|

|

Lower Brisbane Catchment StoryThe catchment stories use real maps that can be interrogated, zoomed in and moved to explore the area in more detail. They take users through multiple maps, images and videos to provide engaging, in-depth information. Quick facts

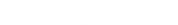

Quick linksTranscriptLower Brisbane Catchment StoryThis map journal is part of a series prepared for the catchments of South East Queensland. Understanding how water flows in the catchmentTo effectively manage a catchment it is important to have a collective understanding of how the catchment works. This map journal gathers information from experts and other data sources to provide that understanding. The information was gathered using the ‘walking the landscape’ process, where experts systematically worked through a catchment in a facilitated workshop, to incorporate diverse knowledge on the landscape features and processes, both natural and human. It focussed on water flow and the key factors that affect water movement. The map journal was prepared by the Queensland Wetlands Program in the Queensland Department of Environment and Science in collaboration with local partners. Main image. Aerial view of the Brisbane River meandering around the city of Brisbane - provided by Brisbane City Council. How to view this map journalThis map journal is best viewed in Chrome or Firefox, not Explorer.

Understanding how water flows in the catchmentThis map journal describes the location, extent and values of the Lower Brisbane Catchment including Oxley, Norman, Bulimba, Enoggera and Breakfast creeks and the associated subcatchments to the north (herein referred to as ‘the catchment’). It demonstrates the key features which influence water flow, including geology, topography, rainfall and runoff, natural features, human modifications and land uses. Knowing how water moves in the landscape is fundamental to sustainably managing the catchment and the services it provides. Lower Brisbane CatchmentThe Lower Brisbane Catchment covers approximately 1,195 square kilometres with approximately 2,475 kilometres of stream network*. The Lower Brisbane River receives water from the Mid Brisbane River, its contributing catchments, and the Bremer River (click to see animation). The Pine Catchment is located to the north, the Logan Catchment is located to the south, the Redlands Catchment is located to the south-east, and the Moreton Bay islands are located to the east. *Based on stream orders 1 to 8 Lower Brisbane Catchment and associated subcatchmentsThe Lower Brisbane Catchment includes the city of Brisbane and falls mostly within the Brisbane City Council boundary but also includes parts of Ipswich City, Logan City and Moreton Bay Regional council areas. The main channel of the Lower Brisbane River is located between two major geological formations: to the north is mostly fractured metamorphic rock and to the south are the more undulating sandstones. There are relatively small areas of alluvium along the main channel, and larger areas of alluvium along other waterways. The catchment includes numerous smaller subcatchments such as Oxley, Norman, Bulimba, Enoggera and Breakfast creeks. It also includes a number of associated subcatchments to the north, such as Kedron Brook and Downfall and Cabbage Tree creeks, which do not flow into the Lower Brisbane River. All waterways flow to Moreton Bay (click for animation). Main image. The city of Brisbane and surrounds - provided by Brisbane City Council. Values of the catchmentThe catchment contains many environmental, economic and social values. The catchment is mostly urban and includes the city of Brisbane. It is the administrative centre of the state government and an important hub for the rest of the state in terms of transport, commercial services, recreation and culture, and manufacturing and industrial.* There are also areas of rural residential and farming such as grazing on native pastures**, horticulture, horse studs and poultry farms. The waterways of the catchment provide for recreational and commercial fisheries. There are conservation and natural areas across the catchment, including protected areas, public nature refuges*** and recreational and cultural areas such as parks and open spaces. There is also reserve land that is in public ownership (managed by local government). The coastal parts include large areas of mangrove and saltmarsh. There has been substantial development over time across coastal areas (click to see interactive swipe map showing changes in coastal development over time - zoom to an area of interest).**** *Please note there is a drop-down legend for most maps and it can be accessed by clicking on 'LEGEND' at the top right of the map. On this map you can use the drop down legend for the land use. **Grazing is mapped as ‘grazing on native pastures’ when there is a substantial native species component, despite extensive active modification or replacement of native vegetation. If there is greater than 50 per cent native pastures then the area is classified as ‘grazing on native pastures’. If there are no native species, the area is classified as ‘grazing on modified pastures (see links at the end of this map journal for further information regarding land use management classification). ***Protected areas of Queensland represent those areas protected for the conservation of natural and cultural values and those areas managed for production of forest resources, including timber and quarry material. The mapped nature refuges are part/s or whole of Lot/s on plan and are gazetted through a voluntary conservation agreement between the state government and private land owner/s. Protected areas and public nature refuges are managed by the state government. ****This application may take time to load. Please note mapping is currently only available for the coastal areas. Main images. Road crossing of Oxley Creek (top left), Forest Lake (top centre), pied oyster catchers (top right), the city of Brisbane (centre), Boondall Wetlands (middle right), CityCat ferry on the Brisbane River (bottom left), Southbank (bottom right) - provided by Brisbane City Council. White Rock (bottom middle) - provided by Ipswich City Council. Boats on lower Norman Creek (middle left) - provided by Norman Creek Catchment Coordinating Committee. Values of the catchment—economicUrban development and associated services (commercial, public, recreation and culture, and Defence) are strong drivers of the local economy. The city is a popular holiday destination, as a River City with a range of outdoor adventures, major attractions and dining options including cruises and ferries, riverside walks, kayaking, the Riverstage, Kangaroo Point Cliffs and Southbank. The city is host to the Brisbane Festival and Riverfire, which is one of Australia’s major international arts festivals and attracts an audience of around one million people every year. Manufacturing, industry and transport are important economic components of the catchment, particularly road corridors, airports, part of the Port of Brisbane and associated shipping channels. There are also small areas of mining and quarrying, including three hard rock Key Resource Areas.* *Please note hard rock extraction shown are within KRA (Key Resource Areas) only. KRAs are identified locations containing important extractive resources of state or regional significance worthy of protection for future use. Some KRAs include existing extractive operations (see link at end of map journal for more information). Main image. Southbank pool and parklands, showing the Brisbane River and city of Brisbane (background) - provided by Brisbane City Council. Values of the catchment—environmental and socialThe catchment contains a number of protected areas, with the largest being D’Aguilar National Park and Boondall Wetlands (part of the Moreton Bay Ramsar site). The catchments also include public nature refuges and conservation and natural areas. The Brisbane River and the freshwater wetlands and creeks of the catchment provide habitat for important species such as birds and platypus. Estuarine areas supports many important species including seagrass, mangroves, saltmarsh, migratory birds, fisheries species (crustaceans and fish), turtles and dolphins. Protected areas also provide recreational activities such as walking, bike riding and bird watching. These activities not only provide substantial social and health benefits but they are also very important for tourism. The Brisbane River and other waterways of the catchment also provide for fishing and kayaking. Information about the different types of wetlands shown in this mapping is provided here. Main image. Recreational use of Kalinga Park - provided by Brisbane City Council. Natural features—geology and topography (northern catchment)Most of the subcatchments north of the Brisbane River are underlain by fractured metamorphic rocks. The fracturing provides for some localised infiltration of groundwater. Many of these areas are also steep, leading to fast runoff of surface waters. The more coastal areas of the northern catchment are underlain by large areas of alluvium and sedimentary rocks, together with basalt and other permeable geologies. There is alluvium along much of the channels, which enables high amounts of water infiltration and recharge of groundwater. This provides an important contribution to springs, creeks, wetlands and terrestrial vegetation year round. Alluvial areas can also be more prone to erosion. Main image. Climbing Kangaroo Point cliffs - provided by Brisbane City Council. Natural features—geology and topography (southern catchment)The subcatchments south of the Brisbane River are underlain by undulating sedimentary rocks, together with alluvium and basalt. These areas enable high amounts of water infiltration and recharge of groundwater, which provides an important contribution to springs, creeks, wetlands and terrestrial vegetation year round. There are also areas of fractured metamorphic and impervious rock across the southern catchment. Runoff from these lower porosity rock areas flows into floodplain alluvium. This groundwater is held up by the underlying impervious rock and supports wetlands and maintains stream flows. The fracturing also provides for some localised infiltration of groundwater. These different rock types combine to make up the geology of the Lower Brisbane Catchment. Main image. White Rock - provided by Ipswich City Council. Natural features—rainfallMost of the catchment experiences high average rainfall (1,001-1,500 millimetres per year), with slightly higher rainfall over Mount Coot-Tha. Parts of the western catchment experience moderate average rainfall (501-1,000 millimetres per year). These different rainfall levels combine to make up the rainfall of the Lower Brisbane Catchment. Natural features—vegetationVegetation affects how water flows through the catchment, and this process is affected by changes in land use. Vegetation assists water to infiltrate into the landscape, reducing surface water flows, retaining water longer in the environment, recharging groundwater aquifers, reducing the erosion potential and issues with water quality and sedimentation further downstream, and also protects banks and shorelines. Wetlands play an important role in soaking up water. Wetlands, including mangrove forests and freshwater systems, release stored water slowly over time, thereby preventing flash flooding and easing droughts. Wetlands also provide habitat for a wide range of important flora and fauna. Estuarine wetlands support seagrass, mangroves, saltmarsh, migratory birds, fisheries species (crustaceans and fish), turtles and dolphins. Freshwater wetlands provide habitat for aquatic plants, frogs, birds and platypus. Historically, most of the catchment contained eucalypt forest, together with rainforest and scrub, melaleuca woodlands, mangrove forest and other coastal communities*. There were also small areas of wet eucalypt forest and low-growing vegetation (tussock grasslands and forblands). These different vegetation types combine to make up the preclearing vegetation of the Lower Brisbane Catchment. Main image. Banks Street Reserve, Breakfast Creek - provided by Brisbane City Council. *Broad Vegetation Groups derived from Regional Ecosystems. Regional Ecosystems are vegetation communities in a bioregion that are consistently associated with a particular combination of geology, landform and soil. Modified features—vegetation clearingOutside the urban footprint, areas of vegetation remain throughout the catchment. This remnant vegetation includes areas of eucalypt forest in the west, and mangrove forests in some tidal and coastal areas. Regrowth** of native vegetation has also occurred since initial clearing in some areas, including the north-west and along upper Oxley Creek. Explore the Swipe Map using either of the options below.* Interactive Swipe App where you can zoom into areas and use the swipe bar (ESRI version) Interactive Swipe App where you can use the swipe bar. Use the white slide bar at the bottom of the map for a comparison (HTML version) These developments and activities change the shape of the landscape and can modify surface and groundwater flow patterns. Main image. Melaleuca tree, Springfield Lakes - provided by Ipswich City Council. *Depending on your internet browser, you may experience issues with one or the other. Please note this application takes time to load. **Smaller areas of regrowth are not shown in this mapping. This dataset was prepared to support certain category C additions to the Regulated Vegetation Management Map under the Vegetation Management (Reinstatement) and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2016. This dataset is described as: The 2013 areas of non-remnant native woody vegetation that have not been cleared between 1988 and 2014 that are homogenous for at least 0.5 hectare and occur in clumps of at least 2 hectares in coastal regions and 5 hectares elsewhere. Modified features—channels and infrastructureModifications to waterways have occurred over time to accommodate increased flow as a result of catchment modification, changes in imperviousness, for infrastructure protection and to reduce localised flooding. Much of the catchment has been urbanised, and there are many impermeable surfaces and artificial waterway features. This increases the rate of flow and the potential for erosion. Buildings and infrastructure such as roads, railways and creek crossings create impermeable surfaces and barriers influencing water and sediment movement, and can also present a barrier to aquatic species. Fishways have been fitted to some barriers, but many remain a barrier to fish migration during low or baseflow conditions, with migration (upstream and downstream) achievable during major flood conditions only. Some barriers restrict passage during medium and/or high flows also. Modifications to channels, including lined channels and bypasses, edge protection and floodplain modifications, often result in increased flow rates and volumes of stormwater moving through waterways. Modified features can also include natural channel design and energy dissipation devices. Channel modifications are common in the Lower Brisbane Catchment. Groundwater interaction occurs with drainage networks across many parts of the catchment, including Norman and Oxley creeks and their tributaries. Sand and gravel extraction can also substantially modify channel beds and flow. There is active erosion (headcuts) moving along several waterways including Woogaroo, Oxley and Sheepstation creeks. Main images. Ridge Street and freeway crossings of Norman Creek (top left) - provided by Norman Creek Catchment Coordinating Committee. Revegetation along Downfall Creek (Raven Street, Chermside West), road crossing of Oxley Creek (top right), energy dissipation baffles in Jindalee Creek (Avondale Rd, Sinnamon Park), edge protection along Kedron Brook (Shand Street, Stafford) - provided by Brisbane City Council. Modified features—dams, weirs and rural water storagesDams and weirs modify the natural water flow patterns, by holding water. This affects how much water flows through the system. There are two dams in the catchment. Enoggera Reservoir is the larger of the two dams and is managed by Seqwater, with the majority of surrounding land managed by Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service. It is mainly used for recreation including mountain biking, walking, swimming and paddle craft. Gold Creek Reservoir is also managed by Seqwater, with the majority of surrounding land managed by Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service. It was originally built to supplement the Enoggera Reservoir, via a tunnel that connected Gold and Enoggera creeks. Mountain biking, walking and horse riding are permitted around this reservoir. Both dams are un-gated (overflow when they reach capacity) and do not include a fishway. The dams present a barrier to fish migration during baseflow conditions, with migration achievable during major flood conditions only. The catchment also has numerous rural water storages and several large water bodies (ponds) associated with historic sand extraction, including along lower Six Mile and mid Oxley creeks. Main images. Enoggera Reservoir showing bank revegetation (top left), Enoggera Reservoir wall (bottom left), Gold Creek (top right, bottom right) - provided by Seqwater. Modified features—sedimentIncreases in the volume and speed of runoff can increase erosion in the landscape and the stream channels, resulting in sediment being carried into the waterways and downstream. Urban runoff has many impacts on waterways, particularly erosion and sedimentation. During any rainfall event, sediment can be transported from natural, disturbed (e.g. construction sites) and impervious urban surfaces, and carried into the stormwater network. Impervious areas and stormwater networks are known to contribute to large stormwater flows with strong erosive power. Stabilisation works have been undertaken across the catchment. Several areas are prone to erosion associated with sodic/erosive soils and development, including Six Mile and Downfall creeks. Recreational access is associated with increased sediment loads on waterways, and is common in natural reserve areas. Main image. Rehabilitation of riparian area - provided by Brisbane City Council. Water qualityWater quality is influenced by runoff and point source inputs. Runoff in this largely urbanised catchment is from a variety of land uses including industrial, commercial and residential areas. Point source inputs include sewage treatment plants, septic tank seepage, stormwater discharge and industrial discharge. There are sewage treatment plants (STPs) at Karana Downs, Goodna, Wacol, Carole Park, Oxley, Fairfield, Gibson Island, Wynnum, Luggage Point and Sandgate. There are also rural areas that use septic tanks, as discussed in the subcatchment slides. Stormwater harvesting projects are being used to provide a sustainable water resource for irrigation of parks and sports fields. This harvesting protects and improves the water quality of stormwater by reducing the discharge of sediments and nutrients into local creeks. During 2016, Healthy Waterways graded the overall Environmental Condition Grade of the Lower Brisbane Catchment as C-.* The overall environmental condition of Lower Brisbane remains fair. Pollutant loads significantly improved from very high to low. Estuarine water quality improved from fair to good due to improved dissolved oxygen in parts of the estuary.** Excerpt from Healthy Waterways report card (larger segment of pie chart indicated better score. See links at end of map journal for more information). *2016 was an unusually dry year. The Environmental Condition Grade improved for many catchments in South East Queensland during 2016 as there was less rainfall and associated run-off carrying sediment and potential contaminants to waterways (rather than an improvement in condition). **Healthy Waterways Lower Brisbane Catchment Report Card (for current report see links at end of map journal). Main image. Recreational use of the Brisbane River and Kangaroo Point cliffs, with the city of Brisbane in the background - provided by Brisbane City Council. Water flow and floodingThe urbanisation of this catchment has substantially modified how water flows across the landscape, particularly across lower lying areas. The hardening up of the catchment reduces water infiltration and increases water runoff and flow, which in turn can contribute to flooding in lower lying areas.* Rainfall is the most important factor in causing a flood, but there are many other contributing factors. When rain falls on a catchment, the amount of rainwater that reaches the waterways depends on the characteristics of the catchment, particularly its size, shape, underlying geology and topography, land use, vegetation, surrounding structures and saturation levels of soil. Main image. Flooded road crossing in the Lower Brisbane Catchment - provided by Brisbane City Council. *This information is presented for broad indicative purposes based on land forms and it does not indicate where flooding may occur. For detailed flooding maps see local council flood mapping and The Brisbane River Catchment Flood Study (links provided at the end of this map journal). Types of floodingFlooding can be associated with one or more sources, including creek, river, overland flow and storm tide. ‘Creek flooding happens when intense rain falls over a creek catchment. Runoff from houses and streets also contributes to creek flooding. The combination of heavy rainfall, runoff and the existing water in the creek causes creek levels to rise. River flooding happens when widespread, prolonged rain falls over the catchment of a river. As the river reaches capacity, excess water flows over its banks causing flooding. River flooding downstream can occur hours after the rain has finished. Overland flow is runoff that travels over the land during heavy rainfall events. Overland flow can be unpredictable because it is affected by localised rainfall and urban features such as stormwater pipes, roads, fences, walls and other structures. The actual depth and impact of overland flow varies depending on local conditions but it generally occurs quickly. Storm tide flooding happens when a storm surge creates higher than normal sea levels. A storm surge is caused when a low pressure system or strong onshore winds force sea levels to rise above normal levels. The impact from storm tide or storm surge is increased during high tides and king tides and can affect low-lying areas close to tidal waterways and foreshores. Floodwater may rise very slowly and be slow moving. This is normally associated with Brisbane River flooding, which occurs after prolonged periods of heavy rain across the whole catchment. Floodwater can also rise quickly and be very fast moving, and then recede quickly. This is normally associated with creek flooding.’* *Brisbane City Council (2016), Flooding in Brisbane - A guide for residents (see links at the end of this map journal). Water flowWater flows across the landscape into streams/channels and eventually into the Lower Brisbane River or directly into Moreton Bay (click to see animation*). The remaining water either sinks into the ground, where it supports a variety of terrestrial and groundwater dependent ecosystems, contributes to overland flow, or is used for other purposes. Flow (top) and flooding (bottom) of Norman Creek at Arnwood Place, Annerley - provided by Norman Creek Catchment Coordinating Committee. *Please note this application takes time to load. The subcatchmentsA catchment is an area with a natural boundary (for example ridges, hills or mountains) where all surface water drains to a common channel to form rivers or creeks.* Larger catchments are made up of smaller areas, sometimes called subcatchments. The Lower Brisbane Catchment consists of large and small subcatchments. Most of these subcatchments flow into the Brisbane River, however some flow directly into Moreton Bay. The characteristics of each subcatchment are different, and therefore water will flow differently in each one. On the following slides the subcatchments have been grouped based on geology, land use and flow characteristics. *Definition sourced from the City of Gold Coast website (see links at the end of this map journal). Six Mile to Wolston creeksThe headwaters of these subcatchments are steep to undulating and receive moderate to high rainfall over mostly fractured sedimentary and impervious rock. Surface water runoff is high, creek flow is fast and the system can be influenced by riverine flooding. Most lower reaches are tidal. Areas of fractured sedimentary rocks and alluvium provide for local groundwater recharge. There are springs along upper Six Mile Creek. Hard urban surfaces have reduced infiltration and increased flow along many waterways. Much of these subcatchments have been cleared for urban and rural residential, associated services, manufacturing and industrial, grazing on native pastures, and mining and quarrying. Large eucalypt forests remain in the conservation areas, together with some rainforest and scrub, and other coastal communities. There has been some regrowth since initial clearing. Many channels are highly modified. Historic extraction has created water bodies (Swanbank) and areas of active erosion (headcuts) (Six Mile Creek). Some erosive/sodic soils have been exposed by development. A wide range of stormwater quality devices have been installed, including constructed wetlands (Springfield Lakes development). There are large areas of wetland, including perched wetlands along upper Sandy Creek. Pooh Corner has near-permanent flow and supports native fish communities. Main images. Melaleuca tree at Springfield Lakes (top left), rocky substrate at Springfield Central (top middle), Ipswich's floral emblem Plunket malee at White Rock (top middle), Six Mile Creek at Redbank Plains (top right), Springfield Lakes (bottom right) - provided by Ipswich City Council. Wolston Creek (bottom left) - provided by Brisbane City Council. Oxley Creek and tributariesUpper Oxley Creek is steep to undulating and receives high rainfall over a mostly impervious geology. Surface water runoff is high and creek flow is fast. Areas of fractured sedimentary rock and alluvium provide for local groundwater recharge, and there is also an aquifer recharge area. There are several spring-fed area in the mid subcatchment (Sheepstation Gully and Sunnybank). The system can be influenced by riverine flooding. Much of these subcatchments have been cleared for urban and rural residential, associated services, grazing on native pastures, Defence, manufacturing and industrial, mining and quarrying, waste treatment, horticulture and intensive animal husbandry. Large eucalypt forests remain, mostly within conservation areas and on Defence land, together with other coastal communities and mangrove forest. There has been some regrowth since initial clearing. Oxley Creek floods due to several systems converging, the large upstream catchment, the relatively high groundwater table in the alluvial deposits, and the relatively flat, low-lying landscape. Forest Lake is a residential development around an artificial lake, which is managed as a regulated dam and includes swales, check dams and a variety of other water sensitive designs. There are large areas of wetland, including Archerfield wetlands, and many rural water storages across the mid and upper parts. There is some tidal influence to Archerfield. Main images. Reaches of upper and mid Oxley Creek (top images), Forest Lake (bottom left), road crossing of Oxley Creek (bottom right), - provided by Brisbane City Council. Norman Creek and tributariesThese subcatchments are flat and receive high rainfall over mostly fractured metamorphic rocks. Most surfaces have been hardened-up by development, although there are several large parks. Many channels have been heavily modified and many are piped underground and channelised. Surface water runoff is high, creek flow is fast and there is flooding associated with overland flow and the hard, flat landscape. The lower parts of the system can be influenced by riverine flooding. There are estuarine wetlands along the lower reaches, and a constructed freshwater wetland on Bridgewater Creek (Bowie’s Flat Wetland). Wetlands (mangroves) slow water flow and can result in localised flooding, however these systems are essential for other services. Areas of fractured rock and alluvium provide for local groundwater recharge, and there is groundwater interaction with stormwater networks. Ekibin, Sandy and Bridgewater creeks are spring-fed and near-permanent. Mott Creek is spring-fed and permanent. Most of the subcatchments have been cleared for urban residential and associated services, together with manufacturing and industrial. Areas of eucalypt and mangrove forest remain. There has been almost no regrowth since initial clearing, however some areas along the waterways have been revegetated by the Norman Creek Catchment Coordinating Committee and council. The tidal interface is at Hanlon Park. Historically the interface was upstream from this location but it is now restricted by the weir, which overtop in mid to large flows. The weir impedes fish passage during low to mid flow. Main images. Norman Creek at Arnwood Place (top left), Norman Creek at Greenslopes Demonstration Project (top middle), Ridge Street and freeway crossings of Norman Creek (top right), estuarine reaches of Norman Creek at Heath Park (bottom left), Glindemann Creek at Glindemann Park (bottom right) - provided by Norman Creek Catchment Coordinating Committee. Bulimba Creek and tributariesThese subcatchments are undulating to flat and receive high rainfall over mostly fractured metamorphic and impervious rocks. Surface water runoff is high, however creek flow tends to be slow due to the flat landscape, areas of wetland, porous geologies and the building up of lower-lying land. The system can also be influenced by riverine flooding. The porous areas provide for groundwater recharge and there are several springs (Bulimba East and Spring creeks). The Bulimba East Creek aquifer was used by market gardens. Rural water storages and weirs are currently being used for irrigation. Most of these subcatchments have been cleared for urban and rural residential, associated services, manufacturing and industrial, mining and quarrying, intensive animal husbandry and horticulture. Areas of mangrove and eucalypt forest remain, and large areas have regrown since initial clearing. The headwaters include part of Toohey Forest Conservation Park. The lower reaches are mostly modified, and pick-up sediment from urban areas and sediments loads are moving down the catchment. Toohey Forest Conservation Park - provided by Brisbane City Council. There are large areas of wetland, including the oxbow near the Port of Brisbane. There are also artificial wetlands along mid Bulimba Creek. Bulimba Creek is tidal to between Meadowlands and Old Cleveland roads. Hemmant Quarry Reserve - provided by Brisbane City Council. Kholo to Pullen Pullen creeksThe headwaters of most of these subcatchments are steep and receive moderate to high rainfall over fractured metamorphic and impervious rocks. Surface water runoff is high and creek flow is fast. Areas of sedimentary rock and alluvium provide for local groundwater recharge. Lower lying areas have been cleared for rural residential, grazing on native pastures and waste treatment, together with urban residential, services and other farming. Large eucalypt forests remain, mostly in the upper parts, together with rainforest and scrub. Most of the cleared vegetation has regrown since initial clearing. This is a high biodiversity area with good fish habitat and native communities, across most of these small catchments. Septic systems are used across large areas of these subcatchments. Moggill Creek and tributariesThe headwaters of these subcatchments are steep and receive high rainfall over fractured metamorphic rocks. Surface water runoff is high and creek flow is fast. Gold Creek flows through Brisbane Forest Park. Upper Gap Creek is one of the most ephemeral systems in the Lower Brisbane Catchment. Alluvium along the channel and fractured rock provide for local groundwater recharge. There are a few isolated springs (upper Moggill and Gold creeks). Much of these subcatchments have been cleared for urban and rural residential, together with associated services, horticulture and intensive animal husbandry. Large eucalypt forests remain, mostly in the conservation areas, together with rainforest and scrub. Most of the cleared vegetation has regrown since initial clearing. There are many rural water storages. Gold Creek Dam is un-gated and surrounded by Brisbane Forest Park. Moggill Creek supports one of the most diverse aquatic communities (plants and fish) in the Brisbane area. There is tidal influence from the Brisbane River upstream to Moggill Road. Some roads are known to be affected by localised flooding and sedimentation. Some erosion and sedimentation along Gap Creek is associated with recreational use of the slopes, with a lot of gravel upstream and fine sediments further downstream. Main image. Gold Creek dam wall - provided by Seqwater. Cubberla to Toowong creeksThe headwaters of these catchments are steep (Mount Coot-Tha) and receive high rainfall over fractured metamorphic rocks. Surface water runoff is high, creek flow is fast and the system can be influenced by riverine flooding (lower Witton and Toowong creeks). Perrin Park acts as a detention basin and also accumulates flood debris. Some channels have been modified to increase flow (lower Witton and Toowong creeks). Alluvium along the channel and fractured rock provide for local groundwater recharge and there are some springs (upper Toowong Creek). Most of these subcatchments have been cleared for urban and rural residential, and associated services. Eucalypt forest remains in some parts (mostly Mount Mount Coot-Tha Forest), however there has been very little regrowth since initial clearing. There is erosion and sedimentation along Cubberla Creek associated with recreational use of the slopes, and along Toowong Creek. Witton, Sandy and Toowong creeks have a tidal influence. There is a waterfall where Witton Creek enters the Brisbane River. There are large storages associated with the golf courses and Mount Coot-Tha Botanical Gardens, and a small pond in Anzac Park. Enoggera and Breakfast creeks and tributariesThe headwaters of these subcatchments are steep, flow through conservation areas and Defence land (including adjacent services) and receive high rainfall over fractured metamorphic rock. Surface water runoff is high and creek flow is fast. The lower parts are prone to flooding, and there are many channel modifications and stormwater devices. Alluvium along the channel and fractured rock provide for local groundwater recharge. There are some isolated springs. The lower parts have been largely cleared for urban and rural residential, together with associated services and manufacturing and industrial. Large eucalypt forests remain in the upper parts, together with wet eucalypt forest and rainforest and scrub, and some of the cleared vegetation has regrown since initial clearing. Enoggera Reservoir is surrounded by Brisbane Forest Park and used for recreation. There is some erosion and sedimentation downstream of recreational trails. Fish Creek supports native fish communities throughout the year. There are many road crossings, weirs and other barriers, some of which are fitted with fishways (Bennett Road). Bancroft Weir (upstream of Kelvin Grove Road) limits the tidal extent and restricts movement of diadromous fish. Ornate rainbowfish won’t cross saline water and are isolated in tributaries upstream of the weir. Banks Street Reserve on Breakfast Creek, Alderley - provided by Brisbane City Council. Main image. Enoggera Reservoir dam wall - provided by Seqwater. Upper main channel and adjacent subcatchmentsThe upper main channel (upstream of Bulimba Creek) is semi-confined in some parts, and confined in others, between primarily metamorphic rock to the north and sedimentary rock to the south. It is tidal to the Mid Brisbane. The channel is deep and permanently flowing. The area is mostly flat and underlain by hard geologies, with alluvium along parts of along the channel. Areas of alluvium and fractured rock provide for local groundwater recharge. This area has been largely cleared for urban and rural residential, associated services, manufacturing and industrial, farming and other minor land uses. Small areas of eucalypt forest, rainforest and scrub, and mangrove forest remain, and there has been some regrowth since initial clearing. Some areas are prone to flooding and tributaries can be influenced by flooding of the main river channel. The multiple catchments and stormwater entering the channel has increased flow rates and paths. Multiple structures along and across the waterway can affect flow, together with bank modification (e.g. concrete revetments and rock lining), however there are no major barriers. There are also several instream rock bars. Main images. CityCat ferry on the Brisbane River with the city of Brisbane in the background (top left), Southbank (top right), the city of Brisbane at night (bottom left), Anstead Bushland Reserve on the banks of the Brisbane River (bottom right) - provided by Brisbane City Council. Moggill ferry (top middle) - provided by Ipswich City Council. Lower main channel and adjacent subcatchmentsThe lower main channel (downstream of Bulimba Creek) is largely semi-confined, deep (sediment removal) and permanently flowing (strongly tidal). Most of the area is flat and underlain by unconsolidated materials. This area has been largely cleared for manufacturing and industrial, part of the Port of Brisbane and Brisbane airport, waste treatment and disposal (sewage), urban and rural residential and other minor land uses. Mangrove forest remains on low-lying land, and there has been some regrowth since initial clearing. Much of the river bank has been hardened-up by development. Extensive areas have been reclaimed and are no longer part of the aquatic system, including Port of Brisbane and Brisbane airport. Many areas have also been built-up by development (industrial areas of Boggy Creek subcatchment), which alters water flow rates and paths. Railway and road crossing culverts also alter water flow and sedimentation. There are multiple structures along and across the waterway but no major barriers. There is extensive bank modification, such as concrete revetments, pylons and rock lining, particularly at the Port of Brisbane. The lower parts are prone to flooding. Flood protection works and channel modifications have occurred in the area over time. Sediment and vegetation management works are completed by Council in the area. The Moreton Bay Ramsar site also includes parts of this area. A shorebird high tide roosting area has been created at the Port of Brisbane. It is used by a large variety of species including sandpipers, plovers, godwits, curlews, terns, ducks, pelicans and egrets. Cabbage Tree Creek and tributariesThese catchments are undulating to flat and receive moderate to high rainfall. The upper parts are underlain by mostly fractured metamorphic rock with alluvium in the channels. Surface water runoff is high and creek flow is fast, however the alluvium and fracturing provide for local groundwater recharge. The lower parts are underlain by mostly porous geologies and include an aquifer recharge area. These areas would have provided for groundwater recharge, but have been mostly hardened-up by development. Nearly all of these subcatchments have been cleared for urban and rural residential and associated services, together with manufacturing and industrial, waste treatment and disposal and intensive animal husbandry. Areas of eucalypt forest, melaleuca woodland and mangrove forest remain (parts of Deagon and Boondall wetlands), however there has been very little regrowth since initial clearing. The lower parts are prone to flooding. Flow is increased by channel modification (including sediment removal) and vegetation removal by council. There are many road crossings, weirs and other barriers to flow. Stream rehabilitation work is being undertaken to improve fish passage (Bangalow Street trial). There is waterway enhancement by council, to re-naturalise the waterway. There are highly dispersive soils along parts of Little Cabbage Tree Creek. Lemke Road is the limit of tidal extent. Main image. View across Cabbage Tree Creek to Shorncliffe, from the Boondall Wetlands bird hide - provided by Brisbane City Council. Downfall and Nundah creeks and tributariesThese subcatchments are mostly flat and receive high rainfall. The upper parts are underlain by mostly hard rock, with alluvium along the channel. Surface water runoff is high and creek flow is fast, however the alluvium and fracturing provide for local groundwater recharge. The lower parts are underlain by mostly porous geologies and include aquifer recharge areas. This would have provided for groundwater recharge but large areas have been hardened-up by development. Nearly all of these subcatchments have been cleared for urban and rural residential and associated services, together with manufacturing and industrial, horticulture and intensive animal husbandry. Small areas of mangrove forest, eucalypt forest, melaleuca woodland and other coastal communities remain (Boondall Wetlands), and there has been some regrowth since initial clearing. The lower parts are prone to flooding. Flow is increased by channel modification, and wetlands have been constructed to receive stormwater. A weir downstream of Groth Road forms a small detention basin. There are highly dispersive soils along parts of Somerset and Downfall creeks (dog off-leash area at Brickyard Road). Erosion along Downfall Creek is changing the stream structure, such as Seventh Brigade Park. There is sedimentation in some areas, such as behind Chermside Shopping Centre at Kittyhawk Road and Zillman Waterholes. The Moreton Bay Ramsar site includes parts of these subcatchments. Kedron Brook and tributariesThe headwaters of these subcatchments are steep and receive high rainfall over mostly fractured metamorphic rock with alluvium in the channels. Surface water runoff is high and creek flow is fast, however the alluvium and fracturing provide for local groundwater recharge. The lower parts are underlain by mostly porous geologies and include an aquifer recharge area. This would have provided for groundwater recharge but large areas have been hardened-up by development. Most of these subcatchments have been cleared for urban and rural residential and associated services, together with part of the Brisbane Airport, plantation forestry, manufacturing and industrial, grazing on native pastures, mining and quarrying and horticulture. Areas of eucalypt forest, melaleuca woodland, mangrove forest and other coastal communities remain, and there has been some regrowth since initial clearing. The lower parts are prone to flooding. Flood protection works and channel modifications have occurred in the area over time. Sediment and vegetation management works are completed by Council in the area. The headwaters of Cedar Creek flow through D’Aguilar National Park and have a steep, rocky channel. As the landscape flattens out, fine sediments are deposited and there is a silty delta along lower Cedar Creek. There are several weirs (Levitt Rd and Schultz Canal) and stormwater detention basins across these subcatchments. There is tidal influence along Kedron Brook to Shaw Park. Bramble BayBramble Bay* was the most degraded embayment of Moreton Bay during 2016, primarily due to nutrient and sediment inputs from the Brisbane and Pine rivers. Nitrogen has been decreasing since the upgrade of the Luggage Point Sewage Treatment Plant (STP) in 2001, however poor flushing continues to reduce water quality.** Historically, dugongs and turtles grazed on seagrass beds within Bramble Bay, but high turbidity and nutrients eliminated these beds at least 30 years ago and current conditions are unsuitable for re-establishment.** *Bramble Bay extends from the mouth of the Brisbane River north to Woody Point at the Redcliffe Peninsula. Yellow dashed line indicates approximate location. **Healthy Waterways report card (see links at the end of this map journal). ConclusionThe Lower Brisbane Catchment shows how natural and modified features within the landscape impact on how water flows. These issues need to be managed to ensure that the significant natural (and social) values of the catchment are protected, and to minimise impacts on the multitude of values within the catchment including Moreton Bay, while providing for residential, commercial and other important land uses of the catchment. Knowing how the catchment functions is also important for future planning, including climate resilience. With this knowledge, we can make better decisions about how we manage this vital area. Main mages. Boondall Wetlands (top left), rural development along Wolston Creek (top right), road crossing of Oxley Creek (middle left), Forest lake residential development (bottom left), CityCat ferry on the Brisbane River (bottom centre), Southbank (bottom right) - provided by Brisbane City Council. Urban parklands at Norman Park (top middle) - provided by Norman Park Catchment Coordinating Committee. AcknowledgementsDeveloped by the Queensland Wetlands Program in the Department of Environment and Science in partnership with: Brisbane City Council Ipswich City Council Logan City Council Council of Mayors South East Queensland Queensland Urban Utilities Healthy Land & Water Seqwater Norman Creek Catchment Coordinating Committee Bulimba Creek Catchment Coordinating Committee Oxley Creek Catchment Association Kedron Brook Catchment Network Cabbage Tree Creek Catchment Committee Inc. Save Our Waterways Now (SOWN) This resource should be cited as: Walking the Landscape – Lower Brisbane Catchment map journal v1.0 (2017), presentation, Department of Environment and Science, Queensland. Images provided by: Brisbane City Council, Ipswich City Council, Norman Creek Catchment Coordinating Committee The Queensland Wetlands Program supports projects and activities that result in long-term benefits to the sustainable management, wise use and protection of wetlands in Queensland. The tools developed by the Program help wetlands landholders, managers and decision makers in government and industry. Contact wetlands♲des.qld.gov.au or visit wetlandinfo.des.qld.gov.au Disclaimer This map journal has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within the document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this education module is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. Data source, links and informationArcGIS for Desktop | ArcGIS Online | Story Map Journal Some of the information used to put together this map journal can be viewed on the Queensland Globe. The Queensland Globe is an interactive online tool that can be opened inside the Google Earth™ application. Queensland Globe allows you to view and explore Queensland spatial data and imagery. You can also download a cadastral SmartMap or purchase and download a current titles search. More information about the layers used can be found here: Source Data Table Flooding Information Brisbane City Council Ipswich City Council Logan City Council Moreton Bay Regional Council Other References BOM (2016), Climate Data Online. [webpage] Accessed 5 December 2016. Brisbane City Council (2016), Flooding in Brisbane - A guide for residents. [webpage] Accessed 21 February 2017. City of Gold Coast (2021) About water catchments. [webpage] Accessed 25 August 2021 Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (2010), Australian Land Use Management Classification. [webpage] Accessed 5 December 2016. Healthy Waterways (2016), Lower Brisbane 2016 Report Card. [webpage] Accessed 5 December 2016. Healthy Waterways (2016), Western Bays 2016 Report Card. [webpage] Accessed 5 December 2016. Queensland Government (2017), Brisbane River Catchment Flood Study. [webpage] Accessed 31 May 2017. Queensland Government (2016), Key Resource Areas in Queensland. [webpage] Accessed 5 December 2016. Last updated: 25 August 2021 This page should be cited as: Department of Environment, Science and Innovation, Queensland (2021) Lower Brisbane Catchment Story, WetlandInfo website, accessed 8 May 2025. Available at: https://wetlandinfo.des.qld.gov.au/wetlands/ecology/processes-systems/water/catchment-stories/transcript-lower-brisbane.html |

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation