreational activities, such as bush walking, bird watching, four wheel driving, camping and kayaking. These activities not only provide substantial social and health benefits but they are also very important for tourism. Information about the different types of wetlands shown in this mapping is provided here. Main image: Recreational use of the South Pine River at Bunya Park - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. *Nolte, U. (2013) Freshwater Streams Monitoring in Moreton Bay Region, Scarborough (see links at end of this map journal). **Department of Environment and Science (2013) Aquatic Conservation Assessment Series (see links at end of this map journal). Values of the catchment—environmental and socialNorth Pine Dam (Lake Samsonvale) is one of the 12 key water supply storages for South East Queensland. It is managed by Seqwater and forms part of the South East Queensland Water Grid, which supplies water to Moreton Bay Regional Council areas. Water is extracted at the dam wall and treated at the water treatment plant on-site. The catchment upstream of North Pine Dam is influenced by the underlying geology, topography and surrounding and upstream land uses (farming, residential areas and other intensive land uses such as quarrying and mining). This can result in periods of poor water quality that challenge the treatment capabilities of the water treatment plant. There is also a dam on Sideling Creek (Lake Kurwongbah), which is currently used for water supply. Groundwater is extensively used throughout the catchment, which means that there are many bores, particularly across the mid catchment. The water from these bores are extracted for livestock and domestic purposes. Groundwater is also extracted from the river alluvium to supply the standalone water treatment plant at Dayboro for the Dayboro community. *DNRM bore mapping. Main image: Lake Samsonvale - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. Natural features—geology and topologyThe upper catchment is underlain by large bands of several different types of metamorphic rock, which provide for some local groundwater recharge through fractures. There are several springs. The sedimentary rock across the catchment has relatively low groundwater recharge potential, and provides for fast surface water runoff, especially where the landforms are steep. Large alluvial deposits in the channels enable water infiltration and recharge of groundwater, and support substantial wetland development. There are large areas of alluvium downstream of Dayboro and upstream of the confluence of the North Pine and South Pine rivers, and other unconsolidated sediments in the estuarine reaches formed by coastal processes. There are also areas of impervious rock across the catchment, and a small area of basalt in the Cedar Creek headwaters. These different rock types combine to make up the geology of the Pine Catchment. Main image: Rocky substrate along Cedar Creek - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. Natural features—rainfallThere is high rainfall across most of the catchment, with slightly higher rainfall in parts of the upper catchment. These different rainfall levels combine to make up the rainfall of the Pine Catchment. Natural features—pre-clearing vegetationVegetation affects how water flows through the catchment, and this process is affected by land use and management practices. Native vegetation slows water, retaining it longer in the landscape and recharging groundwater aquifers, and reducing the erosion potential and the loss of soil from the catchment. Historically, most of the catchment supported eucalypt woodlands and open forests. There were large areas of rainforests and scrubs (including sub-tropical lowland rainforest) in the upper and mid catchment, and areas of wet eucalypt forest in the headwaters. In the lower catchment there were large areas of melaleuca woodlands, together with eucalypt vegetation, mangrove and saltmarsh and other coastal communities including heaths. These different vegetation types combine to make up the preclearing vegetation of the Pine Catchment. Main image. Eucalypt vegetation with cat's claw creeper at Clear Mountain, showing the North Pine Dam (background) - provided by Unitywater. *Broad Vegetation Groups derived from Regional Ecosystems. Regional Ecosystems are vegetation communities in a bioregion that are consistently associated with a particular combination of geology, landform and soil. Modified features—vegetation and land useApproximately half the catchment has been cleared for a range of urban and rural land uses (particularly grazing on native pastures and residential*). Eucalypt vegetation, and rainforests and scrubs remain across much of the upper catchment, however large areas of rainforests and scrubs have been cleared along the upper North Pine River. Large areas of melaleuca woodland and other coastal communities including heath have been cleared from the lower reaches, however mangrove forest still lines the lower reaches. A range of different land use types combine to make up the land use of the Pine Catchment.** Re-vegetation along upper Bells Creek - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. *Please note the rural residential areas shown include rural residential as well as other residential area types. **See links at end of this map journal for further details regarding land use classification. Modified features—vegetation clearingApproximately half the catchment has been cleared. Large areas of vegetation have regrown* since initial clearing. Explore the swipe map using either of the options below.**

These developments and activities change the shape of the landscape and can modify water flow patterns. *Please note this regrowth includes non-native vegetation. **Please note this application takes time to load. Modified features—channels and infrastructureBuildings and important infrastructure such as roads, railways and creek crossings create barriers and impermeable surfaces that redirect water through single points or culverts, leading to channelling of water. This increases the rate of flow and the potential for erosion. The lower reaches have been heavily developed and there are many barriers and impermeable surfaces. Modifications to channels, such as straightening and diversions, can also increase flow rates. Infrastructure can also affect fish passage, and several barriers are known to affect fish passage in the Pine Catchment.* Main image. Railway crossing of the North Pine River at A.J. Wylie Park - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. Linked image. Erosion upstream of the railway crossing of the North Pine River - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. *Catchment Solutions (2016) Greater Brisbane Urban Fish Barrier Prioritisation Process, Brisbane (see links at end of map journal). Modified features—dams and weirsDams and weirs also modify the natural water flow patterns, by holding water. The catchment has two large dams and they influence how and when water flows through parts of the catchment. North Pine Dam (Lake Samsonvale) is the largest water storage and is mainly used for urban water supply via the South East Queensland Water Grid. It has five radial gates that can be used to release water during times of heavy rain. Sideling Creek Dam (Lake Kurwongbah) is used for water supply to the Petrie water treatment plant, and for recreation, including picnicking, waterskiing, rowing and fishing from paddle craft and the shore. It is un-gated and operates at a reduced water level* as an overflow dam with no environmental releases/flows. The catchment has numerous rural water storages and weirs, together with stormwater retention basins in urban areas. These structures also modify water flows. *As at March 2017, the dam was operating at a reduced water level as part of the Dam Safety Program (by way of a 2 by 2 metre opening in the spillway to reduce the full supply level of the lake by 2 metres to about 60% capacity). Main image: North Pine Dam wall - provided by Unitywater. Modified features—sedimentIncreases in the volume and speed of runoff can increase erosion in the landscape and the stream channels, resulting in sediment being carried downstream and reduced water quality. There was localised erosion and sedimentation associated with extreme rainfall events during 2011 and 2013, including along Russell Family Park (upper South Pine River), Camp Mountain (Samford Creek), Wongan Creek, and Strathpine (South Pine River). There is also erosion and sedimentation in estuarine areas subject to boat wash (the lower South Pine River and Pine River mouth) and pedestrians/fishers (Tinchi Tamba Wetlands). There was large scale erosion along the North Pine River above Lake Samsonvale during the 2013 flood, which fundamentally changed the river hydrogeology. For example an avulsion cut-off an existing meander downstream of the Terrors Creek confluence. This has led to a large headcut and substantial lower of the channel bed, which in turn affects water quality, flows (water availability) and infrastructure in some areas. Sedimentation in Saltwater Creek, North Lakes - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. Main images: Erosion along Wongan Creek - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. Figure showing changes to North Pine River downstream of the Terrors Creek confluence - provided by Seqwater. Water qualityWater quality is currently influenced by runoff and point source inputs such as sewage treatment plants, seepage from on-site wastewater systems (e.g. septic tanks) and stormwater discharge. There are sewage treatment plants (STPs) at Dayboro, Murrumba Downs, Brendale and Redcliffe. During 2016, Healthy Waterways graded the overall Environmental Condition Grade of the Pine Catchment as B-. Pollutant loads significantly improved from very high to very low in freshwater reaches. Estuarine water quality improved from fair to excellent due to improved dissolved oxygen and water clarity conditions in parts of the estuary. However, phosphorus concentrations continue to exceed guidelines throughout the estuary.* As at March 2015, freshwater water quality and stream health at council sites was variable and tended to decrease with distance downstream.** *Healthy Waterways Pine Catchment Report Card (for current report see links at end of map journal). **Nolte, U. (2013) Freshwater Streams Monitoring in Moreton Bay Region, Scarborough (see links at end of this map journal). Stream health is determined by assessing water quality (physical, chemical and concentration of potential contaminants) and macroinvertebrates (species composition, community structure and presence of high biodiversity species). Water flowWater flows across the landscape into streams and eventually into the Pine River (click to see animation*). The remaining water either sinks into the ground where it supports a variety of terrestrial and groundwater dependent ecosystems or is used for other purposes. The restricted channels and gullies eventually flatten out to form waterways that meander across the floodplain. They pass through alluvial areas which store and release water, prolonging the time streams flow. The South Pine River is one of the few remaining subcatchments in South east Queensland that does not have major barrier to water movement. Anabranch of the lower South Pine River, Albany Creek (James Cash Court) - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. *Please note this application takes time to load. The subcatchmentsA catchment is an area with a natural boundary (for example ridges, hills or mountains) where all surface water drains to a common channel to form rivers or creeks.* Larger catchments are made up of smaller areas, sometimes called subcatchments. The Pine Catchment consists of large and small subcatchments. The characteristics of each subcatchment are different, and therefore water will flow differently in each one. *Definition sourced from the City of Gold Coast website (see links at the end of this map journal). North Pine River to dam wallThe headwaters of the North Pine River are steep, flow through the D’Aguilar National Park, and receive very high rainfall over mostly fractured metamorphic rocks. Surface water runoff is high and creek flow is fast. Fractures in the metamorphic rocks and alluvium in the channel provide for some local groundwater recharge. The headwaters within D’Aguilar National Park, and other slopes and ridges, are still largely vegetated. There are areas of black melaleuca-dominated vegetation upstream of Brisbane Road, and rainforests and scrubs (including sub-tropical lowland rainforest) between Brisbane Rd and the dam. Large areas of lower lying land have been cleared for grazing on native pastures, together with dairying, horticulture and rural residential. Some of the cleared vegetation has regrown. North Pine Dam (Lake Samsonvale) influences water flow and there are also many farm dams in the upper reaches. Lake Samsonvale is surrounded by land that is protected to ensure water quality in the dam is maintained, together with utilities (power line easement) and recreation, and nearby rural residential, grazing on native pastures, horticulture and mining(part of two hard rock Key Resource Areas). The dam is fitted with a fishway and controlled water releases (environmental flows) are managed to facilitate migration of the protected lungfish. Lake Samsonvale is popular for picnicking and used for fishing and boating. Main image: Mount Samson Road crossing of the North Pine River - provided by Unitywater. Laceys Creek subcatchmentThe headwaters of Laceys Creek are steep, flow through the D’Aguilar National Park, and receive high rainfall over fractured metamorphic rocks. Surface water runoff is high and creek flow is fast. Fractures in the metamorphic rocks and alluvium in the channel provide for some local groundwater recharge. There are perched aquifers and water travels through gravel under the stream bank (hyporheic flow) in parts of this subcatchment. The headwaters within D’Aguilar National Park, and other slopes, are still largely vegetated. The lower lying parts of the subcatchment have been cleared for grazing on native pastures, together with rural residential, horticulture and irrigated cropping. Some vegetation has regrown since initial clearing. Cattle and septic seepage are impacting the waterways in some areas. Gravel has been extracted from some of the lower channels. Terrors Creek subcatchmentThe headwaters of Terrors Creek are steep and receive high rainfall over fractured metamorphic rocks. Surface water runoff is high, creek flow is fast and mostly permanent in the main channel. Fractures in the metamorphic rocks and alluvium in the channel provide for some local groundwater recharge. Most of the subcatchment has been cleared for grazing on native pastures and rural residential and associated services, together with horticulture. Some vegetation remains on the slopes and there are large areas of regrowth. Camphor laurel is damaging banks in some areas. There has been major flooding at Dayboro, where three tributaries converge at a constriction point. There is a 'perched subcatchment' above a waterfall in the north of the subcatchment. This area drains from the adjacent range and there is fast flow, with the channel dropping approximately 200 metres over a distance of 500 metres. There is a sewage treatment plant at Dayboro, which releases to land. Main images: Looking west from Dayboro to the D'Aguilar Range (top left); Grazing near Dayboro (top right); Strong Road culvert crossing of Terrors Creek (bottom left); Dayboro town centre (bottom middle) - provided by Unitywater. Flooding in Dayboro (bottom right) - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. Kobble Creek subcatchment including Mount Samson CreekThe headwaters of Kobble Creek are steep, flow through the D’Aguilar National Park, and receive high rainfall over mostly fractured metamorphic rocks. Mount Samson Creek also receives high rainfall and is underlain by mostly impervious rocks, however it is less steep. Fractures in the metamorphic rocks and large areas of alluvium along Mount Samson Creek and lower Kobble Creek provide for some local groundwater recharge. Water flows through sand under the stream bank (hyporheic flow) along parts of Mount Samson Creek. The headwaters and slopes of Kobble Creek are largely vegetated. Most of the lower lying areas, and nearly all of Mount Samson Creek, have been cleared for grazing on native pastures and rural residential and associated services, together with horticulture and horses. Residential development is currently increasing at Mount Samson. There are large areas of vegetation regrowth, including black melaleuca-dominated vegetation in the mid reaches. Water movement is slow across the lower lying parts of these subcatchments, with the potential for flooding around the construction point at Mount Samson. North Pine Dam (Lake Samsonvale) influences water flow. There are also many farm dams on the lower lying land across these subcatchments. Lake Samsonvale is surrounded by land that is protected to ensure water quality in the dam is maintained. There are also recreational areas and nearby rural residential, grazing on native pastures and horticulture. North Pine River from dam wall to M1 including Yebri Creek subcatchmentThe North Pine River (from dam wall to M1) and Yebri Creek subcatchments are underlain by mostly fractured metamorphic rocks with large areas of alluvium in the channel. Fractures in the metamorphic rocks and alluvium provide for some local groundwater recharge. Most of the area has been cleared for urban and rural residential, together with associated services, manufacturing and industry, grazing on native pastures and mining (including gravel and sand Key Resource Areas). Vegetation remains in conservation areas and some vegetation has regrown since initial clearing. Mangrove forests* line the lower reaches and there is a small patch of rainforests and scrubs on the southern bank. The river moves very slowly and it can take 25 days to move from A. J. Wylie bridge to the mouth. The northern bank can flood after water release from the dam, including Gympie Road and the railway line. The southern bank is steep with some scours/erosion. There are boat wash issues and erosion at Castle Hill and near Mungara Reserve. There are several large water bodies along the North Pine River, associated with historic sand mining, including Black Duck Creek dams. There is a sewage treatment plant at Murrumba Downs. *mostly Avicennia marina, together with Rhizophora stylosa, Excoecaria agallocha and Aegiceras corniculation and saltmarsh. Main images: Aerial photo looking down the North Pine River in 2010, showing Murrumba Downs sewage treatment plant and large water bodies (top left); Gympie Road (top right) and railway crossing (bottom middle) of the North Pine River; residential development along the North Pine River (bottom right) - provided by Unitywater. Flooding at Youngs Crossing (bottom left) - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. Sideling and Whiteside creeks subcatchmentsThe headwaters of Sideling and Whiteside creeks are steep and receive high rainfall over mostly fractured metamorphic rocks. There are large areas of alluvium along Sideling Creek. Fractures in the metamorphic rocks and alluvium provide for some local groundwater recharge. Approximately half the subcatchments have been cleared for grazing on native pastures and rural residential, together with associated services, utilities, horticulture and mining (part of four gravel and sand Key Resource Areas). Some vegetation remains, particularly on the southern slopes of Sideling Creek. Cleared vegetation in Whiteside Creek subcatchment has almost completely regrown. Sideling Dam (Lake Kurwongbah) influences water flow and there are also many farm dams in this subcatchment. Lake Kurwongbah is a popular recreational area and surrounded by land that is protected to ensure water quality in the dam is maintained, together with services and recreation, rural residential, grazing on native pastures and nearby horticulture. The dam is not presently fitted with a fishway and is a barrier to fish passage. The extent of tidal water is typically between Young’s Crossing and the A. J. Wylie Bridge. The North Pine River can back up into Whiteside Creek, particularly with large tidal input and this can increase during major flood events. There can be localised flooding when the dam releases water, including Young’s Crossing. One Mile Creek and Todds Gully subcatchmentsThe One Mile Creek and Todds Gully subcatchments are underlain by mostly fractured metamorphic rocks and impervious rocks. There are large areas of alluvium in the lower parts, and Todds Gully is prone to flooding due to backing up of the North Pine River. Historically there was good groundwater recharge in these subcatchments but this has been reduced by development and hard surfaces. All of Todds Gully and most of One Mile Creek have been cleared for urban and rural residential, together with services and recreation, utilities, grazing on native pastures, mining, horticulture and waste treatment (refuse). Some vegetation remains, mostly within the Clear Mountain Forest Reserve. Four Mile, Conflagaration and Coulthards creeks subcatchmentsThese subcatchments are underlain by mostly impervious rocks, together with fractured metamorphic rocks and unconsolidated sediments. There are large areas of alluvium in the lower parts, and these areas are prone to flooding. Fractures in the metamorphic rocks and alluvium provide for some local groundwater recharge. Nearly all of these subcatchments have been cleared for urban and rural residential, together with associated services and recreation, grazing on native pastures, utilities, mining, manufacturing and industry and irrigated cropping. Some vegetation remains, mostly in recreation and conservation areas. Historic land uses include landfill at the Four Mile Creek mouth, and brickworks and feedlots on Coulthard Creek. Many of the channels are concrete-lined in the lower reaches, and there are also detention basins. There is bank erosion along Coulthards Creek at Strathpine. Main images: Strathpine shopping centre (top left); Conflagaration Creek, with railway crossing in the background (top middle) - provided by Unitywater. Lower Four Mile Creek, upstream of Bells Pocket Road (bottom left); Old North Road crossing of Four Mile Creek (right) - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. Linked image: Sporting fields on historic landfill site near Four Mile Creek mouth - provided by Unitywater. South Pine River subcatchmentThe headwaters of the South Pine River are steep, flow through the D’Aguilar National Park, and receive high rainfall over fractured metamorphic rocks. The lower reaches are underlain by impervious rocks, sedimentary rocks and unconsolidated sediments, with large areas of alluvium upstream of the confluence with the North Pine River. Surface water runoff is high and creek flow is fast. Fractures in the metamorphic rocks and alluvium provide for some local groundwater recharge. Water travels through gravel under the stream bank (hyporheic flow) in the upper parts. The headwaters within D’Aguilar National Park and Samford Conservation Park are still largely vegetated, and rainforests and scrubs (including sub-tropical lowland rainforest) remain along much of the main channel. Most other areas have been cleared for urban and rural residential, together with associated services and recreation, grazing on native pastures, horticulture, manufacturing and industry, turf farming and mining (part of four gravel and sand Key Resource Areas). Much of the cleared vegetation has regrown since initial clearing. Some banks are eroded due to historic sand mining, intense rainfall (Russell Family Park) and boat wash (Strathpine). There is revegetation by council and community groups, and construction of a fishway has been approved at Leitchs Crossing, Brendale. There are many farm dams on the lower lying land. Platypus are known to occur in the subcatchment. There is a sewage treatment plant at Brendale, with treated water used to provide environmental flows for the river. Samford and urban areas are sewered, however most rural areas use septic tanks. Tidal water typically extends to Strathpine Road (Pine Rivers Park/Lawton Park). Main images: Utility crossings of the South Pine River at Cribb Road, Brendale (top left); Samford Valley looking from Eatons Crossing Road (top right); Cash's Crossing (bottom left) and railway crossing (bottom right) of the South Pine River - provided by Unitywater. The South Pine River at Eatons Hill (bottom middle) - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. Samford, Bergin, Wongan, Kingfisher, Sandy and Albany creeks subcatchmentsMost of these subcatchments have steep headwaters that receive high rainfall over fractured metamorphic rocks. The lower reaches of Sandy and Albany creeks are underlain by sedimentary rocks and impervious rocks. There are large areas of alluvium and the potential for flooding at Samford Village, where there is a geology constriction point at the confluences of the smaller waterways with the South Pine River.The headwaters within the D’Aguilar National Park and Bunyaville and Samford conservation areas are still vegetated. Most of the remaining areas have been cleared for urban and rural residential, together with associated services and recreation, grazing on native pastures, waste treatment (refuse) and horticulture. Small patches of rainforests and scrubs (including sub-tropical lowland rainforest) remain along parts of Samford Creek and there are large areas of regrowth across the Samford, Bergin and Wongan creeks subcatchments. A historic landfill site has been converted to sporting fields at the top of Kingfisher Creek. Samford and urban areas are sewered, whereas most rural areas use septic systems. There are farm dams in most subcatchments. Water monitor at Mahaca Park, Albany Creek - provided by Unitywater. Main images: Samford Creek (top left); Wongan Creek culvert crossing (bottom middle); Bergin Creek rock-lining (bottom right) - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. Main Street crossing of Samford Creek, Samford Village (top right); Samford Village town centre (bottom left) - provided by Unitywater. Cedar Creek subcatchmentThe headwaters of Cedar Creek are steep, flow through the D’Aguilar National Park, and receive high rainfall over fractured metamorphic rocks, impervious rocks and basalt. The lower reaches are underlain by fractured metamorphic rocks and there is alluvium along much of the main channel. Areas of basalt, fractured metamorphic rocks and alluvium provide for some local groundwater recharge.The headwaters within the D’Aguilar National Park, and adjacent slopes and ridges, are still vegetated. Rainforests and scrubs (including sub-tropical lowland rainforest) remain along most of the main channel. Large areas of lower lying land have been cleared for rural residential, together with associated services and recreation, grazing on native pastures and horticulture. Much of the cleared vegetation has since regrown. There are many farm dams. Platypus and freshwater crayfish are known to occur in the subcatchment. Lower Cedar Creek - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. Main image. Rocky substrate, upper Cedar Creek - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. Griffin and Bald Hills creeks, and the Pine River mouth subcatchmentsThese subcatchments are underlain by sedimentary rocks, alluvium and unconsolidated sediments, together with fractured metamorphic rocks and sand. The alluvium, sand, other unconsolidated sediments and fractured metamorphic rocks provide for some local groundwater recharge. Most of Griffin and Bald Hills creek subcatchments have been cleared for urban and rural residential, together with associated services and recreation, grazing on native pastures, horticulture and irrigated cropping. Relatively large areas of estuarine wetlands including mangroves and saltmarsh remain, including Tinchi Tambi Wetlands, together with several palustrine and lacustrine wetlands. There are smaller areas of melaleuca, eucalypt and other coastal communities including heath. Some of the vegetation has regrown since initial clearing, particularly along the edge of the mangroves. Sandbars across the mouth of the Pine River tend to reduce flow and this area is prone to storm tide flooding. There is some erosion, particularly on the north side of the mouth where mangroves have been undercut.These subcatchments include part of the Hay’s Inlet* Fish Habitat Area and the Moreton Bay Ramsar site and marine park. The Griffin Creek subcatchment also includes part of Hay’s Inlet Conservation Park 1. Spanner crabs, dolphins, mullets, prawns are known to occur around the mouth. There are recreational and commercial fisheries around the mouth. The North Pine River (10 kilometres ATMD) - provided by Unitywater. *The Hay’s Inlet protected areas are discussed further on the Hay’s Inlet slide. Main image: The North Pine River at Deep Water Bend, looking south west - provided by Unitywater. Linked image. Flooding along Dohles Rocks Road - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. Freshwater Creek subcatchmentThe Freshwater Creek subcatchment is underlain by sedimentary rocks with alluvium in the channels, together with other unconsolidated sediments and a small area of fractured metamorphic rocks. The alluvium, other unconsolidated sediments and fractured metamorphic rocks provide for some local groundwater recharge.Relatively large areas of estuarine wetlands including mangroves and saltmarsh remain, together with smaller areas of melaleuca, eucalypt and other coastal communities including heath. There are also palustrine and lacustrine wetlands across the subcatchment. Some of the vegetation has regrown since initial clearing, particularly along the edge of mangroves. There are several farm dams across the subcatchment, including relatively large on-stream impoundment on tributaries. However, east of the M1 there are good freshwater and estuarine connections to Hay’s inlet. This subcatchment include part of the Hay’s Inlet* fish habitat area and conservation parks, and the Moreton Bay Ramsar site and marine park. *The Hay’s Inlet protected areas are discussed further on the Hay’s Inlet slide. Saltwater Creek subcatchmentThe Saltwater Creek subcatchment is underlain by sedimentary rocks with alluvium in the channels, together with other unconsolidated sediments. The alluvium and other unconsolidated sediments provide for some local groundwater recharge.Most of the this subcatchment has been cleared for urban and rural residential, together with associated services, recreation (golf course), manufacturing and industry (including heavy industry), grazing on native pastures, horticulture, irrigated cropping, waste treatment, poultry and mining. Relatively large areas of estuarine wetlands, including mangroves and saltmarsh, remain together with smaller areas of melaleuca and eucalyptus vegetation. There are large areas of regrowth in the upper subcatchment and also along the landward edge of mangroves. There is also several palustrine and lacustrine wetlands across the subcatchment, including surface and groundwater-fed wetlands. This creek has permanent flow. There are several impoundments across the subcatchment, including historic pineapple farm dams. However most impoundments are off-stream and there are good connections to Hays Inlet. This subcatchment include part of the Hay’s Inlet* fish habitat area and conservation parks, and the Moreton Bay Ramsar site and marine park. Native water rats are known to occur in the subcatchment. *The Hay’s Inlet protected areas are discussed further on the Hay’s Inlet slide. Sedimentation in Saltwater Creek, near North Lakes - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. *The Hay’s Inlet protected areas are discussed further on the Hay’s Inlet slide. Hay’s Inlet subcatchmentThe Hay's Inlet subcatchment is underlain by mostly unconsolidated sediments, together with impervious rocks and alluvium. The alluvium and other unconsolidated sediments provide for some local groundwater recharge.The eastern section of this subcatchment has been cleared for urban residential, together with associated services and recreation (golf course), manufacturing and industry and waste treatment (refuse). Relatively large areas estuarine wetlands including mangroves and saltmarsh remain, together with smaller areas of melaleuca and eucalypt vegetation. There is also a lacustrine wetland on the eastern bank. These wetlands filter residential inputs. Mangrove forest lining Hay's Inlet - provided by Unitywater. Water moves very slowly through Hay’s Inlet. Movement is reduced by freshwater inputs and tidal movement (which are often opposing), sand banks that separate fresh and tidal waters, and the shallow, extensive nature of the estuary. The area is prone to flooding. The lower reaches also include part of the Hay’s Inlet conservation parks (1 and 2) and fish habitat area, and the Moreton Bay Ramsar site and Marine Park. The fish habitat area provides for protection of shoal estuarine flats, intertidal fish habitats and stands of the milky mangrove (Excoecaria agallocha), together with limited mosquito control. The area supports a major recreational and small commercial fishery. There is a sewage treatment plant at Redcliffe. The outfall crosses the mudflat to discharge below the tidal zone in Hay’s Inlet. Hornibrook Bridge at the mouth of Hay's Inlet, during removal of old bridge in May 2011 - provided by Unitywater. Main image: Aerial photo of Hay's Inlet in 2010 (centre) with Murrumba Downs in the foreground through to Redcliffe, Moreton Bay and Moreton Island - provided by Unitywater. Walkers, Bells and Humpybong creeksThese subcatchments are flat and underlain by mostly impervious rocks, together with sands and other unconsolidated sediments. There are large areas of alluvium along Hay's Inlet and Bells Creek.Large areas have been cleared for urban residential, together with associated services and recreation, utilities and manufacturing and industry. Humpybong and Bells creeks subcatchments have been completely cleared. Small areas estuarine wetlands including mangroves and saltmarsh remain and other coastal communities including heath remain in the Walkers Creek subcatchment. There are also several lacustrine wetlands across the subcatchments, and seagrass is re-establishing in Deception Bay. Many of the channels are concrete or boulder-lined (including canals) and some channels are piped underground. Water falling on these subcatchments has limited ability to drain and very heavy rainfall can lead to localised flooding. These subcatchment include part of the Moreton Bay Marine Park. Main image: Bells Creek - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. Please note Deception Creek subcatchment is included in the Caboolture Catchment map journal. ConclusionThe Pine Catchment shows how natural and modified features within the landscape impact on how water flows. These issues need to be managed to ensure that the significant natural (and social) values of the catchment are protected, and to minimise impacts on the multitude of values within the catchment and downstream in Moreton Bay, while providing for residential, water supply, farming and other important land uses of the catchment.The South Pine River subcatchment is one of the few remaining subcatchments in South east Queensland that does not have major barrier to water movement. Knowing how the catchment functions is also important for future planning, including climate resilience. With this knowledge, we can make better decisions about how we manage this vital area. Main images: Dayboro rural development and the D'Aguilar Range (top far left); grazing near Dayboro (top right); Strathpine urban development (top far right); aerial photo showing urban residential development, Hay's Inlet and Moreton Bay (bottom centre); Hay's Inlet mangroves (middle right); pineapple farm near Samsonvale (bottom right) - provided by Unitywater. Lake Samsonvale (top middle); Cedar Falls (bottom left) - provided by Moreton Bay Regional Council. AcknowledgementsDeveloped by the Queensland Wetlands Program in the Department of Environment and Science in partnership with: Council of Mayors South East Queensland Department of Natural Resources and Mines This resource should be cited as: Walking the Landscape – Pine Catchment Map Journal v1.0 (2017), presentation, Department of Environment and Science, Queensland. Images provided by: Moreton Bay Regional Council, Unitywater Contact wetlands♲des.qld.gov.au or visit wetlandinfo.des.qld.gov.au DisclaimerThis map journal has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within the document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this education module is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy.Data sources, links and informationSoftware UsedArcGIS for Desktop | ArcGIS Online | Story map journal Some of the information used to put together this map journal can be viewed on the QLD Globe. The Queensland Globe is an interactive online tool that can be opened inside the Google Earth™ application. Queensland Globe allows you to view and explore Queensland spatial data and imagery. You can also download a cadastral SmartMap or purchase and download a current titles search. More information about the layers used can be found here: Source Data Table Flooding Information Moreton Bay Regional Council Other ReferencesCatchment Solution (2016) Greater Brisbane Urban Fish Barrier Prioritisation. [webpage] Accessed 20 September 2016 City of Gold Coast (2021) About water catchments. [webpage] Accessed 25 August 2021 Department of Environment and Science (2013) Aquatic Conservation Assessment Series. [webpage] Accessed 22 September 2016 Healthy Waterways (2016), Pine Catchment 2015 Report Card [webpage] Accessed 20 September 2016 Moreton Bay Regional Council (2015), MBRC Stream Health Monitoring Program–2015. [webpage] Accessed 20 September 2016 Nolte, U. (2011), Stream of High Biodiversity Value in Moreton Bay Region. [webpage] Accessed 20 September 2016 Queensland Government (2016), Key Resource Areas in Queensland. [webpage] Accessed 7 July 2016. Last updated: 25 August 2021 This page should be cited as: Department of Environment, Science and Innovation, Queensland (2021) Pine Catchment Story, WetlandInfo website, accessed 8 May 2025. Available at: https://wetlandinfo.des.qld.gov.au/wetlands/ecology/processes-systems/water/catchment-stories/transcript-pine.html |

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation