|

|

O'Connell Catchment StoryThe catchment stories use real maps that can be interrogated, zoomed in and moved to explore the area in more detail. They take users through multiple maps, images and videos to provide engaging, in-depth information. Quick facts

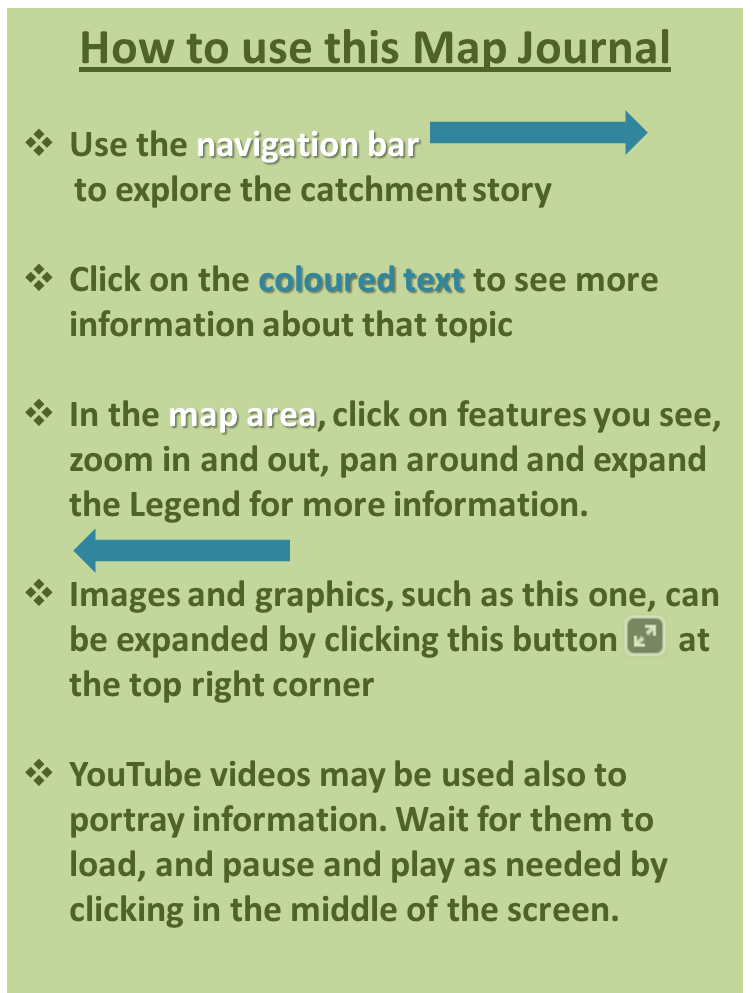

Quick linksTranscriptO'Connell Catchment StoryThis map journal is part of a series prepared for the catchments of Queensland. Understanding how water flows in the catchmentTo effectively manage a catchment it is important to have a collective understanding of how the catchment works. This Map Journal gathers information from experts and other data sources to provide that understanding. The information was gathered using the ‘walking the landscape’ process, where experts systematically worked through a catchment in a facilitated workshop, to incorporate diverse knowledge on the landscape features and processes, both natural and human. It focussed on water flow and the key factors that affect water movement. The Map Journal was prepared by the Queensland Wetlands Program in the Queensland Department of Environment and Science in collaboration with local partners. How to view this map journalThis map journal is best viewed in Chrome or Firefox, not Explorer.

In some slides, due to scale issues, only part of the catchment is shown. Use your mouse to pan around the catchment to view all data. Map journal for the O’Connell Sub-catchment - water movementThis map journal describes the location, extent and values of the O’Connell Sub-catchment*. It demonstrates the key features which influence water flow, including geology, topography, rainfall and runoff, natural features, human modifications and land uses. Knowing how water moves in the landscape is fundamental to sustainably managing the sub-basin and the services it provides. O'Connell Sub-catchment StoryThe O’Connell Sub-catchment is located in north Queensland and is part of the Reef Catchments NRM Region. There are small urban populations at Bloomsbury, Midge Point, Calen, Kuttabul and around Seaforth to Cape Hillsborough. The sub-catchment falls mostly within the Mackay Regional Council boundary but also includes parts of the Whitsunday Regional Council area. The sub-catchment covers approximately 2, 387 square kilometres. There are approximately 1760 kilometres of major stream network, with around 200 km defined as estuarine in the Queensland Wetland Mapping (click for animation). The main waterways are the O'Connell and Andromache Rivers, together with numerous smaller waterways including Waterhole, Alligator, Blackrock, St Helens, Murray, Constant and Reliance Creeks. These all run out into the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. The Proserpine River Sub-catchment is located to the north, the Don Sub-catchment north-west, the Bowen River Sub-catchment is located to the west, and the Pioneer River Sub-catchment is located to the immediate south. Please note there is a drop-down legend for most maps and it can be accessed by clicking on 'LEGEND' at the top right of the map. On this map you can use the drop down legend for the residential, farming and protected areas. Values of the catchmentThe O’Connell Sub-catchment contains many environmental, economic and social values. The sub-basin includes several small townships and the urban and rural residential* areas of Bloomsbury, Midge Point, Calen, Kuttabul and Seaforth with Bucasia and Blacks Beach (Northern Beaches) close to the main township of Mackay (in the Pioneer River Sub-catchment). Most of the sub-catchment is used for grazing on native pastures, together with conservation and natural environments, production forestry, cropping/irrigated cropping (sugar cane) and urban (residential). There are National Parks as well as a number of Conservation Parks and State Forests. The marine environment and coastal waters provide high value areas including around islands and inshore coral reefs. Newry Island is part of a group of hilly islands that form part of the Newry Islands National Park. It is five kilometres off the coast but is not part of the O’Connell Sub-catchment. It is an important feature of this area that it has so many protected areas (15% of the sub-catchment). *Please note the residential areas shown include rural residential as well as other residential area types. Values of the catchment–economicFarming in the sub-catchment includes grazing on native and improved pastures together with irrigated cropping (sugar cane) and production forestry. There is limited mining in the sub-catchment, with only one hardrock Key Resource Area near Farleigh and one further south on the border of the Pioneer. The Sub-catchment estuaries make up three per cent of the extent of estuaries in the Great Barrier Reef catchment (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority 2013) and are important for recreational and commercial fisheries (Lewis et al 2009). There are three Fish Habitat Areas (FHA) – Midge, Repulse and Sand Bay. These FHA’s support commercial, recreational and Indigenous fisheries; barramundi; threadfin salmon, blue salmon; bream; estuary cod; flathead; grey mackerel; grunter; mangrove jack; queenfish; school mackerel; sweetlip; various emperor species; banana and blue-legged king prawns. **Declared Fish Habitat Area summary – Midge, Repulse and Sand Bay (see link at end of map journal for more information). Values of the catchment–environmental and socialThe O’Connell provides important habitat for many marine, estuarine, freshwater and terrestrial species. Many of these species have lifecycles that have connections to the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area. The World Heritage Area includes dugong habitat (protected under extensive dugong protection areas) and there are many coastal and inshore Marine National Park Zones adjacent to this Sub-catchment. The largest protected land area is Eungella National Park, which is predominately in the Bowen River Sub-catchment, but also falls into the O’Connell. Cathu State Forest is also a large protected area in the Sub-catchment. Other areas include Cape Hillsborough National Park and Pioneer Peaks National Park (Mount Blackwood, Mount Jukes and The Leap). There are two listed Threatened Ecological Communities that occur in this sub-catchment. These are the Littoral Rainforest and Coastal Vine Thickets of Eastern Australia (Critically Endangered) and the Broad leaf tea tree (Melaleuca viridiflora) woodlands (Endangered). The wetlands and creeks of the sub-catchment provide habitat for many important aquatic species, including plants, fish and birds. Estuarine areas also support important plants (mangrove, saltmarsh and seagrass), marine turtles, marine mammals and fisheries species. The area around Sand Bay and Repulse FHA contains significant sea turtle nesting areas, including flatback and green turtle nesting area. These areas where there are numerous large and small bays and river mouths provide good habitat for migratory shorebirds. The main shorebird feeding areas appear to be Repulse Bay, St Helen's Bay to Finlayson's Point, Sand Bay to Shoal Point (WetlandInfo, 2017). Protected areas also provide recreational activities such as bush walking, swimming, camping, boating and fishing. These activities not only provide substantial social and health benefits but they are also very important for tourism. Information about the different types of wetlands shown in this mapping is provided here. Natural features–geology and topographyThere are granites to the west with mixed volcanic sedimentary rocks and corresponding complexes of mixed geology; which have a major effect on how water flows in the sub-catchment. The O’Connell River itself as it runs along a fault line. The river may have continued to run to the north historically, whereas now it takes the turn to the east and heads out to the estuary. The dominate geologies are granites and mixed volcanic sedimentary (Carmilla beds) with small areas of alluvium in the main floodplains around the O’Connell and Andromache Rivers, and Blackrock Creek to the south. The majority of the headwaters are in this granite rock type, and in elevated areas provide for fast surface water run-off with little infiltration. The channel shape and floodplain type will have different impacts on sediment generation and erosion. Inset floodplains in the O’Connell catchment provide structure to banks. There are some groundwater dependent ecosystems (fractured rock and alluvial aquifers) along the creek lines in the areas to the north, along the O’Connell and further south at Reedy, One Mile and Blackrock Creeks. The coastal geologies form part of the Campwyn Volcanics and there are areas of the Calen Coal Measures (sedimentary rock) around Revenge, Constant and Reliance Creeks. There is little wetland development along the major watercourses inland – but the coastal sediments and clays silt and sand support low-lying coastal swamps and estuarine wetland development. These different rock types combine to make up the geology of the O’Connell Sub-catchment. Natural features–rainfallThis Sub-catchment receives high to very high rainfall, predominately in the wet season, with the highest rainfall in the peaks in Eungella National Park*. These different rainfall levels combine to make up the rainfall of the O’Connell Sub-catchment. *Rainfall categories: moderate (651-1000 millimetres per year), high (1001-1500 millimetres per year) and very high (1501-2000 millimetres per year Modified features–pre-clearing vegetationVegetation affects how water flows through the sub-catchment, and this process is affected by land use and management practices. Native vegetation slows water, retaining it longer in the landscape and recharging groundwater aquifers, and reducing the erosion potential and the loss of soil from the sub-catchment. Historically, most of the sub-catchment contained eucalyptus woodlands and open forests. There were also large areas of rainforests and scrubs and mangrove and saltmarsh, together with small areas of melaleuca woodlands and other coastal communities and heath. These different vegetation types combined to make up the preclearing vegetation of the O’Connell Sub-catchment.* *Broad Vegetation Groups derived from Regional Ecosystems. Regional Ecosystems are vegetation communities in a bioregion that are consistently associated with a particular combination of geology, landform and soil. Modified features–vegetation and land useNearly half the sub-catchment has been cleared or partially-cleared for a range of rural and urban land uses, particularly grazing on native pastures, production forestry and irrigated /non-irrigated cropping. Eucalyptus-dominated vegetation remains across much of the northern areas and some patches down south in the state forests and national parks, as well as large sections of rainforests and scrub particularly in Cathu State Forest and Eungella National Park. Mangrove forests still line the lower reaches in the coastal low lying swamps. Large areas of vegetation have been cleared in other parts, including eucalyptus-dominated and rainforests and scrubs. Nearly all of the melaleuca open-woodland has been cleared. A range of different management and modification of the natural environment combine to make up the remnant vegetation of the O’Connell Sub-catchment.* *See links at end of this map journal for further details regarding land use classification. Modified features–vegetation clearingEven though a lot of native vegetation has been cleared, there has also been some areas of vegetation that has regrown* since initial clearing. Explore the swipe map using either of the options below.**

These developments and activities change the shape of the landscape and can modify water flow patterns. *Please note this regrowth includes non-native vegetation. **Please note this application takes time to load. Modified features–channels and infrastructureBuildings and important infrastructure such as roads, railways and creek crossings create barriers and impermeable surfaces that redirect water through single points or culverts, leading to channelling of water. This increases the rate of flow and the potential for erosion. The lower reaches around north Mackay have been developed and there are many barriers and impermeable surfaces. There are also numerous smaller cane train tracks across the catchment (not displayed in mapping) due to the sugar production. Modifications to channels, such as straightening and diversions, can also increase flow rates. Infrastructure can also affect fish passage, and several barriers are known to affect fish passage in the O’Connell Sub-catchment. There are a number of fishways to assist with improving fish passage past barriers. A link to the Mackay-Whitsunday Fish Barrier Report can be found at the end of the Map Journal. Modified features–dams and weirs and artificial canalsDams and weirs also modify the natural water flow patterns, by holding water. The sub-catchment has a few rural water storages (farm dams) and artificial canals that capture overland flow. These modify how water flows. These storages can also be filled through pumping from creeks, and this is one of the reasons why there was a water allocation management plan developed for the O’Connell sub-catchment. Modified features–sedimentIncreases in the volume and speed of runoff can increase erosion in the landscape and the stream channels, resulting in sediment being carried downstream and reduced water quality. Works including bank stabilisation and engineered log jams have been implemented to stabilise parts of the O’Connell River Vegetation clearing, particularly in the headwaters of the O'Connell, has caused stream bank and gully erosion resulting in soil running into the O’Connell River. Riparian vegetation plays an important role in minimising the rates of erosion (Alluvium, 2014). A riparian condition index, shows the areas of ‘good, moderate, poor or very poor’ in the major stream systems of the O’Connell Sub-catchment. The system has a very high sediment transport capacity and large volumes of coarse sediment are likely to be mobilised, transported and subsequently deposited further downstream during flood events. The overall stability of channels in a catchment is important in understanding the erosion capability of the system. The stability assessment report categories the main streams in the O’Connell Sub-catchment as ‘stable, minor instabilities, moderate instabilities and major instabilities’. Close proximity to the estuary and coast and as a consequence would have a high delivery of fine material (sediment and attached nutrients) to the coast. Water qualityWater quality is influenced by runoff and point source inputs such as sewage treatment plants, septic tank seepage and stormwater discharge. Most of the sub-catchment uses septic tanks, however there are sewage treatment plants (STPs) at Reliance Creek. Monitoring site information can be found in the gauging station link at the back of the Map Journal. Information on Catchments Loads Monitoring can be found on the Reef Catchments website (see reference section at the back of the Map Journal). Water flowWater flows across the landscape into the O’Connell River and other waterways (click to see animation*). The remaining water either sinks into the ground where it supports a variety of terrestrial and groundwater dependent ecosystems or is used for other purposes. The restricted channels and gullies eventually flatten out to form waterways that meander across the floodplain. They pass through alluvial areas which store and release water, prolonging the time streams flow. *Please note this application takes time to load. The main areasA ‘sub-basin’ or ‘sub-catchment’ is an area with a natural boundary (for example ridges, hills or mountains) where all surface water drains to a common channel to form rivers or creeks.* The O’Connell is listed as a single sub-catchment but consists of several distinct areas which require specific mention:

*Definition sourced from the City of Gold Coast website (see links at the end of this map journal). Andromache River (Mares Nest Creek)The Andromache River flows 46 kilometres from the highlands of the Clarke Connor range before joining the downstream reaches of the O’Connell River (WQIP, 2014). There are ecologically significant waterholes at the confluence of the Andromache and O’Connell Rivers. Eighty percent of the catchment is dominated by grazing with a small amount of land under cane production toward the coastal flats. The remaining 17% of the catchment is National Park and reserve (WQIP, 2014). The majority of the upper headwaters are dominated by granite rock type, moving into alluvium, coastal mud flats, colluvium and soil. The river channel consists of sand, silt, mud and gravel. Relatively small inset floodplains being too small for cropping have remained uncleared and as a result the sub catchment still has reasonable riparian vegetation. Mares Nest Creek is a fast flowing stream, tending to have good base flows all year around. This is a short narrow catchment and has alluvia with groundwater connectivity to underlying fractured rock aquifers. The area between Mares Nest and Andromache confluence there is shallow alluvium. Just after the confluence of Andromache and the O’Connell Rivers there are ecologically significant waterholes which host a mixture of salt and freshwater species. There are waterholes higher up in the catchment, mainly confined by rock bars and sand slugs are a feature through the whole system. Thompson Creek in the Proserpine Basin crosses into the O’Connell Sub-catchment as it can connect with the Andromache during high flow events. Groundwater is not a major source of water supply in this area but a good deep aquifer is found west of Thoopara. O’Connell River (Dingo Creek, Gibson Creek and Boundary Creek)The O’Connell River is one of the largest rivers in the Mackay Whitsunday region (WQIP, 2014). Granites and metamorphics give rise to the sediments which form the alluvium. The O’Connell River itself runs along a fault line. The area has high rainfall and elevation, and there is lots of clearing which has given rise to slumping of the hillsides, stream bank and gully erosion of the sodic soils. Cane and grazing production are the dominant land uses with small urban populations at Bloomsbury and Midge Point (WQIP, 2014). The system has a very high sediment transport capacity and large volumes of coarse sediment are mobilised, transported and subsequently deposited further downstream during flood events. The O’Connell River has been identified as a significant contributor of sediment to the Great Barrier Reef with a large proportion derived from channel erosion (WQIP, 2014). Due to the area being reasonably dry, landholders need to irrigate and are licenced to extract from watercourses. Rural water storages capture some of the overland flow, which can impact the local hydrology. Bloomsbury to Stafford has the most productive groundwater. Above Forbes crossing there is a lot of sand, cobbles, drains and terraces. There is a fishway constructed at Forbes Crossing. Gibson Creek is a perennial system, with slower flow and low transmissivity. There are a lot of sandy areas and shifting creek beds in Dingo Creek. Boundary Creek has a number of waterholes that are significant to this system. This creek has near permanent flow with fractured rock aquifers and little alluvial development. Blackrock Creek (Waterhole Creek and Alligator Creek)In general, the creeks in this area have fast run off, lower elevation, alluvial development. The Waterhole Creek catchment area extends across the coastal lowlands located between the townships of Midge Point to the north and St Helens to the south (WQIP, 2014). Much of this coastal plain has been extensively cleared to support cattle production which extends over almost 80% of the catchment area (WQIP, 2014). Riparian vegetation, mangroves and saltmarshes have been particularly impacted by past land management practices (WQIP, 2014). The Blackrock Creek catchment headwaters originate in the Clarke Range and High Ecological Value forest of Eungulla National Park before entering the coastal plain and estuary at St Helens Bay (WQIP, 2014). Forty seven percent of the lowland are utilised for grazing, while 30% has been developed for cane production that is concentrated on the creek flats (WQIP, 2014). The coastal zone is dominated by grazing to the estuary margins (WQIP, 2014). There are a few headlands at Midge point and Julian Creek with estuarine and mangrove development between these headlands. Sand and fractured rock aquifers are present at Midge Point as well as sodic patches in grazing paddocks. Blackrock Creek has a few small weirs, with a fish way at the culvert on the highway. Upstream has off-stream water holes. Overland water flow is captured in drainage irrigation. Stony, Julian and Hervey creek are heavily grazed with minimal ground cover. Alligator Creek and Blackrock Creek converge upstream of the estuary, due to erosion processes. Alligator Creek moves from a deep and flowing creek to shallow and rocky closer to the coast. Murray Creek (St Helens Creek, Macquarie Creek, Jolimont Creek and Palm Tree Creek)This area has less elevation with four main creeks. St Helens converges with the Murray just upstream of the estuary. Murray Creek flows from headwaters in the Clarke Range east through the coastal plain, entering the Great Barrier Reef lagoon at St Helens Bay and the Newry Island region Dugong Protection Area (WQIP, 2014). Upper areas of the catchment have good quality forest areas, while lowland areas have been developed extensively with almost half of the catchment supporting grazing production and the remaining mainly utilised for cane production (WQIP, 2014). The remaining land use is National Park and wetland with some scattered peri-urban settlements (WQIP, 2014). There are areas of active erosion along Murray Creek. The headwaters are comprised of mixed volcanic and sedimentary rock, siltstone and shale, with alluvium and coastal mud flats further down the system. Murray Creek has near permanent flows and fractured rocks give rise to local groundwater. Waterholes are present on the Murray and some sand slugs, however it retains good connections. Murray Creek is sandy, shallow and wide and it is a slower flowing system. There is reasonable riparian along the system. Macquarie Creek has deep incised channels, and near the highway there is natural cobble and bedrock. Culverts and weirs are also present along Macquarie Creek. Palm Tree Creek has a concrete weir for irrigation which restricts connections. St Helens comes off Mount Dalrymple and is fairly rapid with cobbles. It is a valuable system with a majority of its reach in National Park or Conservation Park and thus has good vegetation and rainforest. St Helens has good riparian upstream, however there are areas where sediment is pushing downstream. Riparian vegetation is poor and patchy close to the mouth. Good waterholes provide habitat for jungle perch and good connections throughout the catchment. Closer to the estuary, flooding can shift the location of the main channel. Constant and Reliance CreekThe geology of the headwaters is sandstone, siltstone, carbonaceous mudstone, coal and conglomerate. These are very short systems, and are estuarine right up into the headwaters. The Constant Creek catchment area drains into the Sand Bay nationally important wetland and Sand Bay Declared Fish Habitat and Dugong Protection Area (WQIP, 2014). The catchment supports diverse land use; grazing, cane, wetland and National Park. Over time, clearing for agricultural production in the catchment has impacted water quality as well as riparian habitat, affecting fish community abundance and diversity (WQIP, 2014). The main land use over time has shifted from cane production to grazing. Constant Creek has near permanent flows and at the mouth there are freshwater wetlands with ponded pastures created from bunds. Acid sulphate soils are present here. The riparian is reasonable all the way through but improves closer to the coast. The main land use is sugar cane. There are few barriers but they reduce connections through the system. The Reliance Creek catchment area is just north of Mackay City sharing a catchment boundary at Shoal Point (WQIP, 2014). Land use is dominated by intensive cane production and grazing (WQIP, 2014). There are some sections where cane is grown through the creek lines. Reliance Creek wetlands and estuary are protected by Reliance Creek National Park. Historically there have been issues with water quality, fish kills and mangrove die-back (WQIP, 2014). Sediment and nutrient trap work has been done on Reliance Creek. The riparian area is reasonable in mid and lower sections of Reliance. There are very gradual sloped banks with some waterholes and reasonable channels, however the flows are not permanent. There are also some areas of cats-claw infestations. This area is unlicensed for groundwater but there is some fractured rock aquifers which are used to supplement irrigation. There are barriers to fish passage and there is one STP on Reliance Creek. ConclusionThe O’Connell Sub-catchment shows how natural and modified features within the landscape impact on how water flows. These issues need to be managed to ensure that the significant natural (and social) values of the sub-basin are protected, and to minimise impacts on the multitude of values within the sub-catchment and downstream in the Great Barrier Reef, while providing for residential, water supply, farming and other important land uses of the sub-catchment. Knowing how the sub-catchment functions is also important for future planning, including climate resilience. With this knowledge, we can make better decisions about how we manage this vital area. AcknowledgementsDeveloped by the Queensland Wetlands Program in the Department of Environment and Science in partnership with:

This resource should be cited as: Walking the Landscape – O’Connell Catchment Story v1.1 (2023), presentation, Department of Environment and Science, Queensland. Images provided by: Reef Catchments, DAF, Catchment Solutions The Queensland Wetlands Program supports projects and activities that result in long-term benefits to the sustainable management, wise use and protection of wetlands in Queensland. The tools developed by the Program help wetlands landholders, managers and decision makers in government and industry. Contact wetlands♲des.qld.gov.au or visit wetlandinfo.des.qld.gov.au DisclaimerThis map journal has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within the document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this education module is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. Data source, links and informationSoftware Used ArcGIS for Desktop | ArcGIS Online | Story Map Journal Some of the information used to put together this Map Journal can be viewed on the QLD Globe. Queensland Globe allows you to view and explore Queensland spatial data and imagery. You can also download a cadastral SmartMap or purchase and download a current titles search. More information about the layers used can be found here: Source Data Table Flooding Information Gauging station information O'Connell River at Staffords Other References Alluvium (2014) O’Connell River Stability Assessment Alluvium (2017). Stream Type Assessment of The Mackay-Whitsundays Region. Report P416018_RO1 by Alluvium Consulting Australia for Reef Catchments. Catchment Solutions (May 2015) Mackay Whitsunday Fish Barrier Prioritisation. Report by Matt Moore Catchment Solutions – Fisheries and Aquatic Ecosystems City of Gold Coast (2021) About water catchments. [webpage] Accessed 25 August 2021 Department of National Parks, Sport and Racing (2016) Declared Fish Habitat Area summary – Midge, Repulse and Sand Bay. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2013) O'Connell basin assessment: Mackay-Whitsunday Natural Resource Management region, GBRMPA, Townsville. Lewis, S.E., Brodie, J.E., Bainbridge, Z.T., Rohde, K.W., Davis, A.M., Masters, B.L., Maughan, M., Devlin, M.J., Mueller, J.F. and Schaffelke, B. (2009) Herbicides: a new threat to the Great Barrier Reef, Environmental Pollution 157(8-9): 2470-2484. Queensland Government (2016) Key Resource Areas in Queensland. [webpage] Accessed 31 October 2016. Reef Catchments (2017) Catchments Loads Monitoring Reef Catchments (2015) O'Connell River Bank Stabilisation project Reef Catchments (2016) Water Quality Improvement Plan – Sub Catchment Map. Last updated: 30 January 2023 This page should be cited as: Department of Environment, Science and Innovation, Queensland (2023) O'Connell Catchment Story, WetlandInfo website, accessed 8 May 2025. Available at: https://wetlandinfo.des.qld.gov.au/wetlands/ecology/processes-systems/water/catchment-stories/transcript-oconnell.html |

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation