|

|

Quick facts

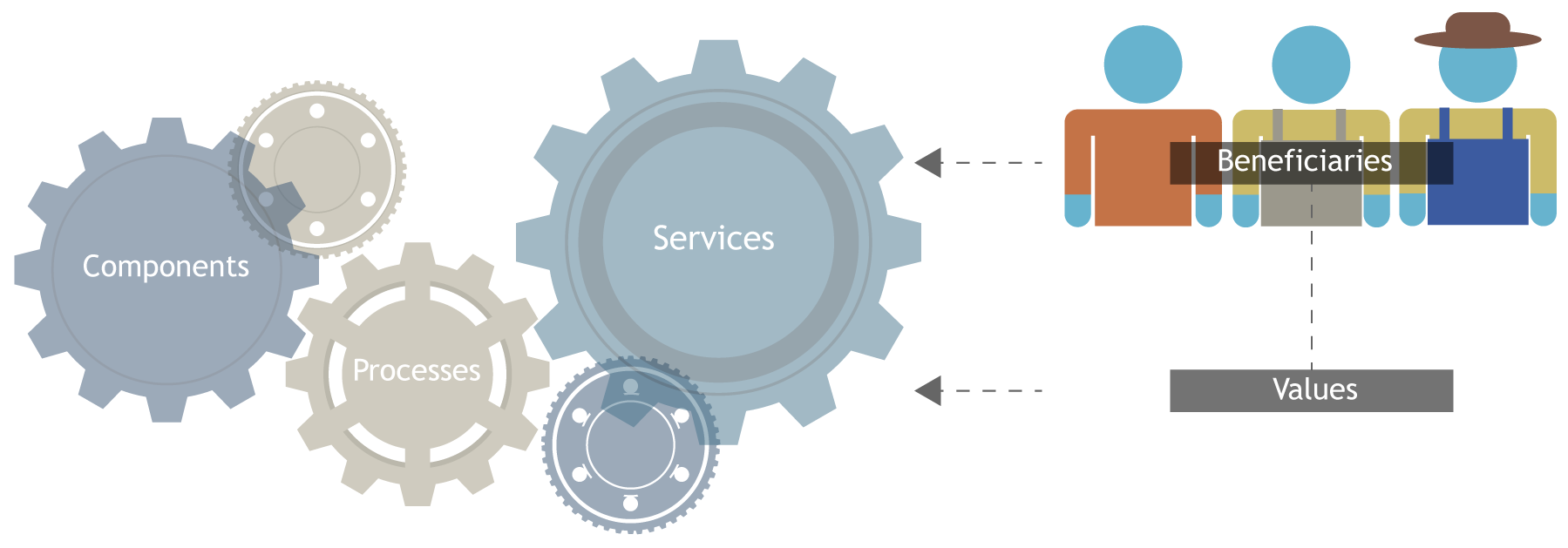

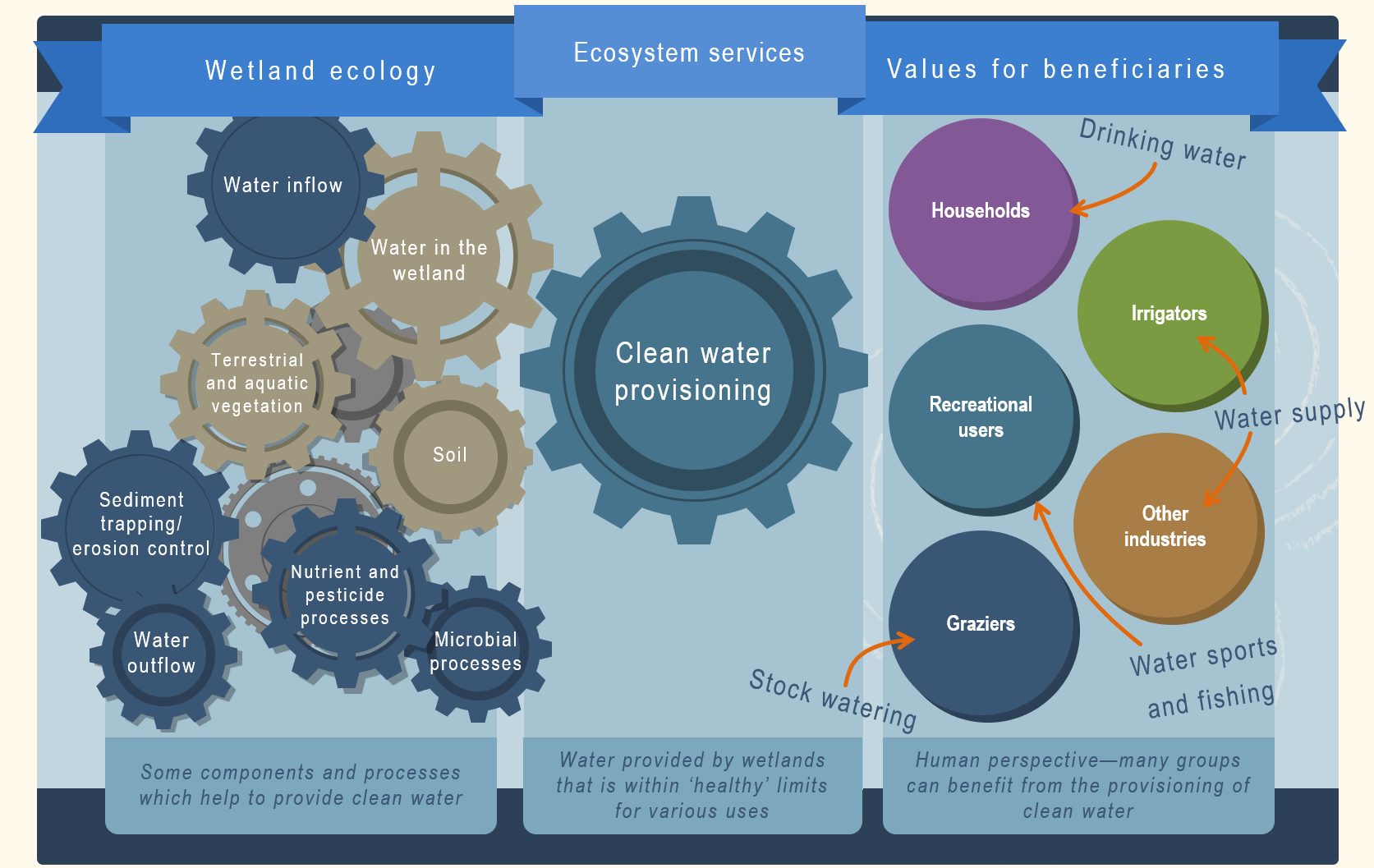

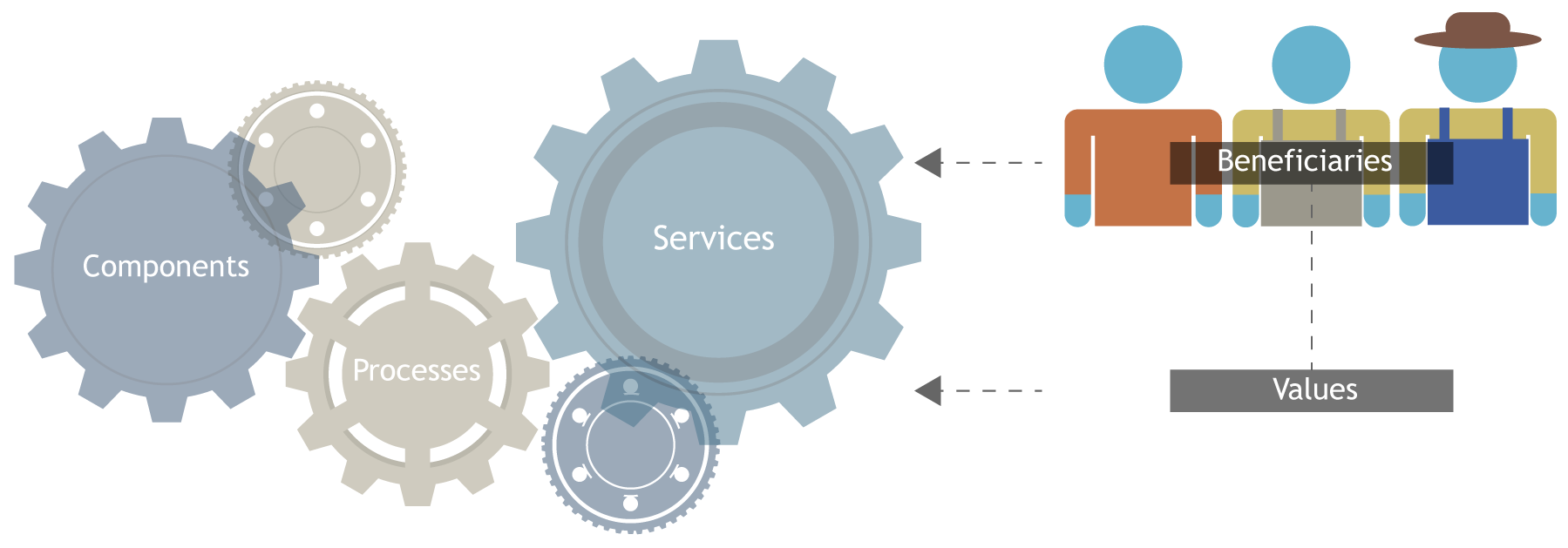

- The key

-

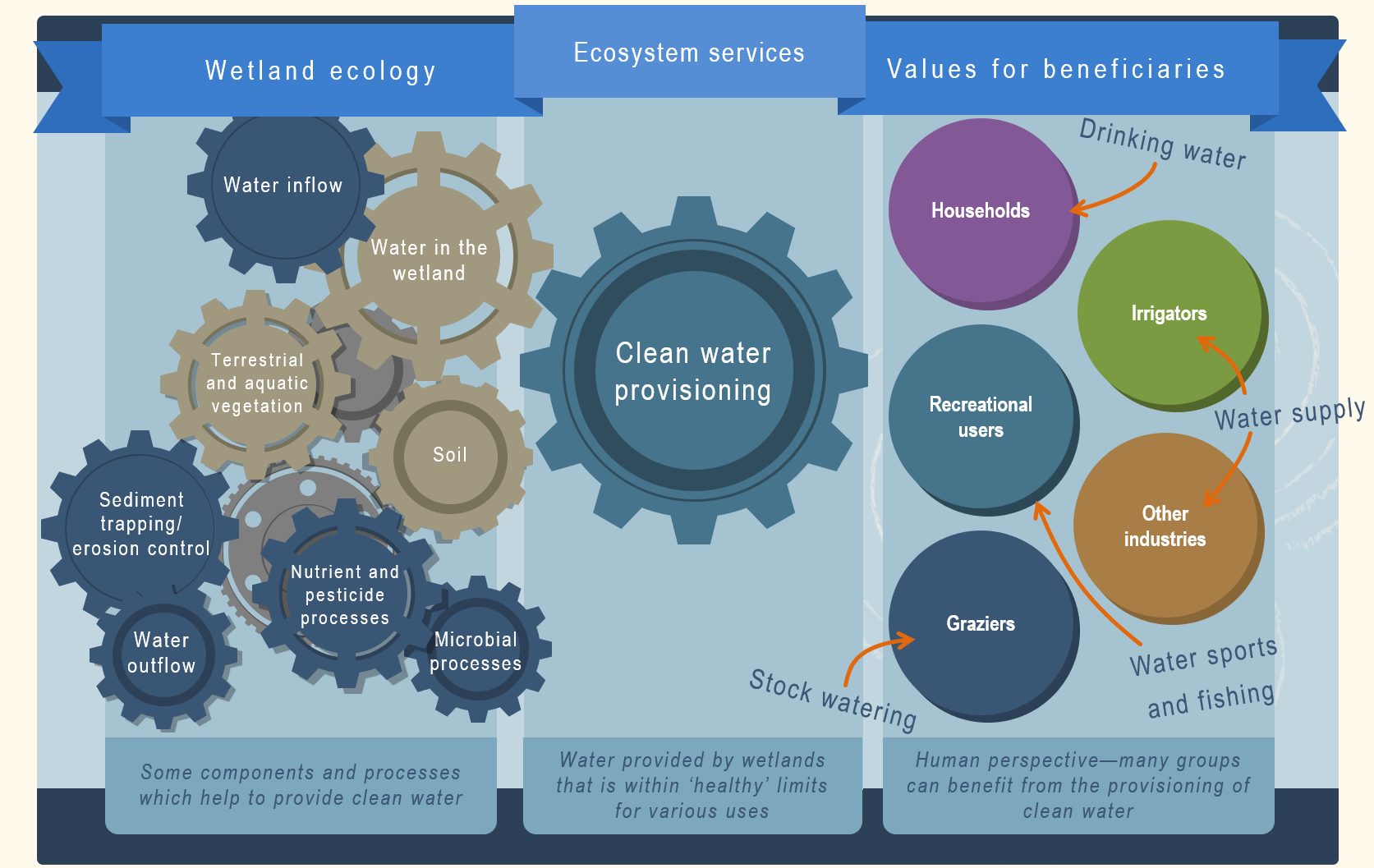

to defining a service is through identifying the different ways in which humans use and benefit from the resource[14][8]. Different beneficiaries value services in different ways.

Who are beneficiaries and stakeholders?

Beneficiaries are the people who benefit from the services provided by an ecosystem.

Stakeholders are those who are directly impacted by and/or influence decision-making[5].

Not all stakeholders will be positively impacted by a service, and thus, not all stakeholders are beneficiaries of an ecosystem. For example, a project preserving a habitat for existence or bequest value (e.g. the benefit a beneficiary receives from preserving a habitat for future generations) may positively impact the beneficiaries who value a habitat for those reasons, while a stakeholder (e.g. land manager) who relies on the material benefits that ecosystem provides (e.g. the agricultural products that are able to be grown on that land) may be negatively impacted.

How to identify beneficiaries and stakeholders?

Stakeholders and beneficiaries can be identified from the roles that individuals play in the community (e.g. a local marine advisory group may represent recreational fishers, conservation groups, and other stakeholder interested in a local aquatic ecosystem) or that arise from their interests (e.g. a recreational angling group)[12]. Understanding how local people impacted by a decision identify themselves (e.g. as a beneficiary, stakeholder, or both) will help decisionmakers ensure that the right people are engaged in decision-making so that the decisions are appropriate and any trade-offs or conflict can be identified and mitigated[12].

Because services contribute (either directly or indirectly) to human well-being, beneficiaries can be categorised into overarching groups that closely align with services[2][3].

| Overarching beneficiary/stakeholder categories (adapted from FEGS and NESCS Plus[8]) |

| |

|

|

Agricultural Users (e.g. irrigators, farmers)

|

Commercial/Industrial users (e.g. extractors) |

|

Financial providers

|

Commercial/Military Transport users (e.g. transporters of goods) |

|

Government, Municipal, Residential users (e.g. drinking water plant operators)

|

Recreational users (e.g. experiencers, hunters) |

|

Subsistence users (e.g. water subsisters)

|

Learning users (e.g. educators, students) |

|

Inspirational users (e.g. spiritual and ceremonial participants)

|

Humanity (e.g. all humans) |

| Non-use (e.g. people who care) |

Earth as a living entity |

Beneficiaries can be located within, close to, or far away from the wetland and may or may not be aware of the benefits they are receiving (adapted from Plant et al, 2012[10]). The distance of a beneficiary from an ecosystem often influences how connected a beneficiary is to a service or benefit. Some climate mitigation services or other non-use values (e.g. people who care about the Great Barrier Reef and its continued existence), can have benefits that are not spatially-linked to the beneficiary receiving them[2].

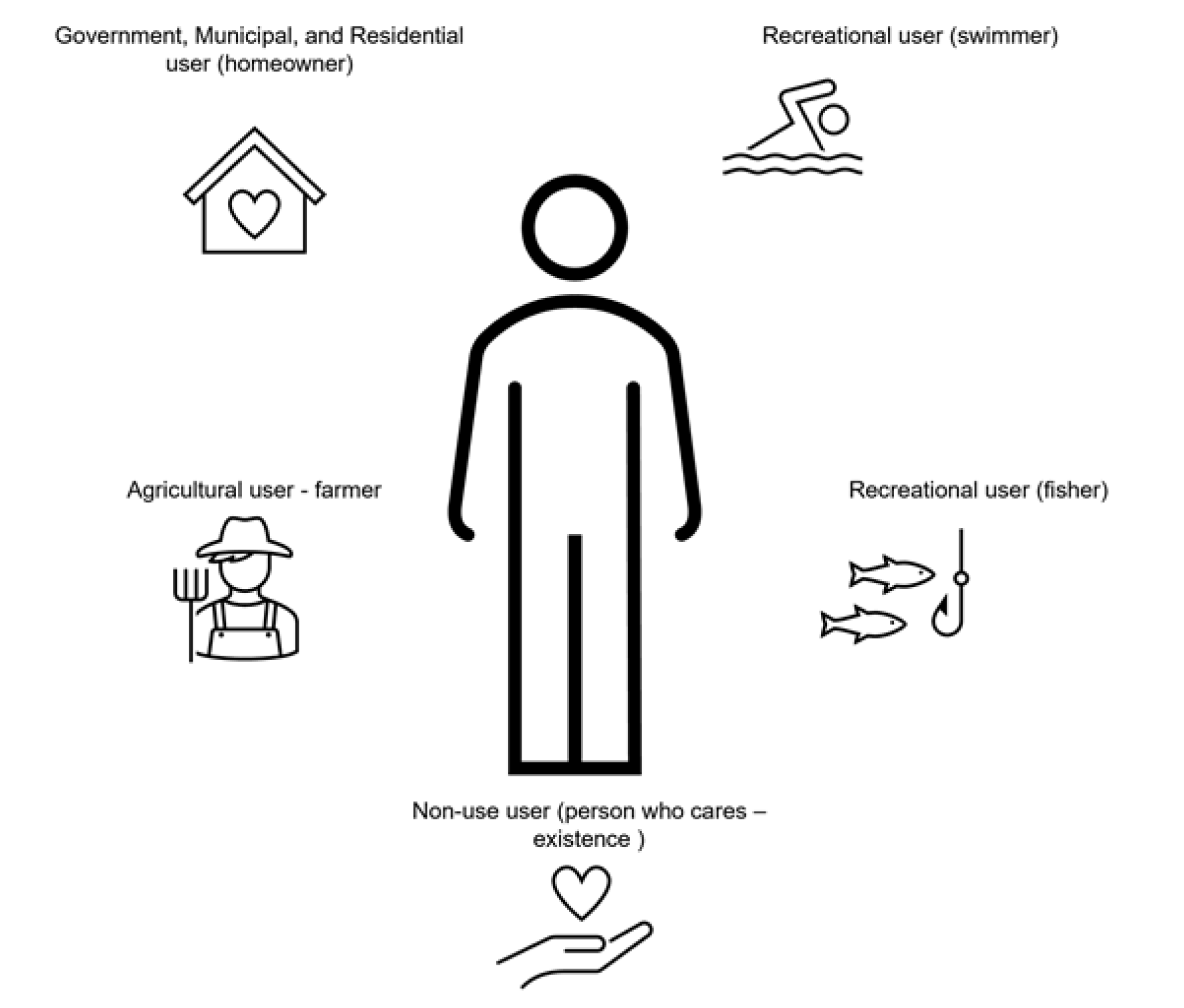

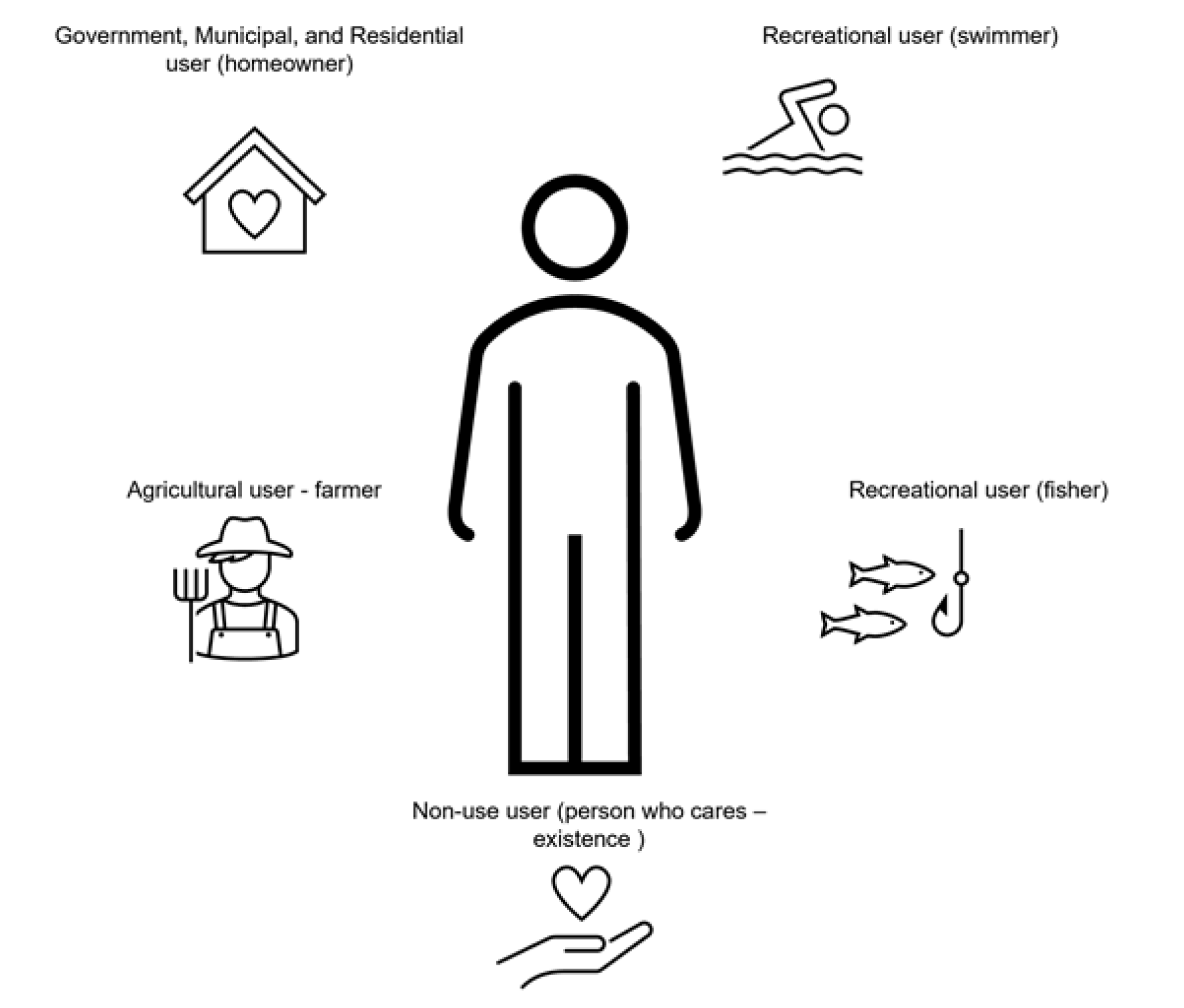

A single beneficiary or stakeholder may have multiple interests and can be represented in more than one beneficiary/stakeholder category or subcategory[14]. For example, an individual beneficiary who owns land on or near a wetland may appreciate the aesthetic views of the wetland, the water it provides for irrigation, and the recreational values it provides for fishing or swimming.

An example illustrating how a single beneficiary of a wetland (e.g. lacustrine wetland) may fall under multiple beneficiary categories and/or subcategories. Adapted from Landers and Nahlik (2013) [7].

Why identify beneficiaries and stakeholders?

Knowing who the beneficiaries are for an ecosystem helps decision-makers make decisions based on what matters to who and what components/processes/services provided by an ecosystem are directly valued by beneficiaries[12]. For example, when prioritising and/or rehabilitating/restoring aquatic ecosystems, identifying and involving beneficiaries ensures that the objectives of the project and resulting management actions are aligned with beneficiaries’ wants and needs[9][4][5]. Beneficiaries and stakeholders should be identified early on in the planning process to ensure that outcomes are appropriate (e.g. at the correct scale, engage the correct people).

Beneficiaries and stakeholders are integral to the Whole-of-System, Values-Based Framework and beneficiaries value services in many ways, including economically and through other non-use values that cannot be monetised, such as existence values.

Viewing services from the beneficiary perspective recognises the relationship between humans and nature and ensures that management considers both the goods and services that nature provides and the social context of environmental issues[6].

It is important to note that beneficiaries may hold differing values based on their interests and conflict may arise between different beneficiary groups and values[1].

How do beneficiaries relate to the environment?

An ecosystem may have several different beneficiaries who appreciate the same ecosystem for different services and values. For instance, some beneficiaries may prioritise economic benefits when considering wetland rehabilitation interventions, while fishers may prioritise food and recreational benefits[11]. It is important that decision-makers identify and consider the values of these different beneficiaries when making decisions.

Pages under this section

References

- ^ Avni, N & Teschner, N (November 2019), 'Urban Waterfronts: Contemporary Streams of Planning Conflicts', Journal of Planning Literature. [online], vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 408-420. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0885412219850891 [Accessed 30 September 2021].

- ^ a b Bagstad, KJ, Villa, F, Batker, D, Harrison-Cox, J, Voigt, B & Johnson, GW (2014), 'From theoretical to actual ecosystem services: mapping beneficiaries and spatial flows in ecosystem service assessments', Ecology and Society. [online], vol. 19, no. 2, p. art64. Available at: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol19/iss2/art64/ [Accessed 28 January 2021].

- ^ Caputo, J, Beier, CM, Luzadis, VA & Groffman, PM (December 2016), 'Integrating beneficiaries into assessment of ecosystem services from managed forests at the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, USA', Forest Ecosystems. [online], vol. 3, no. 1, p. 13. Available at: https://forestecosyst.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40663-016-0072-9 [Accessed 30 September 2021].

- ^ Conservation Measures Partnership (2020), Open Standards for the Practice of Conservation. [online], p. 81, Conservation Measures Partnership. Available at: https://conservationstandards.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2020/10/CMP-Open-Standards-for-the-Practice-of-Conservation-v4.0.pdf.

- ^ a b Department of Environment and Science (2020), Stakeholder Engagement Framework. [online], p. 24, Department of Environment and Science, Brisbane, Queensland. Available at: https://desintranet.govnet.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/331624/stakeholder-engagement-framework.pdf.

- ^ a b DeWitt, TH, Berry, WJ, Canfield, TJ, Fulford, RS, Harwell, MC, Hoffman, JC, Johnston, JM, Newcomer-Johnson, TA, Ringold, PL, Russell, MJ, Sharpe, LA & Yee, SH (2020), 'The Final Ecosystem Goods & Services (FEGS) Approach: A Beneficiary-Centric Method to Support Ecosystem-Based Management', in T G O’Higgins, M Lago & T H DeWitt (eds), Ecosystem-Based Management, Ecosystem Services and Aquatic Biodiversity : Theory, Tools and Applications. [online], Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 127-145. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45843-0_7.

- ^ Landers, DH & Nahlik, AM (2013), Final ecosystem goods and services classification system (FEGS-CS). [online], vol. EPA/600/R-13/ORD-004914., United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/final-ecosystem-goods-and-services-fegs [Accessed 22 September 2020].

- ^ a b Newcomer-Johnson, T, Andrews, F, Corona, J, DeWitt, TH, Harwell, MC, Rhodes, C, Ringold, P, Russell, MJ & Van Houtven, G (2020), National Ecosystem Services Classification System (NESCS) Plus. [online], vol. EPA/600/R20/267, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Available at: https://cfpub.epa.gov/si/si_public_record_Report.cfm?dirEntryId=350613&Lab=CEMM.

- ^ O’Connor, S & Kenter, JO (September 2019), 'Making intrinsic values work; integrating intrinsic values of the more-than-human world through the Life Framework of Values', Sustainability Science. [online], vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 1247-1265. Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11625-019-00715-7 [Accessed 24 March 2021].

- ^ Plant, R, Taylor, C, Hamstead, M & Prior, T (2012), Recognising the broader benefits of aquatic systems in water planning: an ecosystem services approach. Waterlines report, National Water Commission, Canberra, ACT.

- ^ Scholte, SSK, Todorova, M, van Teeffelen, AJA & Verburg, PH (June 2016), 'Public Support for Wetland Restoration: What is the Link With Ecosystem Service Values?', Wetlands. [online], vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 467-481. Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s13157-016-0755-6 [Accessed 9 February 2021].

- ^ a b c Sharpe, LM, Hernandez, CL & Jackson, CA (2020), 'Prioritizing Stakeholders, Beneficiaries, and Environmental Attributes: A Tool for Ecosystem-Based Management', in T G O’Higgins, M Lago & T H DeWitt (eds), Ecosystem-Based Management, Ecosystem Services and Aquatic Biodiversity. [online], Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 189-211. Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-45843-0_10 [Accessed 16 December 2021].

- ^ Tett, P, Gowen, R, Painting, S, Elliott, M, Forster, R, Mills, D, Bresnan, E, Capuzzo, E, Fernandes, T, Foden, J, Geider, R, Gilpin, L, Huxham, M, McQuatters-Gollop, A, Malcolm, S, Saux-Picart, S, Platt, T, Racault, M, Sathyendranath, S, van der Molen, J & Wilkinson, M (4 December 2013), 'Framework for understanding marine ecosystem health', Marine Ecology Progress Series. [online], vol. 494, pp. 1-27. Available at: http://www.int-res.com/abstracts/meps/v494/p1-27/ [Accessed 22 June 2021].

- ^ a b US Environmental Protection Agency (2015), National Ecosystem Services Classification System (NESCS): Framework Design and Policy Application. [online], vol. PA/800/R-15/002, US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington DC, U.S.A.. Available at: https://cfpub.epa.gov/si/si_public_record_report.cfm?dirEntryId=310592&Lab=NHEERL.

Last updated: 14 November 2022

This page should be cited as:

Department of Environment, Science and Innovation, Queensland (2022) Beneficiaries and stakeholders, WetlandInfo website, accessed 8 May 2025. Available at: https://wetlandinfo.des.qld.gov.au/wetlands/management/wetland-values/beneficiaries/

|

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation