|

|

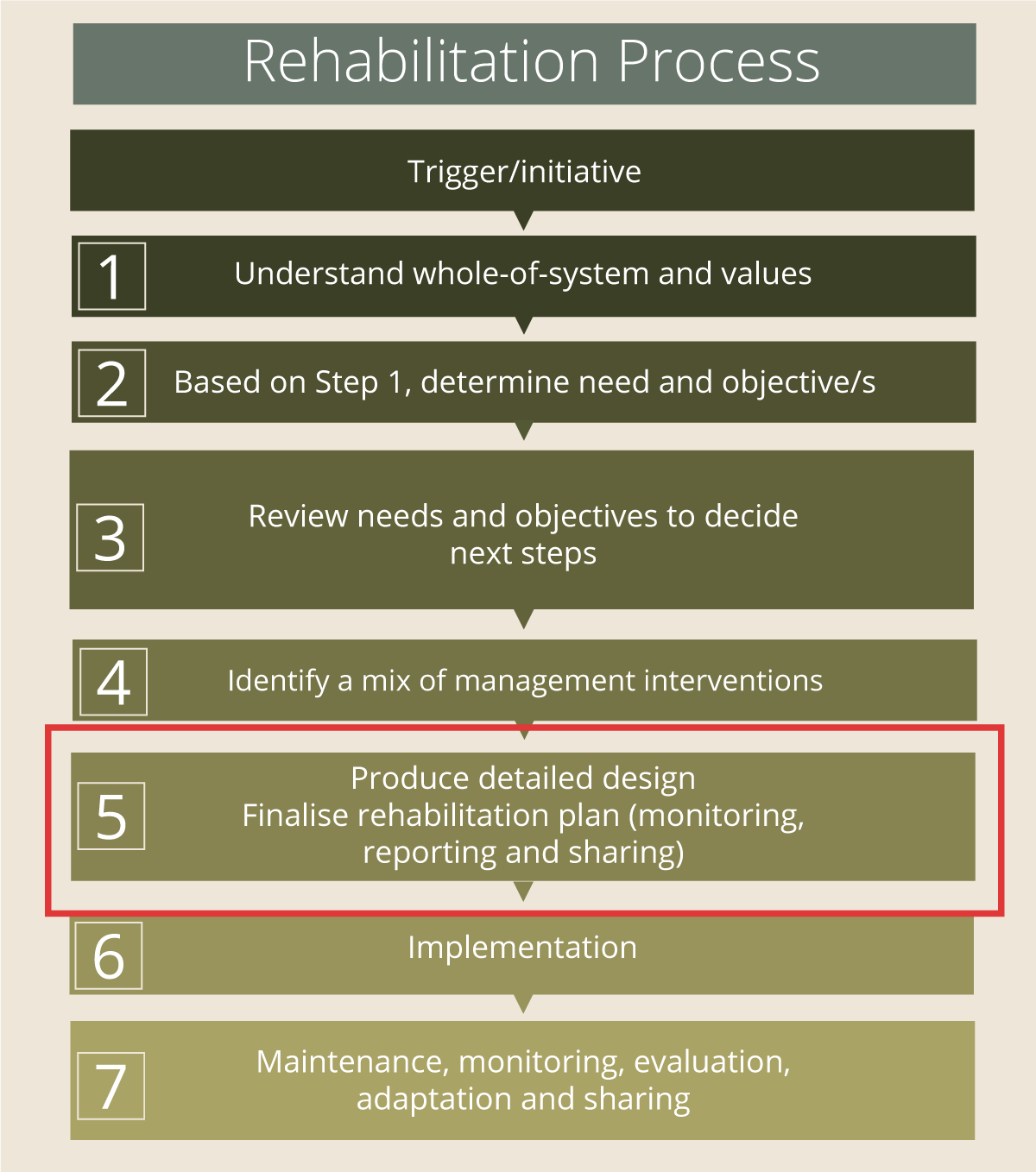

Step 5: Produce detailed designOnce the mix of management interventions that address the objectives have been identified it is necessary to develop, document and cost a detailed design plan. Designs are needed for all management interventions, not just engineered solutions. Maintenance, monitoring and engagement activities for the life of the project also need to be designed. Legal and safety requirements as well as timelines for approvals need to be considered. The detailed design needs to be guided by suitably qualified experts (e.g. a fluvial geomorphologist can design the work but it may need to be signed off by a registered engineer), and include local knowledge and input. Once finalised, a review of the design plan (including ground-truthing), will assist with determining the feasibility of the proposed management interventions (i.e. can it be implemented at the intended locations, at the appropriate scale, in the sequence necessary and within the available budget?). Designing for a mix of interventionsDepending on the mix of management interventions selected to achieve the objective, the design may need to incorporate more than one site and/or more than one intervention. In simple cases there may be a single site requiring rehabilitation and a clear intervention. Often rehabilitation designs are restricted to a single landholder’s property or a reach that is a few kilometres in length. In complex cases, multiple sites may need to be rehabilitated to produce the desired outcomes. In these situations, the design must consider all the sites and the range of interventions required. Examples include:

Approvals and legal obligationsEnsure that the actions do not cause environmental harm or break the law. Federal, State and local legislation and policy and planning need to be considered in any rehabilitation and management. These approvals can be lengthy and expensive and need to be factored in early in the design process. They may include approvals for planning, species permits, earth works, sediment and erosion control. Relevant occupational health and safety policies and requirements need to be observed. Staging of interventionsStaging of management interventions needs to be considered in the detailed design for both simple and complex rehabilitation projects. For example, if active revegetation is the intervention option selected, a stock exclusion fence may need to be constructed before vegetation is planted. Designing for soil requirements, ground cover and earthworks

Designing for plant selection and placement

Designing for fauna

Designing for maintenanceTo ensure the project is resilient to current and future pressures and the investment in the rehabilitation is realised, interventions need to be designed and constructed to allow for future maintenance, considering the frequency, duration, access and cost. An example is the design of small curb-side litter traps (openings in road curbs that allow sediment and debris to collect, minimising the blockages of gutters and lowering the amount of possibly contaminated sediment entering rivers through the stormwater system). To trap sediment and debris they need to have a rough surface with an uneven bed and protruding rocks. However, this design means that maintenance crews cannot get shovels in efficiently to remove the accumulated litter. The result is that the structure could quickly become ineffective. A repositioning of the rough area so that maintenance can occur would make the initial design more effective. Grass swales can act as water quality improvement systems. However, they can become boggy and difficult to access and maintain if they are not constructed with vehicle access in mind. Weed management interventions need to consider long-term maintenance. Many weed management activities can result in short-term ecosystem improvement but without maintenance can revert to previous conditions. Weed management needs to consider the broader catchment and landscape. Interventions can require ongoing maintenance, or get to a point where they are self-sustaining[1]. The former are often engineered, while the latter are frequently vegetation driven solutions. The maintenance frequency can be categorised into the following three types[1]:

Routine maintenance can often be more efficient than irregular checks. For example, invasive weeds can regrow and establish quickly. Where fencing has been installed, routine maintenance is essential to ensure fauna such as turtles are not trapped, or that the effects of feral pests such as pigs do not get worse if they can get inside the fence. Monitoring designWhen planning for the rehabilitation of aquatic ecosystems, it is important to make decisions based on the best available knowledge at several scales. Scale can be spatial (i.e. site, catchment, and broader system-scales) and temporal (i.e. specific climatic seasons and the suitability of rehabilitation during these times). The services provided by a system are dependent on the condition of the system. Undertaking and documenting the condition of the site (such as WetCAT for lacustrine and palustrine) provides the basis for a monitoring program which will assess the effectiveness of the management intervention and can be used for evaluation and adaptation. A condition assessment should have been done as part of step 2 to establish the baseline before any intervention has occurred. A Condition Assessment Monitoring Plan (CAMP) should be developed as part of step 5. The CAMP is a foundational process that documents the present condition and expected changes for indicators. Importantly, it also serves as a record to inform others who may not have been involved in the design of the project or its assessment/monitoring approach. The CAMP can be built from existing documents, such as funding applications and project plans. Information that is already available in the funding application, project plan, Aquatic Ecosystem Rehabilitation Plans (AERP) or similar planning documents can be referenced, rather than re-writing, for the purposes of the CAMP. The purpose of the CAMP is to record the logic and reasoning for the assessment/monitoring of changes in the condition in a wetland after an event or resulting from management interventions. The CAMP sets out the decisions, the reasoning (rationale) behind those decisions, and what changes are expected against each of the selected indicators. A suggested outline for the CAMP is as follows:

Having a CAMP, allows for an assessment of both the immediate response to project intervention and long-term trends of condition indicators during and following intervention and event recovery. An important aspect of the CAMP is that it distinguishes the expected change in condition due to management intervention within the context of background variability (i.e., threats in the wetland surrounding area and at the landscape scale as well as background variability from weather, biological and chemical processes). A CAMP should document the frequency and timing of monitoring and the site location. Costing and review of the design planThe final design needs to be properly costed and care must be taken to ensure that the costing is for the life of the project, including any long-term objectives. Costings need to include site monitoring and maintenance as well as ongoing stakeholder communication and information sharing. In cases where there are multiple intervention options the detailed design enables them to be compared based on variables such as cost, the amount of disturbance at the site, or the greatest community support. A final review of the design plan allows for refinement based on the funds available and the timing of actions. This may result in an amendment of the interventions used or staging of the project.

Things to think about

Two simple example action lists can be seen by clicking on the thumbnails below. Additional information

References

Last updated: 30 June 2022 This page should be cited as: Department of Environment, Science and Innovation, Queensland (2022) Step 5: Produce detailed design, WetlandInfo website, accessed 8 May 2025. Available at: https://wetlandinfo.des.qld.gov.au/wetlands/management/rehabilitation/rehab-process/step-5.html |

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation