|

|

Aquatic fauna passage (biopassage)Many Australian native fish species and other water-based fauna need a range of habitats to complete their life cycle and rely on specific seasonal and life stage habitats. Fauna often need passage between different habitats, e.g. to move upstream and downstream, for several critical reasons, such as to:

This page and following pages provide general information about aquatic fauna passage, types of movement and ways to facilitate improved aquatic fauna passage. Quick facts

Disclaimer: In addition to the standard disclaimer located at the bottom of the page, please note the content presented is based on current knowledge of biopassage designs. Many of the biopassage systems described have not been trialled in all regions in Queensland. Please note that biopassage systems (fishways) built prior to 2014 were built differently to current standards. Information on these pages may be updated when possible as new trials are conducted, effectiveness is monitored and research is undertaken. To submit further information on biopassage designs or suggestions for additional technologies, please contact us using the feedback link at the bottom of this page. A range of legislation and approvals may be required for construction, particularly under the Fisheries Act 1994 and Planning Act 2016. Many of the tools and much of the knowledge and information about fishway types were sourced from, and developed within, Queensland Fisheries. Contact local and State government at the beginning of any project before any construction or planning is undertaken to ensure appropriate requirements are incorporated into the project.

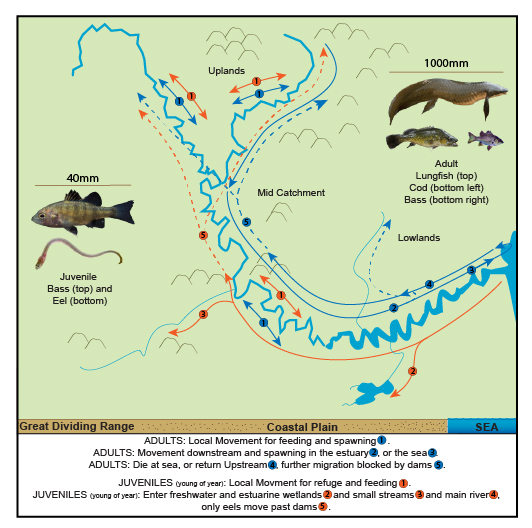

Aquatic fauna passage (biopassage) is the process where fish and other water based fauna move naturally around their environment (modified from Obstructions to fish passage in New South Wales South Coast streams[3]). Biopassage is critical to the survival of many native species. Species of both fresh and saltwater fish, for example, need to move freely within waters at different times to access food and shelter, to avoid predators, and to seek out mates to breed and reproduce. Examples of the various types and reasons movement are included in movement types below. Biopassage may be maintained or improved via the retention or restoration of waterway and aquatic connectivity and conditions, to facilitate the passage of all mobile aquatic species throughout their life cycle[5]. Biopassage, including fish passage and turtle passage, can be improved through structures such as fishways, fish ladders, fish-friendly culverts, elver passes or eel passes and through turtleways[4]. Turtleways, elver/eel and other aquatic fauna passes are considered emerging technologies. For the purposes of these webpages, fish, aquatic fauna and aquatic species are used interchangeably. Aquatic fauna can rely on access to a wide range of habitats for survival during their life cycle. Appropriate connectivity between habitats facilitates these life history events and supports populations of aquatic fauna to thrive, and drives migration. Movement typesFish and other aquatic species are stimulated to move by a variety of cues, including changes to the season or changes to water flow. Aquatic species move through waterways during times of flow to repopulate areas after dry periods or drought, resulting in genetic variability between streams. In dryland river systems, where flow ceases for extended periods, aquatic species become reliant on deeper pools or waterholes as refuges. Access to these refuge areas is critical for the survival of aquatic species through dry periods. After dry events, biopassage is critical for repopulation of the system. Aquatic species move in many ways, such as:

Some aquatic species migrate between fresh and salt water to complete their life cycle[1]. This migration is termed diadromy and there are three categories of diadromous species - catadromous, anadromous, and amphidromous See the Movement page for more information. Additional information

Pages under this sectionReferences

Last updated: 10 May 2021 This page should be cited as: Department of Environment, Science and Innovation, Queensland (2021) Aquatic fauna passage (biopassage), WetlandInfo website, accessed 8 May 2025. Available at: https://wetlandinfo.des.qld.gov.au/wetlands/management/fish-passage/ |

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation