|

|

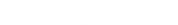

Systems (components and processes)Understanding the parts of an aquatic ecosystem (components), how it works (processes), how it integrates with the local social/ecological landscape, and the services it provides is critical to determining appropriate management interventions. This is also informed by understanding the condition of the system. Quick facts

Things to think about

Understanding how rivers work (riverine components and processes)Rivers convey water in a channel, and in addition to the water, the river channel and its surrounding riparian areas are essential ecosystems, supporting fish and other species. The flow in the channel is not just a flow of water, but also of sediment, chemicals (including nutrients) and biota. Sediment can be moved along the bed (bed load) or in suspension in the water column (suspended and wash loads). Dissolved chemicals can also be transported through the river system. Some rivers flow to the coast, often connecting to estuarine systems, while others are endorheic or internally draining, with the channel ending in a salt lake or flat (Bulloo, Lake Eyre). Water in river channels may be lost to groundwater, while other channels may gain water from groundwater as well as from surface runoff. Rivers can run beside or through hills or can be located in relatively flat floodplains. The river may cause erosion on the outside of bends, and deposition inside, causing the channel to migrate laterally across the floodplain. Sediment (usually finer material) can also be deposited on the floodplain when the channel overflows (overbank flows) meaning that the floodplain builds up vertically (aggrades). There may be a single channel or multiple channels in a floodplain, and some channels can move to new positions on the floodplain (avulse)[2]. Vegetation and other components such as clays and rocks on the floodplain help to control the rate of lateral migration and overbank deposition and these components can also influence the velocity of flow when present in the channel. The condition of the system effects how the system works and can be understood using an appropriate condition assessment tool. In Great Barrier Reef Catchments the Gully and Streambank Toolbox can be used to assess erosion potential and sediment loss. Understanding how intertidal and subtidal systems work (estuarine and marine components and processes)Intertidal and subtidal ecosystems may be composed of both estuarine systems and marine systems[1][3]. Subtidal ecosystems (e.g. mangroves or saltmarsh and muddy and sandy substrate) are permanently below the level of low tide, (i.e. continuously submerged), whereas intertidal ecosystems are found between the high tide and low tide, experiencing fluctuating influences of land and sea[4]. The tidal waters inundating intertidal and subtidal habitats can be fresh, brackish, saline (usually oceanic) or even more saline than oceanic waters (hypersaline). Intertidal ecosystems are a dynamic complex of plant, animal and micro-organism communities and their non-living environment, that interact as a functioning unit. Subtidal and intertidal ecosystems are influenced by a range of physical, chemical and biological variables that fluctuate and cycle at various scales across time and space. The condition of the system effects how the system works and can be understood using an appropriate condition assessment tool. Understanding how lacustrine systems work (lacustrine components and processes)Lacustrine wetlands (lakes) are dominated by open water. They are largely non-vegetated, non-channel systems and are not influenced by tidal waters. They include lakes, farm dams, reservoirs, and many other modified and highly modified systems. They often have a surrounding riparian or transitional fringe of trees. They are usually relatively deep and provide habitat and breeding areas for a wide variety of species. Lakes in Queensland, particularly in arid and semi-arid areas, are highly variable. Some are known to dry out and to support species adapted to these large variations in water availability, while others stay wet for long periods and provide a refuge during dry times. The condition of the system effects how the system works and can be understood using an appropriate condition assessment tool. For a definition of lacustrine wetland systems see the Wetland systems page Understanding how palustrine systems work (palustrine components and processes)Palustrine wetlands are what many people traditionally think of as a wetland—they are vegetated, non-channel systems that are not influenced significantly by tidal waters. They have over 30% emergent vegetation cover, including trees, shrubs, grasses and sedges. Palustrine wetlands include billabongs, swamps, bogs, springs, and soaks. They can occur in both floodplain and non-floodplain landscapes and can be ephemeral, seasonally or permanently inundated. Palustrine wetlands are usually shallow (less than 2 m deep). These wetlands provide habitat and breeding areas for a wide variety of species. The condition of the system effects how the system works and can be understood using an appropriate condition assessment tool. For a definition of palustrine wetland systems see the Wetland systems page References

Last updated: 30 June 2022 This page should be cited as: Department of Environment, Science and Innovation, Queensland (2022) Systems (components and processes), WetlandInfo website, accessed 8 May 2025. Available at: https://wetlandinfo.des.qld.gov.au/wetlands/management/rehabilitation/rehab-process/step-2/wetland-system/ |

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation

— Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation