|

|

Treatment wetlandsTreatment wetlands — Construction and operationSelect from the tabs below ApprovalsApprovals may apply to the construction of a treatment system. Contact your local government before any construction is undertaken to understand requirements. For example:

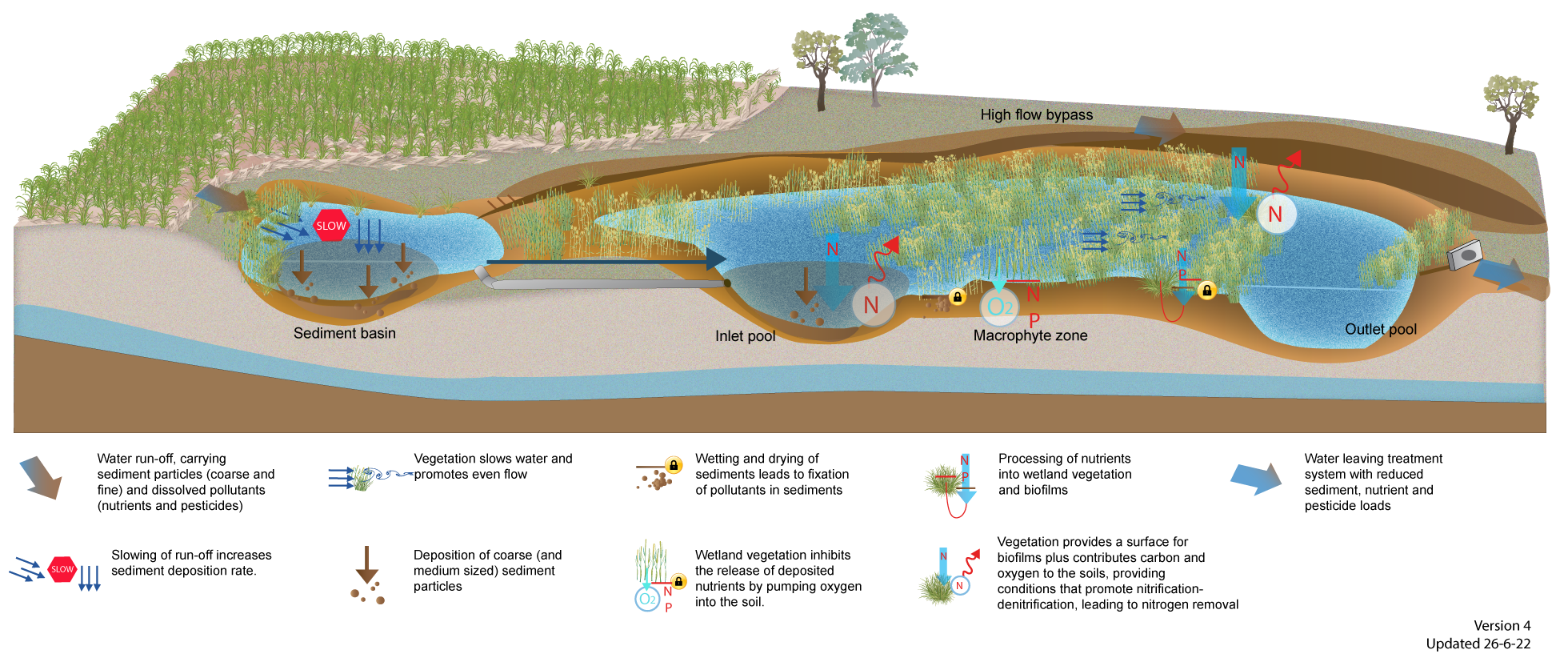

It is also recommended that local Traditional Owners are engaged to ensure no sites or items of cultural significance are disturbed during excavation. Engineering advice should be sought prior to construction to ensure the treatment system is sized and sited appropriately, considering soil suitability, groundwater and local hydrology. Public health and safety should also be considered. ConstructionTreatment wetlands often require considerable and potentially detailed earthworks to create the required bathymetry for the sediment basin and treatment wetland. An engineer with experience in treatment wetlands should be engaged to provide technical advice on the earthworks required to achieve the specific design requirements. Inlet and outlet structures will need to be installed and the levels checked to ensure the hydrology of the treatment wetland functions as designed.

Earthworks should occur during the dry season to minimise the risk of sediment loss. Drainage should bypass the construction site until construction is complete and then be controlled to minimise erosion of the bare soil. Some wetlands may need a compacted clay base to prevent losses to groundwater. Topsoil should be stripped, stockpiled, and replaced as a growing media in the macrophyte zone. EstablishmentTreatment wetlands require large numbers of new plants, primarily reeds and sedges for the macrophyte zone. These can be costly and must be budgeted upfront as dense macrophytes are critical to the effective treatment of water. Plants should be sourced as early as possible at the start of the project to ensure availability (preferably with local provenance). Local guidelines for plant selections should be used where available. Wetland plant guides are available for the Wet Tropics, Burdekin and Mackay Whitsundays regions (See Plant Guides). Natural vegetated systems such as waterways, wetlands and riparian zones can be used as a regional reference from which to create a list of suitable species. Alternatively, locally occurring species can be encouraged to establish in the new treatment wetland, particularly if earthworks were not extensive and vegetation was retained on site (i.e. wetland was created through hydrological modifications). If seed can be obtained, it may be more cost-effective to establish vegetation via seeding. Before planting soil testing should be completed to ensure suitability for plant growth. Vegetation should ideally be planted in bands of the same species running across/perpendicular to the water flow to promote uniform water flow through the macrophyte zone (Figure 10).

Planting should be timed to allow for adequate establishment/root growth before the wet season. Planting early in the year (April– May) means you can take advantage of available soil moisture. Some irrigation may be required to help with establishment. Some treatment wetland trials in Queensland have had poor macrophyte establishment, due to water birds pulling out seedlings and/or the young plants being drowned out due to inability to regulate water levels during the early stages of the wetland. The most important preventative measure for managing bird impact, is to achieve rapid vegetation cover so that any bird damage is offset by new vegetation growth. Direct seeding of a cover crop through the macrophyte zone is an effective way to limit predation. Suitable cover crop species include Juncus spp, Cyperus spp, Philydrum lanuginosum and sterile pasture grasses (rye, millet). Water levels may need to be managed during plant establishment. As a general guide, the water depth should not exceed half the average plant height for more than 20% of the time (Figure 7)[5]. The water levels can be controlled by closing the inlet and bypassing additional flows around the wetland or draining the wetland via the outlet (depending on the design). Comprehensive guidance on the establishment and management of vegetated stormwater systems, including wetlands, is provided in the guideline, “Construction and Establishment Guidelines: Swales, Bioretention Systems and Wetlands, Version 1.1, April 2010[4]. It will take between two months to one year for a treatment wetland to reach efficient and relatively consistent nitrogen removal performance[3][1]. This will depend on plant establishment. OperationOnce established there are minimal requirements for operating the wetland beyond potentially adjusting the wetland outlet to limit inundation periods during the wet season and retaining water during the dry season. MaintenanceMaintaining healthy vegetation and even water flow in a treatment wetland are the key maintenance objectives.

MonitoringOnce established, treatment wetlands should be inspected every six months or after every major rain event to identify:

Monitoring the treatment effectiveness of treatment wetlands is recommended to assess if the wetland is performing as designed. Monitoring requires collecting water samples at the inlet/s and outlet/s of the wetland. This includes any groundwater infiltration or exfiltration. This will estimate the percentage sediment or nutrient reduction. It is essential to also monitor water flow at the site at the time of sampling to calculate load reduction. Further guidance on designing a monitoring program for assessing nitrogen removal by treatment wetlands and vegetated drains is provided in Monitoring Guidelines to quantify nitrogen removal in vegetated water treatment systems. Lifespan/replacementSediment and organic matter may accumulate in the treatment wetland over time reducing the depth and creating uneven bathymetry. Similarly, soils in treatment wetlands can become 'saturated' with phosphorous, so that their effectiveness in removing phosphorous diminishes with time[1]. With correct wetland design, construction and maintenance, together with farm best management practice, an effective life of at least 30-50 years can be assumed[2]. This will also minimise costly earthworks, with significant clean-out limited to the sediment basin. DisclaimerIn addition to the standard disclaimer located at the bottom of the page, please note the content presented is based on published knowledge of treatment systems. Many of the treatment systems described have not been trialled in different regions or land uses in Queensland. The information will be updated as new trials are conducted and monitored. If you have any additional information on treatment systems or suggestions for additional technologies please contact us using the feedback link at the bottom of this page. References

Last updated: 11 March 2024 This page should be cited as: Department of Environment, Science and Innovation, Queensland (2024) Treatment wetlands — Construction and operation, WetlandInfo website, accessed 8 May 2025. Available at: https://wetlandinfo.des.qld.gov.au/wetlands/management/treatment-systems/for-agriculture/treatment-sys-nav-page/constructed-wetlands/construction-operation.html |

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation